One of the nine canonical lyric poets of Ancient Greece, Sappho remains something of a chimera to poets and classicists. No copies of the nine books of poetry she produced while living on the island of Lesbos around 600BC have survived – variously lost in the destruction of the Library of Alexandria, burned (as some Renaissance scholars believed) in a purge by Pope Gregory VII or otherwise destroyed – leaving only a few complete poems and a handful of tantalising fragments. Until the discovery of a further collection of papyrus fragments in the early 20th century, most of her poetry was known to us only so far as it was quoted in other works. Bliss Carman’s One Hundred Lyrics represents the first attempt to imaginatively expand this fragmentary verse into full poems.

Cataloguing by Sammy Jay

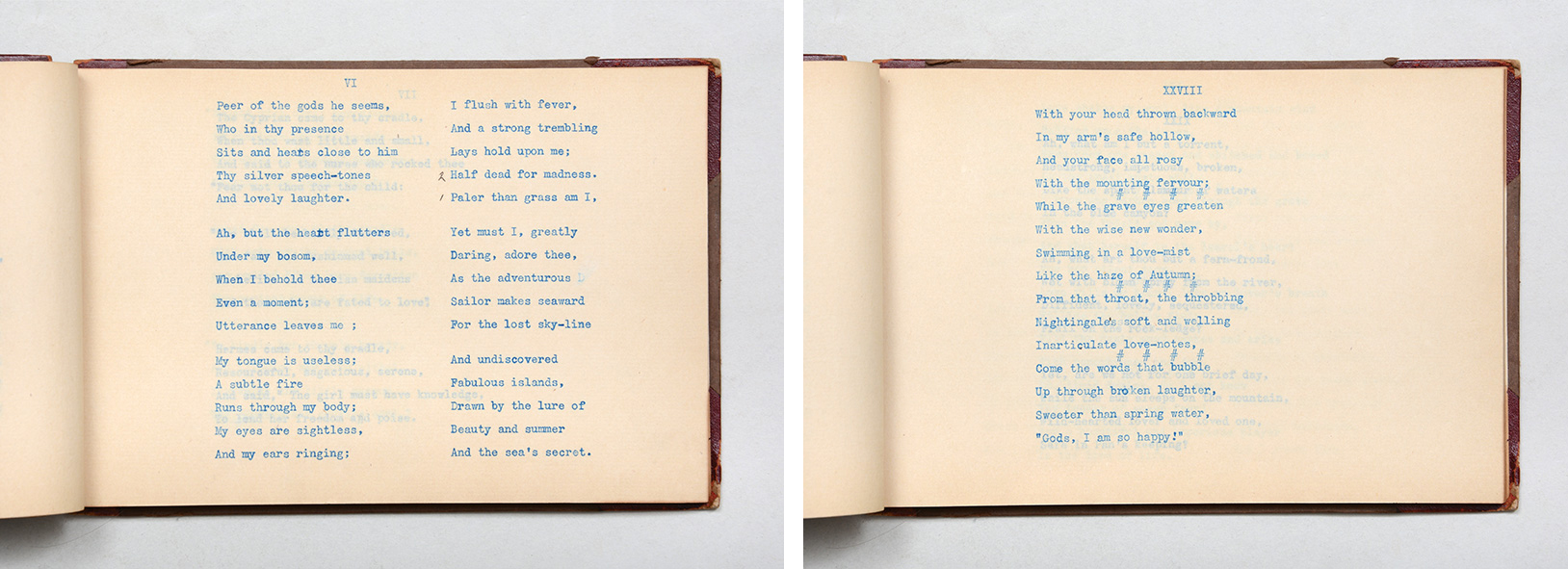

Pre-publication hand-corrected typescript of Canada’s unofficial poet laureate Bliss Carman’s magnum opus, the first comprehensive and fully imagined rendering into English of the thithero fragmentary poems of Sappho, the greatest surviving lyric poet of the ancient world.

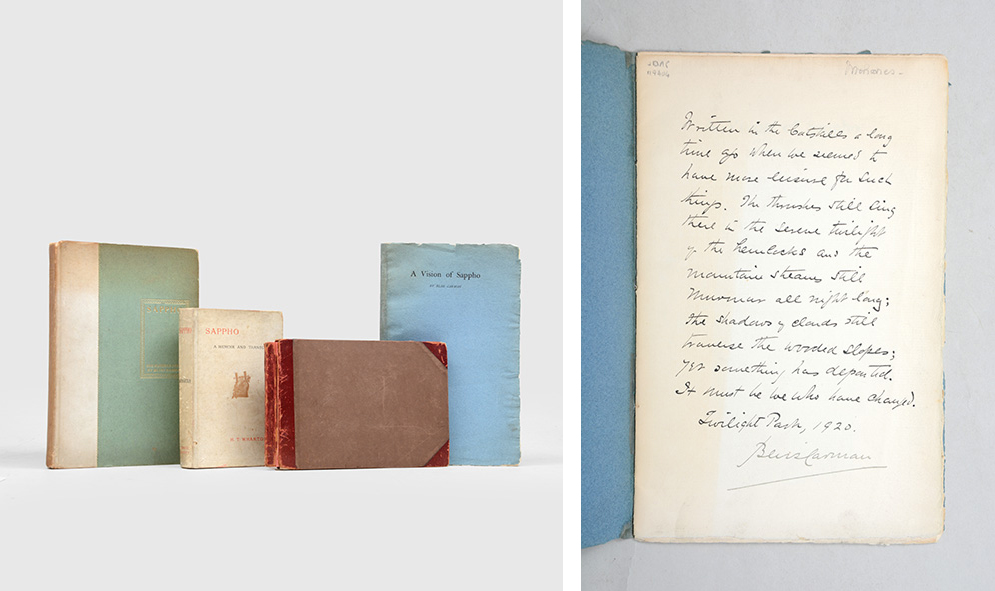

This is presented together with a very scarce copy of the first edition, printed October 1903 and published 1904 in Boston by L. C. Page in a limited edition of 500 numbered copies (of which this is copy 13), an inscribed copy of the rare privately printed Carman poem A Vision of Sappho, and a rare US issue of the scarce first edition of the book from which Carman worked to create his lyrics, H. T. Wharton’s scholarly compendium of the surviving Greek fragments together with the previous attempts at English translations (London: David Stott, 1875, with here a cancel title page for the US issue by Jansen, McClurg, and Co. of Chicago).

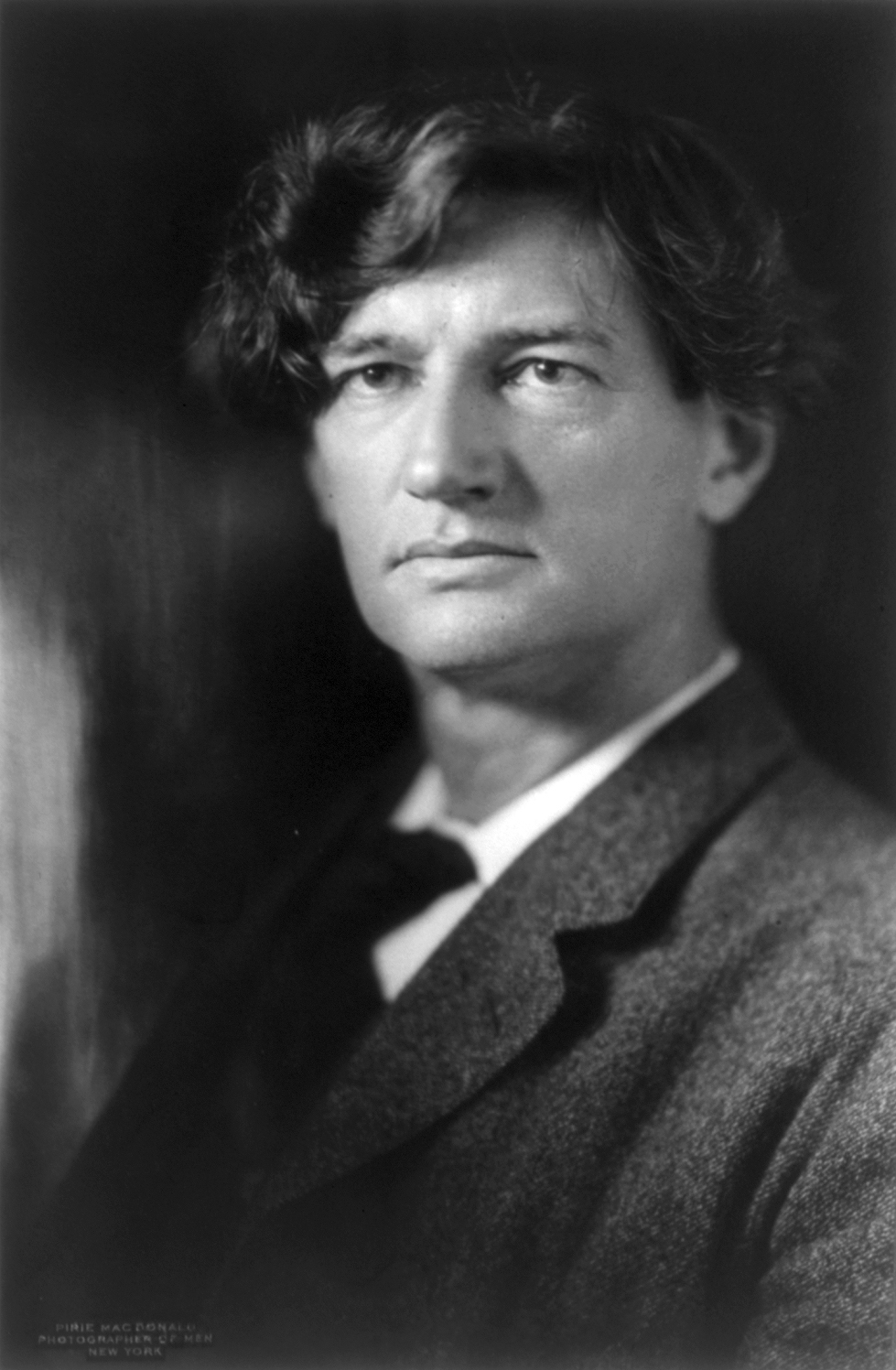

![Pirie MacDonald [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.peterharrington.co.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Bliss_Carman_cph.3b15835.jpg)

Bliss Carman

The first appearance of Carman’s Sappho lyrics was a private printing (60 copies) of only 15 lyrics. The omission of that item here must be excused by its extreme rarity – the last copy recorded at auction was in 1926. Carman continued work on swelling the number of the Sappho lyrics, and also wrote his own long original poem evoking the imaginative excitement of this encounter with Sappho, entitled A Vision of Sappho. This was printed in December 1903 again in a private edition of 60 copies. The copy included here (as rare as the 15 Sappho lyrics of 1902 – the last copy of A Vision of Sappho at auction was in 1938) has been reminiscently inscribed by Carman on the first blank: “Written in the Catskills a long time ago when we seemed to have more leisure for such things. The thrushes still sing there in the serene twilight to the hemlocks and the mountains streams still murmur all night long; the shadows of clouds still traverse the wooded slopes; yet something has departed. It must be we who have changed. Twilight Park, 1920. Bliss Carman”.

Carman’s One Hundred Lyrics of Sappho would come to be his most enduring work – acknowledged by the Dictionary of Canadian Biography to be his “finest volume of poetry”. It is particularly notable for having made Sappho accessible and exciting to a non-academic English-speaking audience, and some lyrics, such as “I loved thee, Atthis, in the long ago” and “Over the roofs the honey-coloured moon”, are still quoted by Carman and Sappho enthusiasts alike. It was read and admired in particular by modernist poets such as Wallace Stephens and Ezra Pound. Indeed, critic D. M. R. Bentley has suggested that “the brief, crisp lyrics of the Sappho volume almost certainly contributed to the aesthetic and practice of Imagism”.

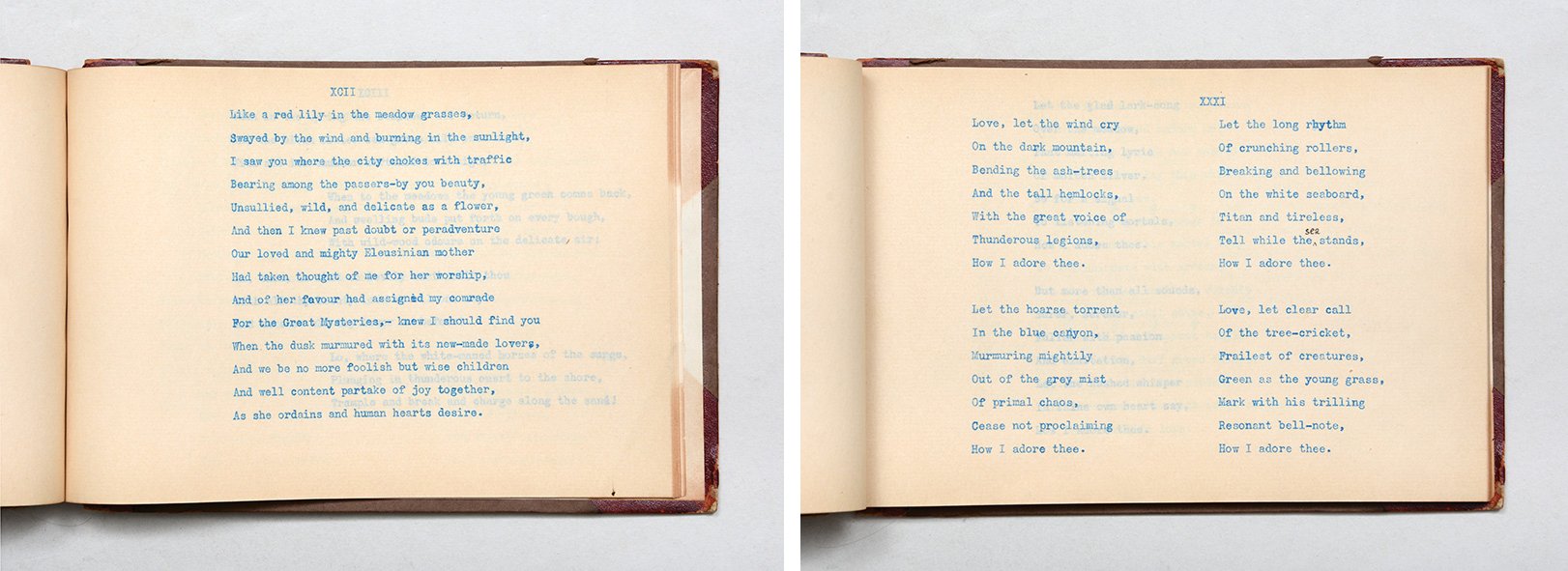

The typescript here is the linchpin of this presentation of the Carman/Sappho story. Textually it stands between the typescript in the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library, and the published version. The prior typescript had more lyrics, and was numbered in accordance to Wharton’s numbering of the fragments that inspired them. Several of those Carman cut, and the present typescript has been renumbered and rearranged into its near-published state. A previous owner has enumerated, on a lengthy hand-list, the textual differences between the lyrics in this typescript and those in the Berg. This document also carries the assertion that various letter forms in the manuscript corrections here tally satisfactorily with “Carman’s hand in letters to Miss Hawthorne in the Berg MS”.

![By UnknownUnknown [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.peterharrington.co.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Sappho_fresco.jpg)

Woman with wax tablets and stylus (so-called “Sappho”), artist unknown

Laid in at the rear of the typescript is a near-contemporary newspaper clipping of “A Newly Discovered Poem of Sappho” translated by Joyce Kilmer (1886-1918) – an appealing continuation of the Sappho story.

View this item here. (Item sold)

If you would like to make an enquiry about selling a book, please fill out the form which can be found here.