Penelope and her Suitors (1912) by John William Waterhouse

The last ten years have brought particular focus to women’s engagement with the Classics. 2017 saw Emily Wilson publish her much-lauded translation of the Odyssey, and much of the press surrounding the publication focused on her status as a rare female translator of Homer’s work. She was, however, by no means the first to blaze this trail: 300 years previously, the first woman to translate Homer was a prolific but now largely forgotten scholar named Anne le Fèvre Dacier.

Dacier grew up in Saumur in the Loire region of France, where she was taught Ancient Greek and Latin by her father, Tanneguy Le Fèvre, a professor of classics. That he educated his daughter during the 17th century was unusual, and, happily, prepared her to become one of the foremost classical scholars of her day, as well as one of the most inspiring since.

Anne le Fèvre Dacier

It is a testament to her talent that Dacier’s ouvre has been held in high regard, and remained academically relevant for centuries. Even before her best-known work was published, French academic Gilles Ménage had dedicated his 1690 Historia Mulierum Philosophorum (The History of Women Philosophers) to Dacier, describing her as ‘the most learned of women, whether in the present or the past’. Touchingly, there is a school in Angers, France, where Ménage was born, named after her. Over a hundred years later, in 1803, she was again listed as one of history’s great female intellectuals by British writer Mary Hays. Hays included Dacier in her 300-entry encyclopedia of the most ‘illustrious and celebrated women’ of all time, alongside figures such as Agrippina the Elder and Queen Elizabeth I. More recently, in Harvard University Press’s The Classical Tradition, a 1,000-page volume that explores the legacy of the ancient world, Dacier is credited with popularising the classics during the Neoclassical period (particularly with women) and, through her championing of the poet, returning Homer to the literary foreground. The editors of the tome note that after Dacier’s proficient versions of the Iliad and Odyssey were published, no one else ‘dared to translate Homer for half a century’ .

But the admiration Dacier’s translations received from her male contemporaries is perhaps the best evidence of their quality. That she was considered an eminent scholar in an era that was hostile towards learned women was a considerable anomaly, so much so that she is said to have become quite the topic of conversation in Parisian salons. Her first published volume, translations of the Hellenic poet Callimachus, is what catapulted her to success. It impressed fellow academics and caught the attention of the Dauphin’s assistant tutor, Pierre Daniel-Huet, who became her patron. Huet invited Dacier to contribute to – and even co-edit – the Dauphin’s selected reading of Latin texts, Ad usum Delphini (also known as The Delphin Classics), which were subsequently read by circles beyond the royal household and helped promulgate ancient literature. Simultaneously, she had a number of Greek and Latin prose and poetry translations published independently, meaning that between 1674 and 1684, over ten of her editions were made available for purchase.

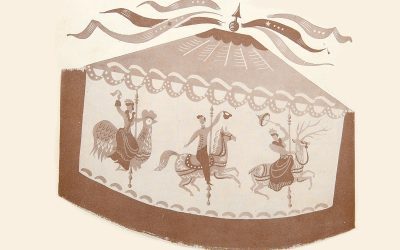

(DACIER, Anne Lefèvre, trans.) HOMER.

The Iliad. With Notes. To which are prefix’d, A large Preface, and the Life of Homer by Madam Dacier. 1712.

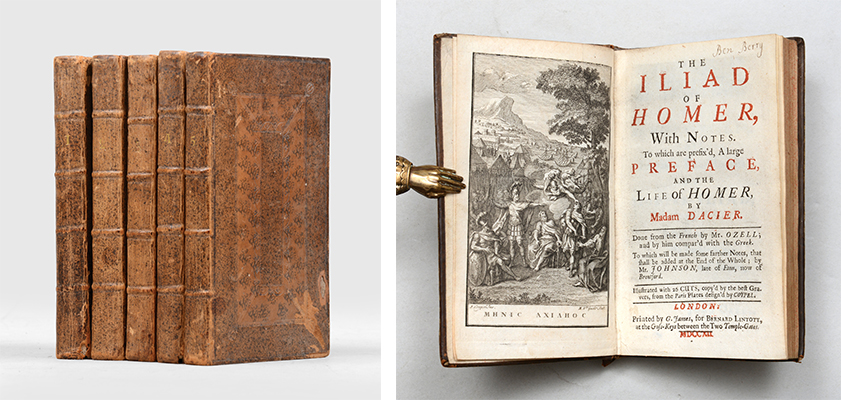

(DACIER, Anne Lefèvre, trans.) HOMER.

L’Odyséé d’Homere, traduite en françois, avec des remarques par Madame Dacier. 1716.

Then came the first of her famed translations: Homer’s epic poem the Iliad. Dacier was the first woman to tackle the dactylic hexameter poem, which was first written down in the 8th century BC. Her interpretation captures the essence of the original, with an emphasis on accurate translation over artistic license. At the same time, Dacier’s Iliad is a beautiful example of Neoclassical French prose. Her translation nine years later of the Odyssey was equally admired and was even used by Alexander Pope as a helpful reference when writing his own. Ironically, his was decried by Dacier as being unfaithful to the original.

The difference in style between Dacier and Pope’s Odysseys typified a long-standing academic debate at the time – the querelle des anciens et des modernes (the ‘ancients versus moderns’ debate). In 1714, Dacier published a treatise entitled Des Causes de la Corruption du Goût (On the Causes of the Corruption of Taste), which firmly established her position as a proponent of classical literature’s superiority. She argued that it need not be ‘improved’ and scathingly reviewed what she saw as the deterioration of aesthetic taste since ancient times. Translators such as Antoine Houdar de la Motte disagreed: what he perceived as Homer’s primitive poetic style should be updated to suit cultivated modern tastes. Dacier so opposed this view that she produced an additional two commentaries on the topic, Une Défense d’Homère (A Defence of Homer, 1715), which directly rebuffed scholars’ criticisms of the poet, and Réflexions sur la Préface de Pope (Reflections on the Preface of Pope, 1719). The latter critiqued Pope’s liberal approach to translating Homer’s Odyssey, which was a looser reproduction of the poem written in verse. ‘Whereas Pope’s translation claimed to restore Homer’s brutality, Anne Dacier saw in the poet only harmony and regularity… and in what her contemporaries found shocking, she found traces of the golden age’ (Grafton and others). This veneration of Homer is evident in the multitudinous explanatory notes that accompany her translation: for Dacier, translating the Iliad was not just an academic challenge or means for an income, it was a deeply-felt passion project.

Other female retellings of Homer have appeared in recent years. In 2011, Madeline Miller’s Song of Achilles reimagined the Trojan War from the perspective of the hero’s friend and lover, Patroclus. Just last year, Pat Barker told the story of the Trojan War in The Silence of the Girls, this time through the eyes of its female victims. What Dacier would have made of these retellings, we cannot know, but it seems apt that we should revisit her work now and celebrate her as a brilliant scholar – and, of course, as a spirited female pioneer.

By Lauren Hepburn.

If you’d like any further information on any of the books mentioned in this blog, please email us: mail@peterharrington.co.uk or call one of our booksellers on 020 7591 0220