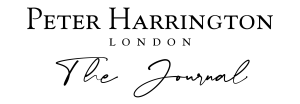

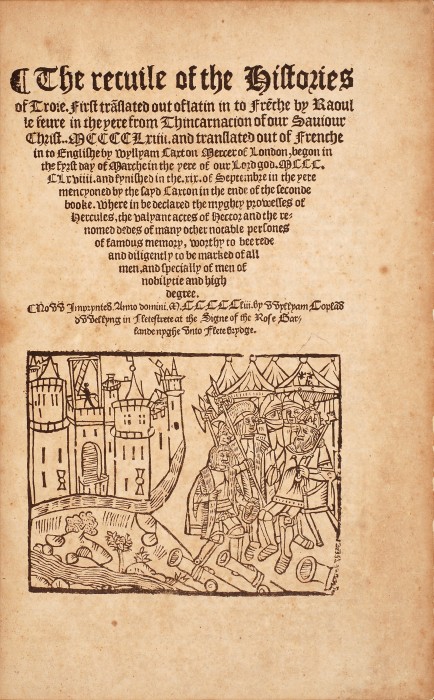

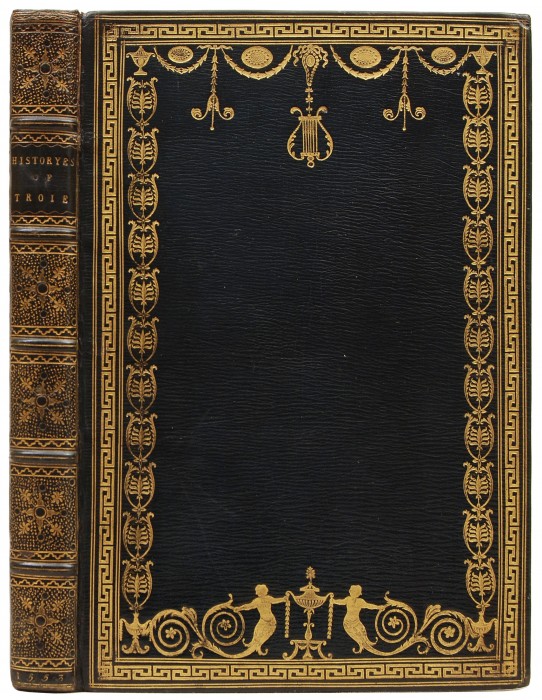

Title page of the third edition of the first book printed in English, The recuile of the Histories of Troie (1553).

Today’s post was written by Peter Harrington partner Adam Douglas, who specialises in pre-20th century literature, history, and economics.

We recently acquired a rare and splendid sixteenth-century book, The recuile of the Histories of Troie, published by William Copland in London in 1553 (book sold, 2012). The first edition of this text, published in Bruges in 1473 or 74 by William Caxton, was the very first book printed in the English language. Caxton himself is famous as the first printer in England. But why was his first English book printed in Bruges?

Philip the Good, Valois duke of Burgundy. Portrait after Roger van der Weyden c.1450

In the mid fifteenth century Bruges was the capital of high style. Ruled over by Philip the Good, Valois duke of Burgundy, whose court was the most splendid and fashionable in all of Europe, it was the centre of trade in haberdashery, cloth, and luxury wares like silks. Illuminated manuscripts with miniatures by fashionable Flemish artists were a particularly valued Burgundian export, regularly shipped in large numbers from Flanders to London.

An example of Burgundian illumination by the master Simon Marmion, whose main patron was Philip the Good.

To a prescient few, Gutenberg had sounded the death knell for the trade in illuminated manuscripts. William Caxton was a shrewd Kentish mercer, long settled in Bruges. By 1465 he had established himself as the leading English merchant there. He realised that his English customers would soon demand printed books in their own language. And so he began his English translation of a hugely popular Burgundian work, a retelling of the legend of Troy by Philip the Good’s chaplain, Raoul le Fevre.

Turbulent political times interrupted his plans. England and Burgundy plunged into a trade dispute, forcing the English merchants to leave Bruges. Caxton set aside his translation to seek an end to the trade war. Tensions eased around the time of Philip the Good’s death in 1467, and Anglo-Burgundian relations were further improved the following year when his successor, Charles the Bold, married Margaret of York, sister of Edward IV. The English king soon had reason to be grateful for the new alliance. He was deposed in 1470 and fled to Flanders under the protection of his new brother-in-law. Edward used his time there to patch up his European trade relationships, before sailing back to England in April 1471 to regain his throne.

Three months after Edward’s restoration, Caxton went to Cologne to learn the craft of printing, which had reached the city in 1464. Cologne was the Hanseatic town with the closest links to England and it had helped to settle Edward IV’s trade disputes. Here Caxton acquired a printing press, the expertise to run his own publishing business, and a German assistant, Wynken de Worde. By his own account it was during his stay in Cologne that he completed his translation of Le Fevre’s History of Troy.

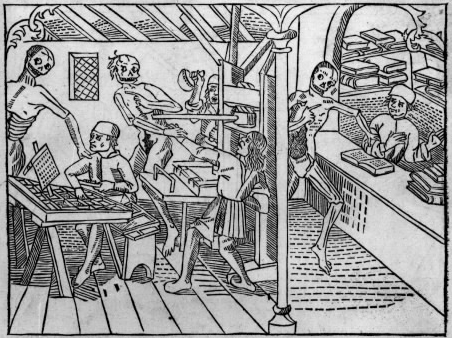

The earliest known image of a printing press, published in a Danse Macabre of 1499. Caxton would have used similar equipment in his printing business.

At the end of 1472 Caxton returned to Bruges with his new printing press ready to produce his long-gestated first work. It was a large book and took about a year to complete, being finished in late 1473 or early 1474. It was dedicated to Margaret of Burgundy, sister of the restored English king. The finished books were shipped to England for sale.

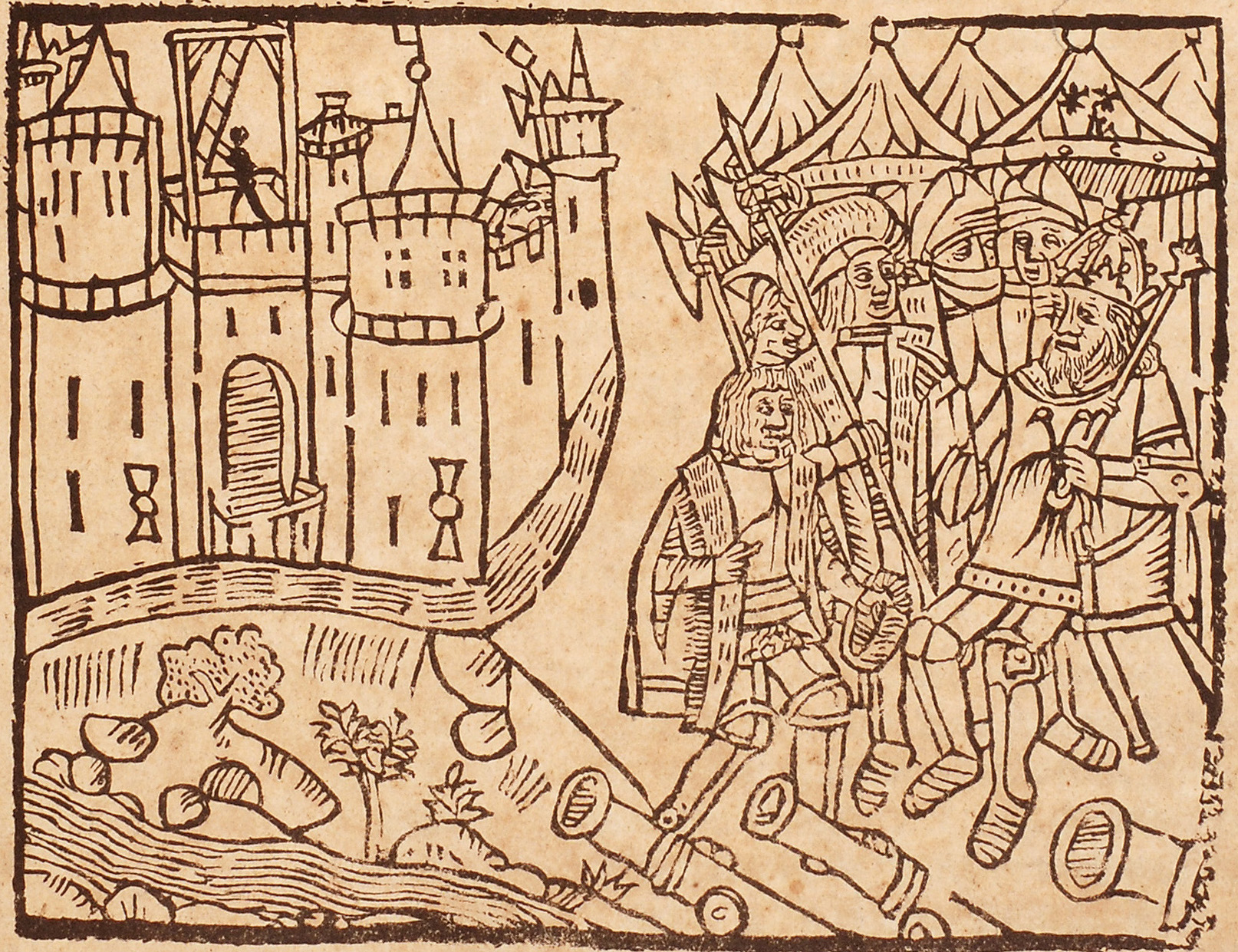

Caxton immediately printed a second English book, the Game of Chess, but his next four books were all in French. Caxton struggled to sell English books from his Bruges base.

Probably in 1476 but possibly as early as 1475, Caxton took his printing press to England, renting premises in Westminster Abbey, at the centre of court life. From now on he would print only in English and occasionally in Latin. He never printed in French again, though almost all his translations were of works written or recently printed in France or Flanders which could be marketed as new and fashionable to his English buyers.

Caxton’s device, or logo, from a book he published in London in 1489.

When Caxton died in 1492, de Worde took over his print shop and set about training a new generation of English printers. Among them was Robert Copland, who had translated French books for de Worde before turning printer himself. When Robert Copland died in 1547, a kinsman of his, William, most likely his son, took over the business. William Copland therefore represents the fourth in a direct line of succession from England’s first printer. With reprints such as this third edition of The recuile of the Histories of Troie, he provided a connection between popular reading taste of the late fifteenth century and that of the seventeenth. The eleventh edition of Caxton’s translation appeared as late as 1684, a remarkable span from Edward IV to the final year of Charles II.

Below, the sumptuous late eighteenth-century morocco binding on our 1553 copy of The recuile of the Histories of Troie:

Late eighteenth-century binding on a third edition of The recuile of the Histories of Troie printed in 1553.