An Interview With Collector Stacy Shirk

Could you tell us a little bit about how you first got into rare book collecting? What drew you to fairy tales as a collecting area?

Could you tell us a little bit about how you first got into rare book collecting? What drew you to fairy tales as a collecting area?

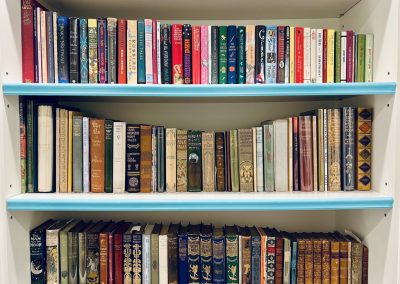

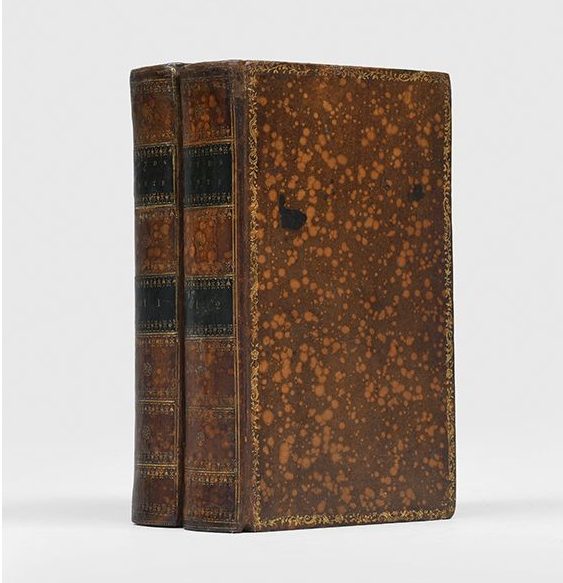

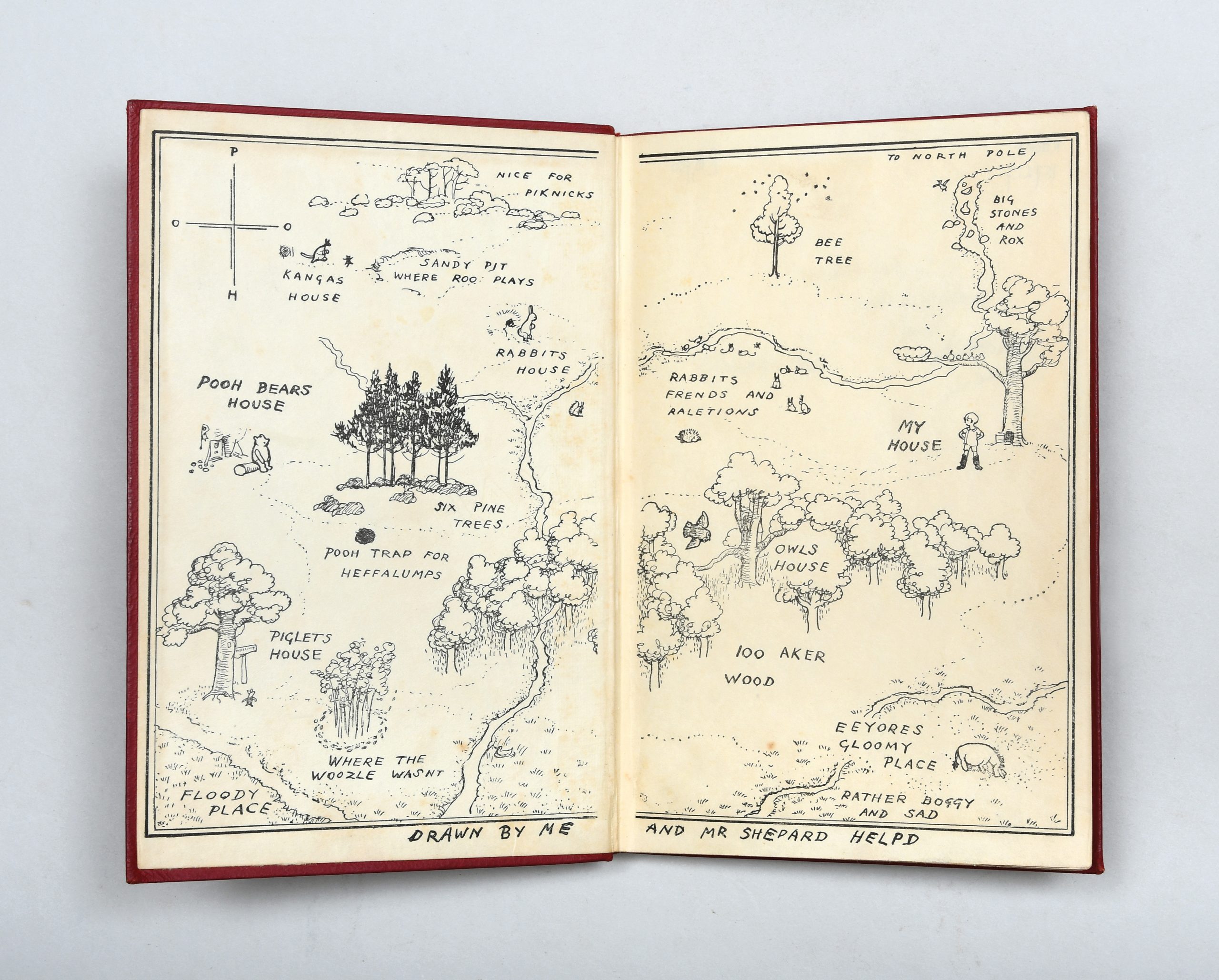

I feel like I have always been a collector of something – when I was a kid it was dolls, or crystal figurines, or Pokémon cards. I first got into collecting rare books just after college – to be completely honest I wanted to get a gift for myself to celebrate my graduation! I searched for a first edition copy of The Age of Innocence, one of my favorite novels, and I found one I could afford on AbeBooks, which was my first real introduction to the world of rare books. The feeling of holding the first edition of a book that was so special to me was like nothing else I had experienced – so much history and culture all represented in this one little volume. It was intoxicating! I’ve been hooked ever since. That’s how I became a book collector.

I have always loved fairy tales, so when I dedicated myself to building a more formal collection, they felt like a natural choice. There are so many different versions of these tales that have been told and published for centuries, and they remain incredibly important culturally because they’re often some of the first stories we tell children. I like to say you can see their influence everywhere, so there are many ways for the collection to keep growing.

I do have a wish list, but I don’t hold fast to it and mostly tend to pick things up as I discover them. I find I’m learning new things about fairy tales all the time, having new ideas about where I want the collection to go, so while there are certainly items I tend to keep an eye out for and hope to find one day, I focus more on the previously undiscovered treasures.

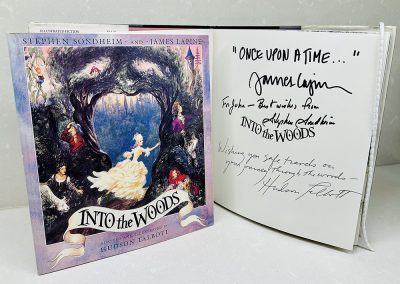

I absolutely maintain relationships with booksellers! Booksellers are the greatest allies in building a well-rounded collection. I think it’s a no-brainer to trust the experts, and I learn more about my own passions from the booksellers who so generously and thoughtfully spend their time looking out for me and my collection. Those bookseller/book collector relationships are invaluable.

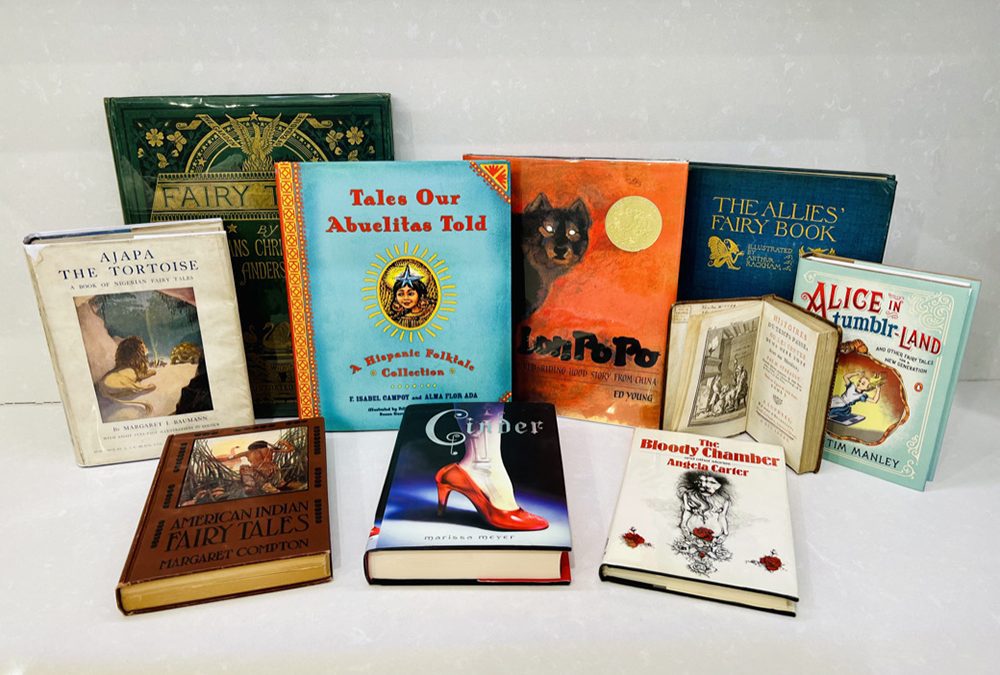

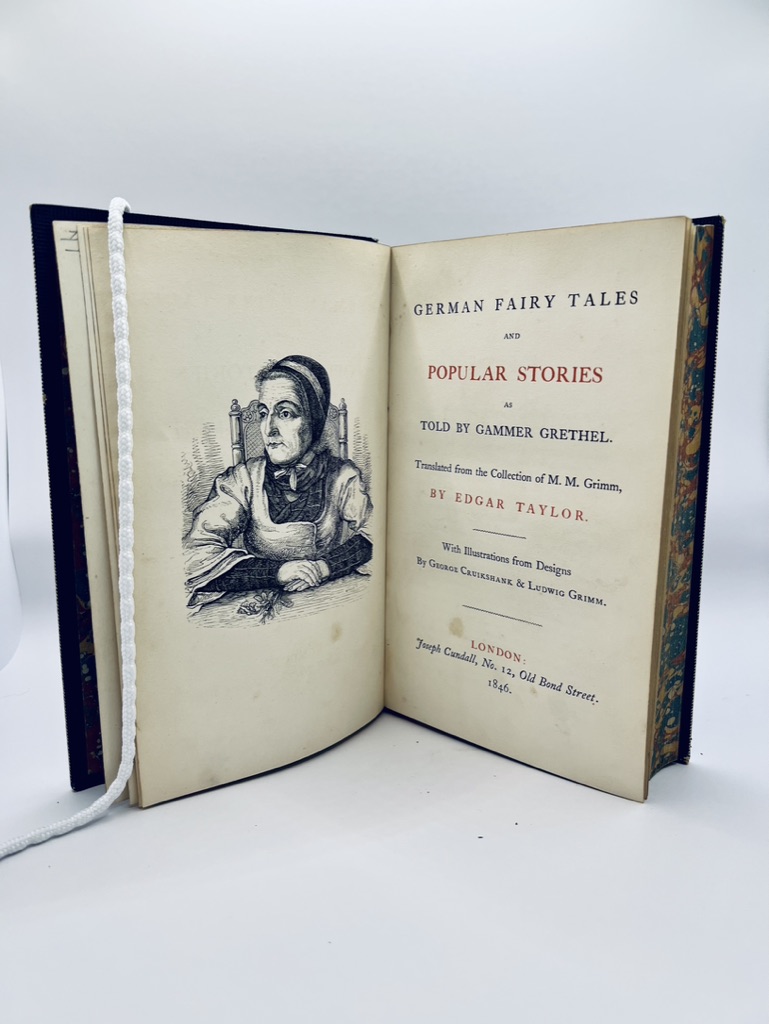

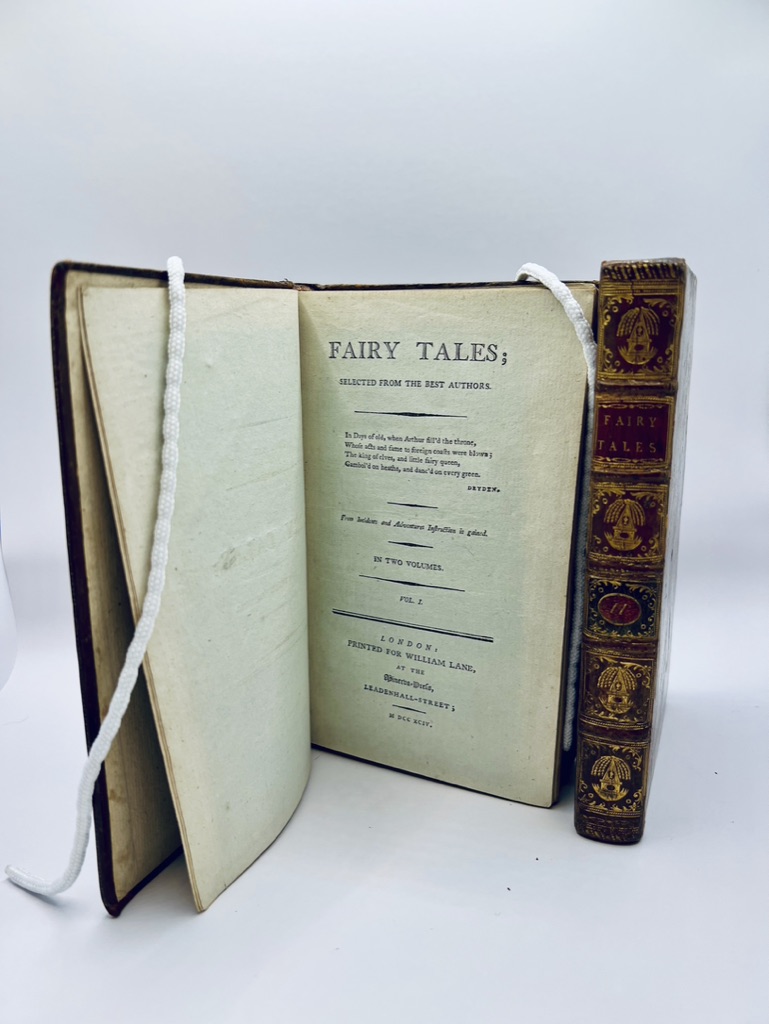

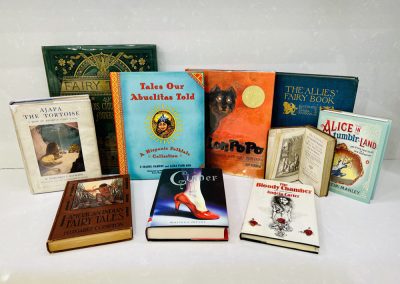

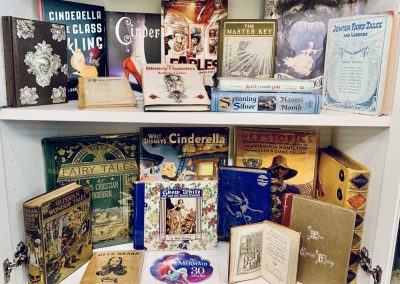

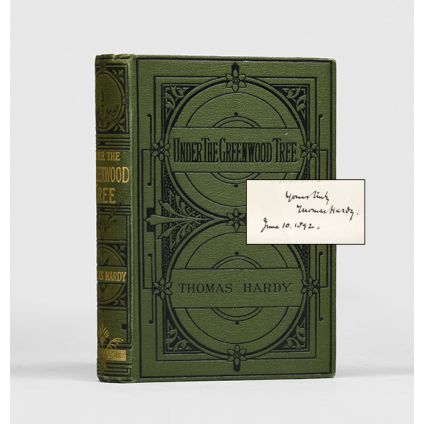

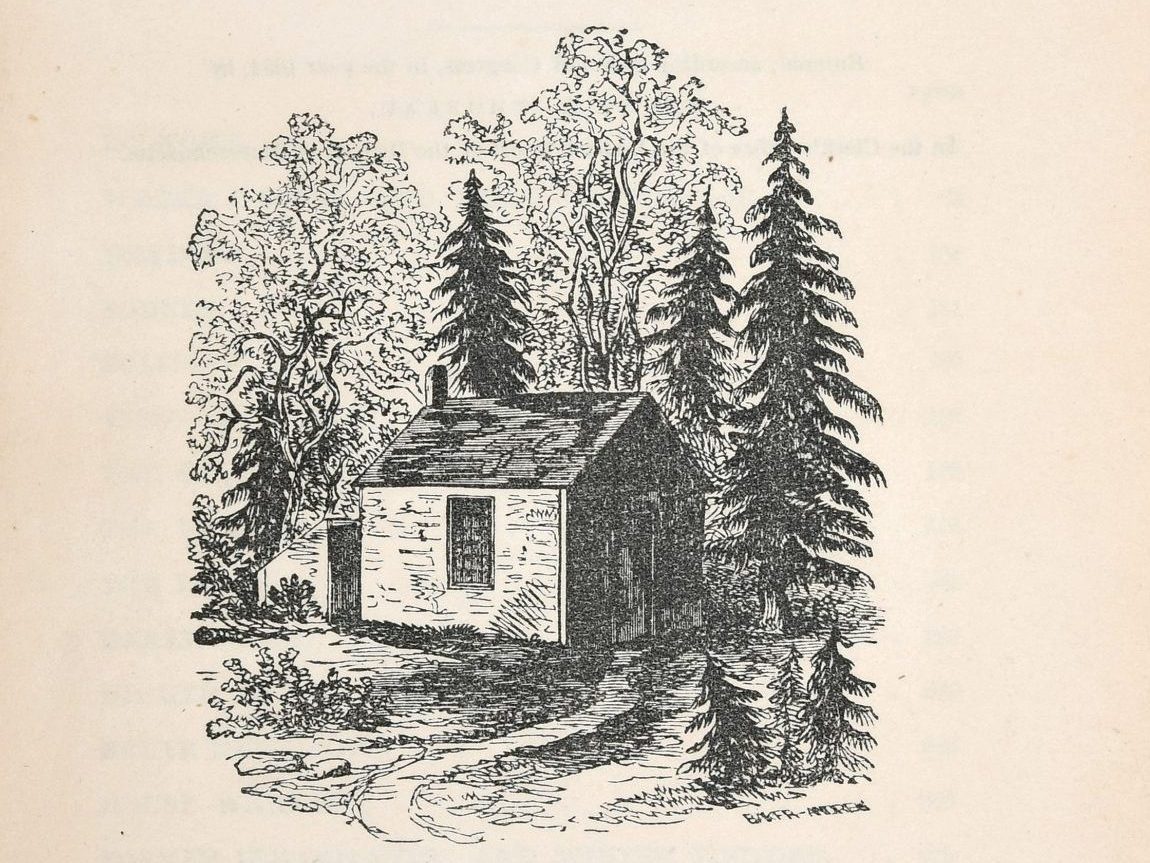

I think it depends on what kind of fairy tale collection you’re building. There are so many different ways you can go with a collection. If you want to get down to the basics in the canon of Western literature, I think it’s important to have collections of Charles Perrault, the Brothers Grimm, Hans Christian Andersen, and the French salonnières. These are the primary defining voices of the fairy tale as we know it today. Andrew and Leonora Lang’s “Coloured” Fairy Books are also hugely important for the genre, because they have fairy tales from all over the world. And if you want to go outside the Western canon, the Japanese crepe paper books from the late 19th and early 20th century are pretty magnificent.

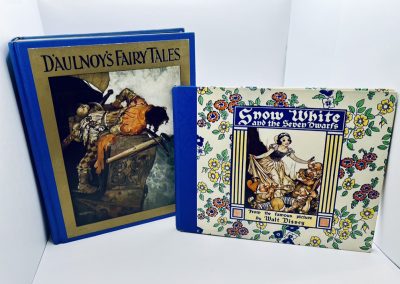

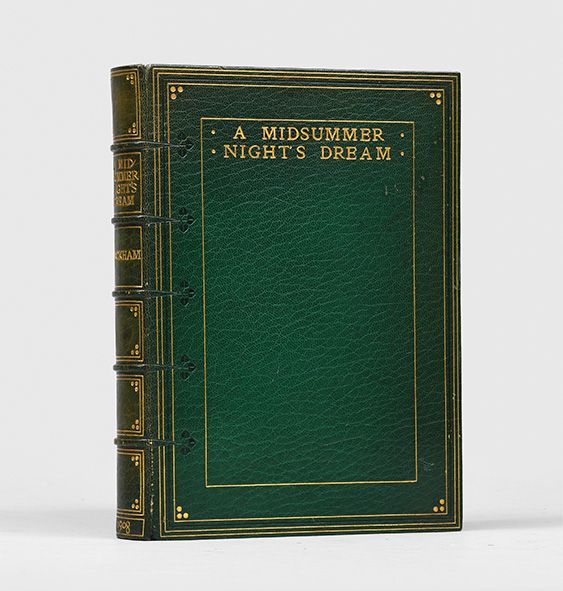

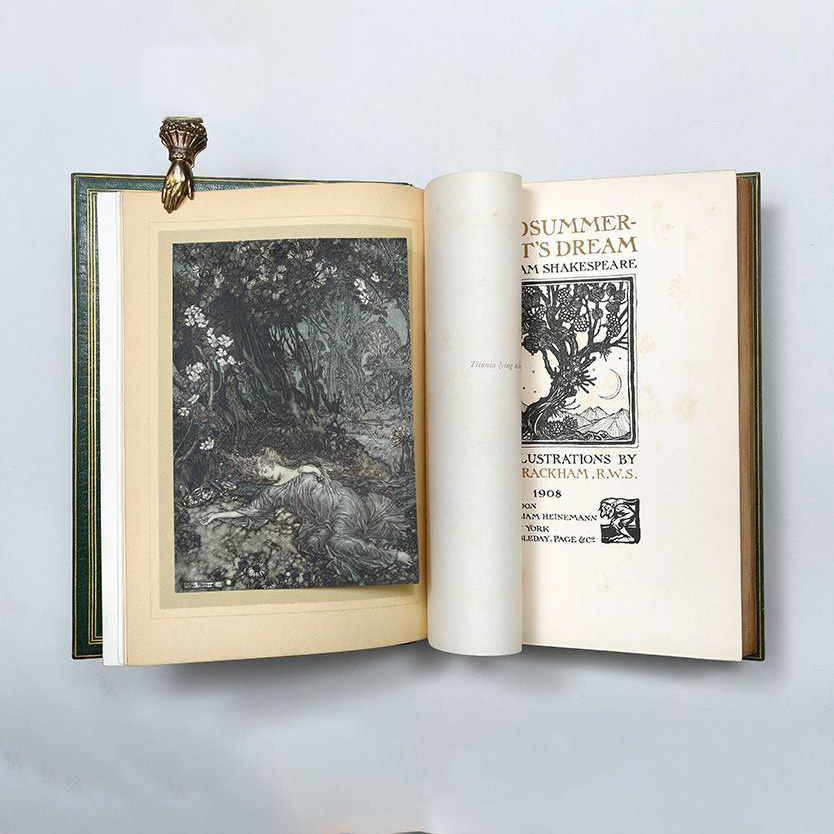

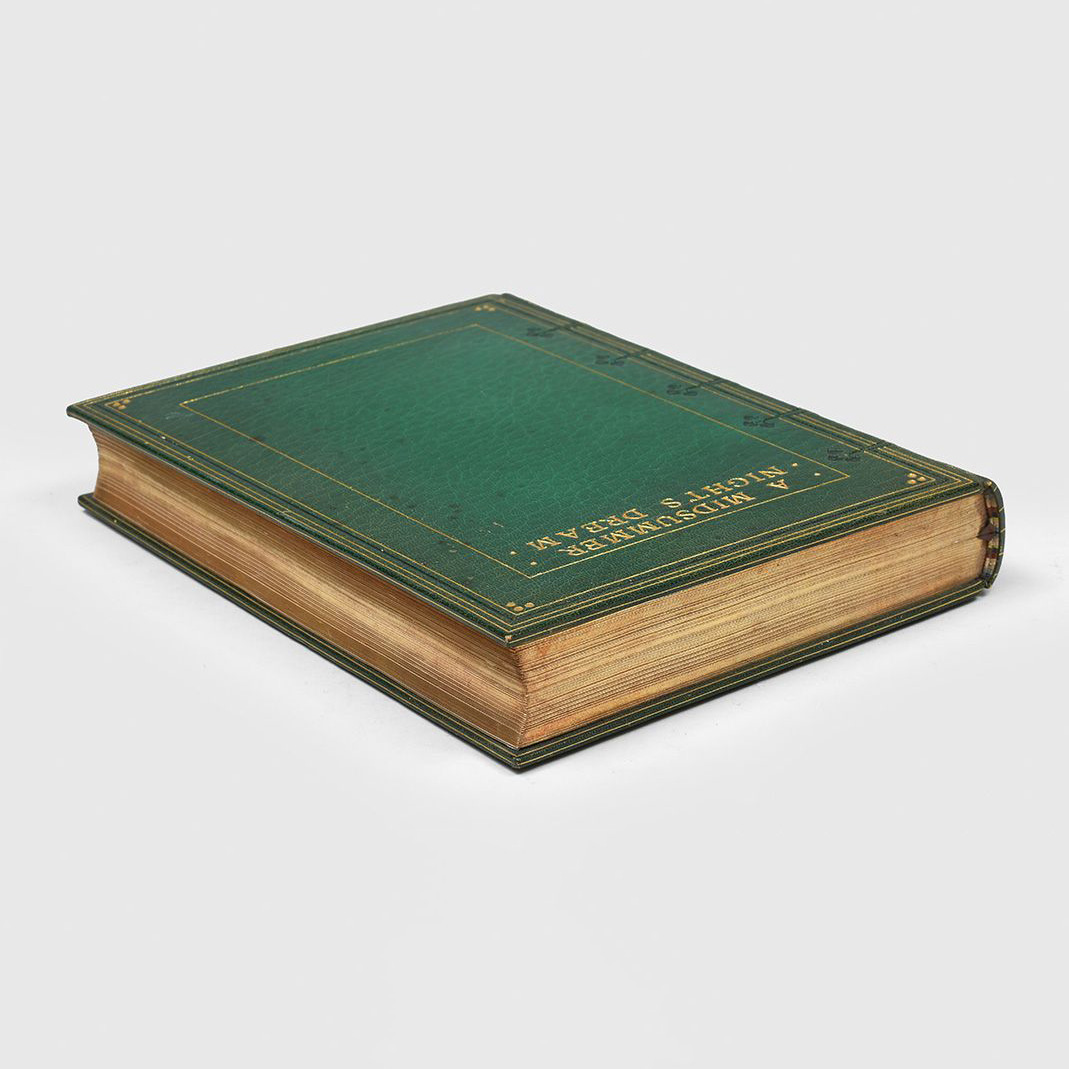

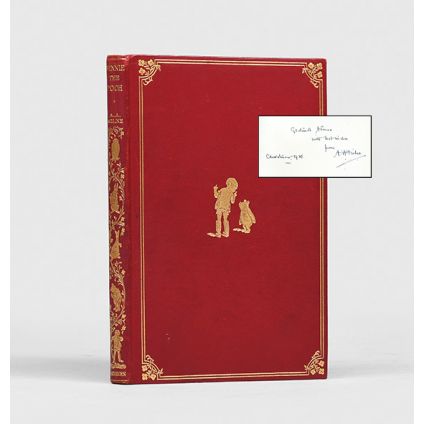

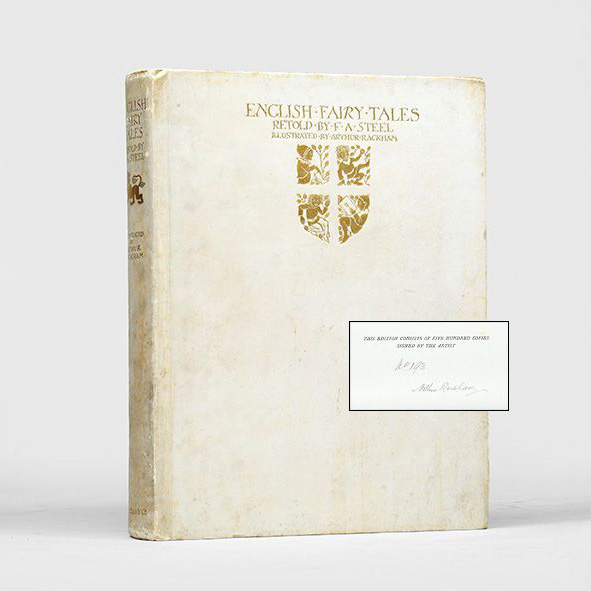

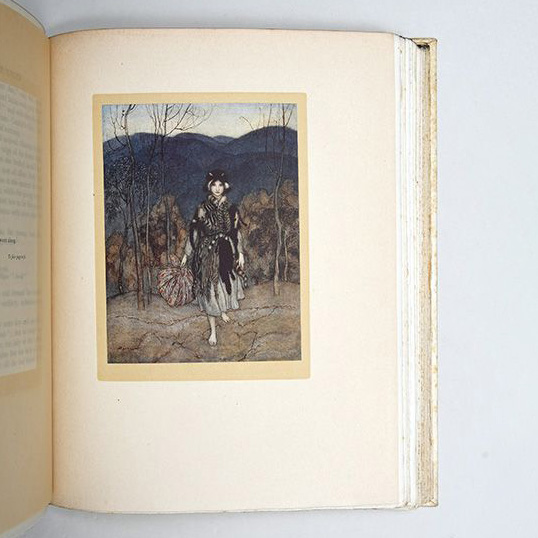

If you want to include books from the Golden Age of Illustration, works with art by Arthur Rackham would definitely be considered keystone items. Though it’s somewhat controversial, I think it’s also important to include Disney books, as the Walt Disney Company has had a massive influence on the evolution of the fairy tale and particularly how the public absorbs and reacts to these tales.

I include fairy tale scholarship in my collection, and some of the foremost voices I’d advise collecting are Jack Zipes, Marina Warner, and Maria Tatar. Finally, if you want to focus on more contemporary stories, authors like Angela Carter, Gregory Maguire, Helen Oyeyemi, Naomi Novik, and Neil Gaiman have done, and continue to do, incredible work adapting older tales and creating new ones.

My collection also includes more than books – I love to explore the influence of fairy tales in different mediums, so I have fairy tale artwork, items of fairy tale-inspired merchandise like makeup palettes inspired by The Little Mermaid and Sleeping Beauty, and clothing from fairy tale-based collections. Fashion is particularly interesting because of the relationship between fairy tales and clothing, so there is rich potential in this area for any collector – Alexander McQueen, Prada, and Dolce & Gabbana are just a few designers who have explored fairy tales in their clothing, with some like Karl Lagerfeld even contributing to new fairy tale publications. My favorite thing about collecting in these other areas is seeing how much of our culture comes from these stories – it all begins with the books.

But those are just a few examples from what is really a boundless genre. I’ve barely scratched the surface here.

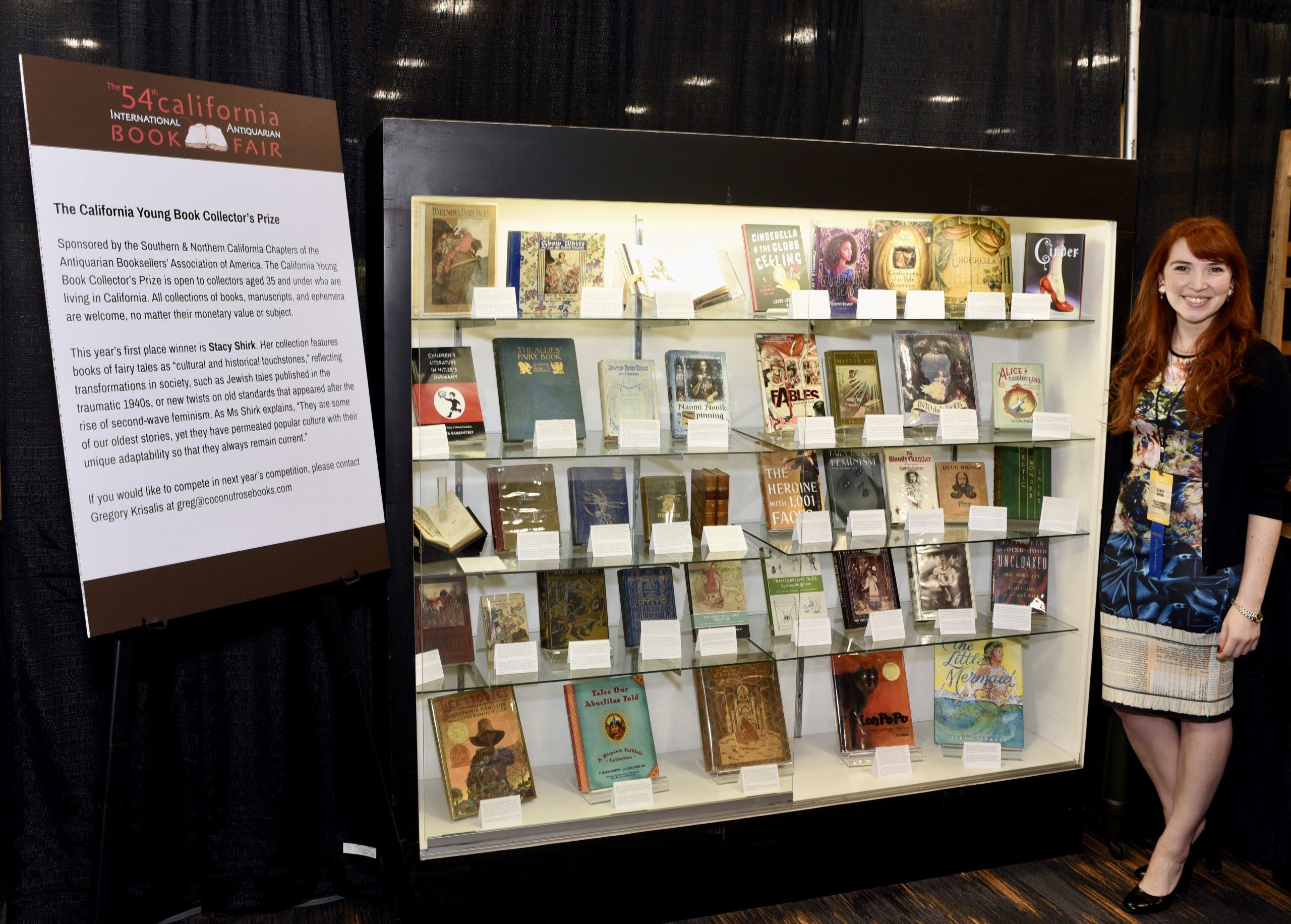

Stacy winning the California Young Book Collector’s Prize in 2022

The artists of the Golden Age of Illustration were incredibly important in shaping how we visualize these tales, even if many people don’t realize it today.

The Industrial Revolution led to an expansion of the middle class, as well as new technology to create art reproductions that were far more vibrant and detailed than had previously been possible – suddenly, publishers could bring fine art to the masses. For this reason, gorgeously illustrated deluxe books, also called “gift books,” became popular – particularly gift books for children of the middle and upper classes, who did not have to work. This is also when fairy tales started to become what we might call “sanitized,” because they were, more than ever before, made for children. Looking back to World War I, we see how readers were interacting with these illustrations in something like Arthur Rackham’s Allies’ Fairy Book (1916), in which Rackham altered his usual style (which often leaned towards the macabre) because he did not want to allude to the graphic images coming back from the war front – it was thought that could potentially disturb readers. Obviously, before film and television, these illustrations were the primary way that people had to visualize the fairy tales, and the stories that these artists chose to illustrate are often the ones that remain most well-known today, because the fantastical (and beautiful) images captured the imagination so fully.

The artists’ influence extends onto the screen – Walt Disney was a fan of Arthur Rackham, and asked the Disney animators to imitate Rackham’s style. When the fluid lines and dramatic shading of Rackham’s work didn’t translate clearly in animation, artists like Gustaf Tenggren created their own style inspired by Rackham’s. Tenggren’s work on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was so definitive that it’s difficult to picture those characters any other way now, with even some non-Disney adaptations using the color schemes and outfits of the 1937 Disney film. Kay Nielsen is one of my favorite artists and he completed concept art for a proposed Disney adaptation of The Little Mermaid which, while not used when he created it in the 1940s, was later used in the production of the 1989 film. So essentially, the work of these artists has reached through the decades and created an indelible image in the minds of many people of what these tales are supposed to look like.

This probably should not have been surprising to me, but I was shocked to see how much colonial influence can be found in fairy tale collections published during the Victorian era. I like to collect fairy tales from all over the world, and one thing I’ve had to grapple with is how much tales from colonized countries were revised when they were published in English. We often see evidence of this in the introductions, where the translators will say things like “we have picked the elements from the tales we feel our readers will like best,” or that these are stories were told in communities before “white people them to dwell in peace.” Folk and fairy tales often have community values embedded in them in some way, so to have the stories edited by colonizers or missionaries removes that cultural connection. It’s a hallmark of the genre that the stories change over time, from telling to telling, but this kind of alteration is different because of inherent bias. It’s important to preserve this history, of course, but luckily there are also many translators and scholars today doing the work to find and publish more accurate translations.

We can thank Madame d’Aulnoy for coining the term “fairy tale,” or “conte de fée,” which she first used in the late 17th century. But yes, there is absolutely a gendered aspect to the history of fairy tales. It’s no accident that one early title for Charles Perrault’s first fairy tale collection was “The Stories of Mother Goose” – fairy tales were heavily associated with women, specifically female storytellers in the home.

Many fairy tales began as folk tales that were told chiefly amongst women. There’s a reason many of these stories center women, both as protagonist and antagonist, and deal with what were, for so long, some of the chief concerns of women: marriage, confinement, childbirth, and sexual violence. The French salonnières, the women of the French salons who popularized the literary fairy tale, used these fantastical stories to comment covertly on topics that were not only highly relevant to their daily lives, but that could otherwise get them imprisoned or executed by the monarch and his authorities.

Madame d’Aulnoy’s life was not so different from many of the fairy tales that came out of the French salons. As a teenager, her father forced her to marry a man three times her age. Her first two children died very young. She was accused of treason (potentially on multiple occasions) and forced into hiding. Her mother and other female friends were also accused of various crimes, and one friend was even beheaded for retaliating against an abusive husband. For these women, court machinations and monstrous parents and husbands were a reality. Dying in childbirth, becoming orphaned, suddenly dealing with hostile stepfamilies, and competing with other women for limited resources was also part of their world. They infused their stories with magic and fantasy to disguise the fact that they were discussing very real problems.

So, there’s a long history of women telling these stories for other women. There’s also a long history of men adapting these stories, and publishing them under their own names. Charles Perrault attended the salons created by his female peers, heard their stories, and wrote his own adaptations. His plots were generally less complex and featured much more passive heroines, and as the French salons closed, his stories continued to be celebrated by the public whereas the French salonnières were criticized and faded to relative obscurity (though luckily there has been a renewed appreciation for their works in recent years). The earliest literary fairy tale writers, the Italians Straparola and Basile, acknowledged that their source material came from women storytellers, as did the Brothers Grimm a few centuries later. Andrew Lang published the “Coloured” Fairy Books under just his name, though in the introductions he credited the many women who helped gather and translate the stories, most especially his wife Leonora Lang. Even Hans Christian Andersen, who wrote many original tales as well as adaptations, wrote of how he got the inspiration for so many of his stories from the women in the hospital where his grandmother worked. Most famous male fairy tale writers got their stories from women, and many of them altered the heroines to fit a specific view of what a woman should be.

For anyone with further interest in this, I highly recommend reading Maria Tatar’s book The Heroine with 1001 Faces, published in 2021, and Marina Warner’s From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and Their Tellers (1995).

One of my favorite things about collecting fairy tales is exploring the newer publications in addition to older titles. The primary goal of my collection is tracking culture as represented in fairy tales told across time and place – we can learn so much about a society based on their fairy tales, especially because these stories are often the ones used to teach children morals. So, as a book collector, it’s been really fun to see how fairy tales have changed, and continue to change, reflecting shifting cultural values. That certainly includes revisionist retellings like those of Angela Carter and Anne Sexton. It also includes newer voices that in previous generations would likely not have been given the opportunity to publish.

I find that right now, there are two major trends. One is looking back, to stories like those of the French salonnières and also those older tales from Africa, Asia, and indigenous communities that were previously altered or ignored by English publishers, to bring those stories to light. Another is looking outward to feature new kinds of protagonists – we’re seeing a lot of fairy tales now featuring LGBTQ characters, such as Cinderella Is Dead by Kalynn Bayron, which imagines a land where Cinderella was a real person whose story is now used to oppress women. The main character in that book is a queer Black woman. Collecting absolutely helps champion the newer voices as well as those who had previously been underappreciated or unheard, because it makes those stories sit equal to and alongside those by Perrault and Grimm.

Being a book collector, my aim is to champion all of these voices to get a full picture of the humanity found in these tales that have been an integral part of nearly every culture on earth, for hundreds if not thousands of years. It’s an honor to be a small part of this storytelling tradition.

Recent Comments