Opening Gambit

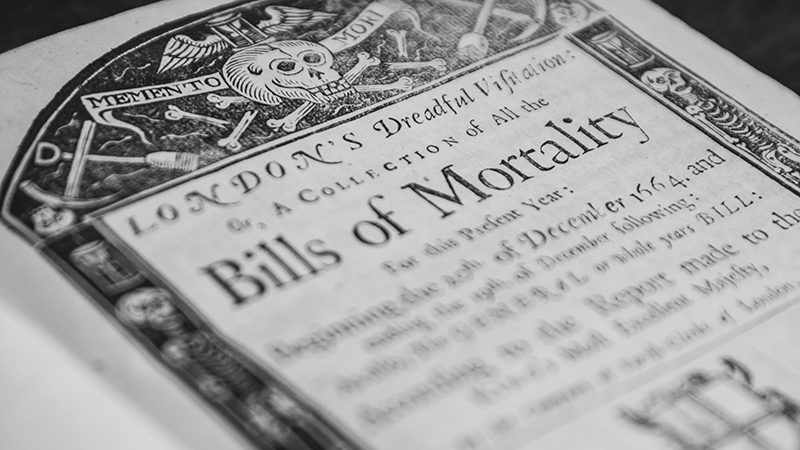

Paving the way for women in chess

The Chess Game, Sofonisba Anguissola (1555 – National Museum Poznań)

The Queen’s Gambit, the Netflix series about a troubled chess prodigy named Beth Harman, first aired in October, 2020. Within a month, it had been viewed by 62 million households worldwide. The Queen’s Gambit has become the platform’s most-watched series in 63 countries and, according to the streaming service, is also its most successful scripted limited series ever. Since then, chess websites and coaches have reported soaring interest in online matches, club membership, and private tuition. eBay alone saw a 276% increase in searches for chess sets following the show’s airing (The Guardian). Perhaps most remarkable is that an unusual proportion of those signing up are women; by December, 2020, chess.com had already seen a 15% uplift in female registerees (New York Times). To contextualise the significance of this, globally the ratio of male to female chess grandmasters (a prestigious title for the world’s best players) is, today, around 85 : 2. To put this another way, of roughly 1,700 chess grandmasters currently, fewer than 40 of them are women.

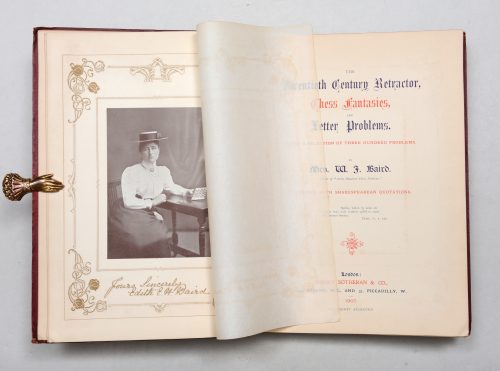

When Mrs. W. J. Baird’s The Twentieth Century Retractor, Chess Fantasies, and Letter Problems was published in 1907, prominent women chess players were even fewer and further between. Edith Baird was one of the most prolific composers of chess problems of her day and was sometimes referred to in the press as ‘The Queen of Chess’. A quote from one of her male contemporaries in Lasker’s Chess Magazine neatly demonstrates, however, that her reception in the male-dominated sport would not always have been so plauditory: the author asserts that women simply lack the ‘qualities of concentration, comprehensiveness, impartiality and, above all, a spark of originality’ required in order to become great chess players.

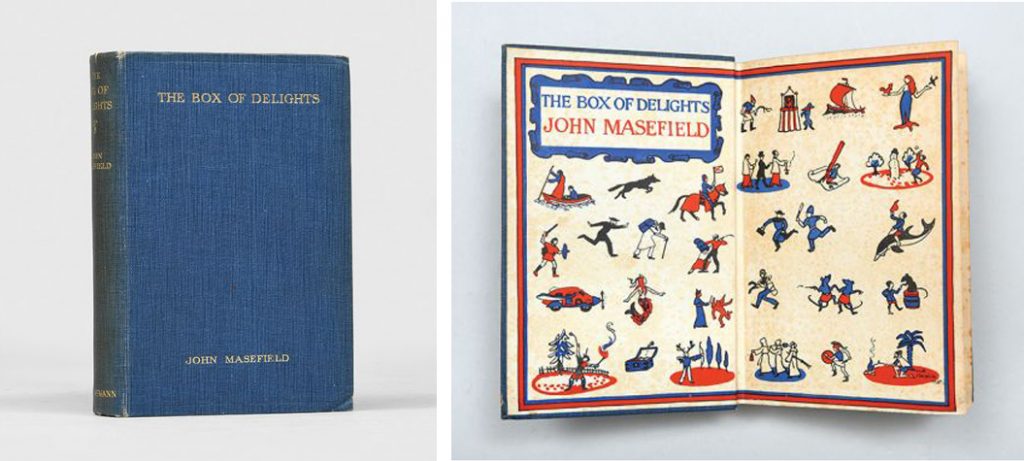

CHESS – BAIRD, Mrs W. J. The Twentieth Century Retractor, Chess Fantasies, and Letter Problems. 1907, £1,250.00.

The critique in Lasker’s Chess Magazine is echoed in comments made by male players decades later. Bobby Fischer, a chess legend and arguably the best player of all time, was deeply misogynistic as a precocious teen. In a 1962 interview, 19 years old and already a champion, he explained why women cannot play.

Interviewer: Do women make bad chess players?

Fischer: Oh, they’re terrible chess players… I don’t know why, I just guess they’re not so smart. […] They have never turned out a good woman chess player. Never one that could stand up to a man in the history of chess.

Fischer goes on to say that women shouldn’t ‘ with intellectual affairs’ but ‘should keep strictly to the home’ (though not cooking, he says, they aren’t good at that either). It should be noted that, when asked a similar question in the 1970s, Fischer did in fact express support for female inclusivity in chess. However, similarly sexist views continue to pervade the sport. In 2015, English grandmaster Nigel Short suggested that people “gracefully accept it as a fact” that men will always be inherently better players: “we just have different skills,” he argued (Time magazine). Short failed to mention the irony that he has been defeated by women (ibid.).

It is important to highlight that women have played chess for centuries. The Chess Game, a 1555 painting by Sofonisba Anguissola, depicts an intimate family scene in which Anguissola’s own sisters play together under the supervision of a governess. The patron saint of chess, is St Teresa of Avila, who wrote, as a senior nun in 1566, The Way of Perfection, a guide for her charges in which she playfully compared contemplative prayer to the discipline of mastering the game.

Now you will reprove me for talking about games, as we do not play them in this house and are forbidden to do so. That will show you what kind of a mother God has given you —— she even knows about vanities like this! However, they say that the game is sometimes legitimate. How legitimate it will be for us to play it in this way, and, if we play it frequently, how quickly we shall give checkmate to this Divine King! He will not be able to move out of our check nor will he desire to do so. (christianhistoryinstitute.org)

St Teresa later removed this analogy but modern editors reintroduced it. According to the Christian History Institute, The Way of Perfection aimed to ‘enthuse with a love of prayer and teach them how to practice it and therefore grow spiritually’. It continues to be influential in the Catholic approach to prayer.

There is, of course, ancient precedent for hostility towards women’s participation in chess. From its earliest days, chess was an intensely and inherently gendered game. Before the 15th century the movement of the queen was limited to just one diagonal square: ‘“aslant only”, as a medieval chess treatise put it, “because women are so greedy that they will take nothing except by rapine and injustice”’ (The Economist). It was around 1500 when the Queen was liberated and given free rein to traverse the chess board in one move. This apparently resulted in a new nickname for the game, ‘“madwoman’s chess” (The Independent). Nonetheless it is this later version that we know and play today.

Illustration of King Otto IV of Brandenburg playing chess with an unidentified woman, Manasse Codex, Große Heidelberger Liederhandschrift, Cod. Pal. germ. 848, f. 13r. Heidelberg University Library.

Although The Queen’s Gambit was praised for its technical precision (thanks to the guidance of former world chess champion Garry Kasparov), female experts identified a subtle yet crucial inaccuracy: the male characters were simply “too nice” to Beth Harman: this was the verdict of the world’s greatest woman chess champion, Judit Polgár, who has won more accolades than can be feasibly listed (though highlights include becoming International Grandmaster at just 15 years old, the youngest Grandmaster ever, as well as being the first woman to participate in a men’s world championship final). Sadly, Polgár was (and remains) an outlier. Today, only one of the world’s top 100 players is a woman, China’s Hou Yifan, and she is still just the third woman to have ever broken into this group. Polgár’s career continued to flourish until 2014, when she retired. She now runs a foundation and festival which promote and encourage chess among children and particularly girls.

After The Queen’s Gambit aired, The New York Times published an article in which it quoted sisters Rowan Field, 12, and Lila, 11, who both auditioned for the role of Beth Harman and have competed in prestigious international competitions. Their response to the series is poignant: simply that it “shows that there are female chess players who can be extremely good”.

In 1907, Edith Baird broke the norm with her chess , challenged expectations and became a leading voice in chess. Her Twentieth Century Retractor offers stimulating challenges to its owner; in Baird’s career she “composed more than 2,000 problems which… were noted for their soundness” (Hooper & Whyld 27), and there are remarkably few errors detected in her body of work. The book is also handsome – one of “the most elegant chess books ever to appear” (Hooper & Whyld 27), and uses Shakespearean quotes to enrich the solving experience and provide hints towards the solution.

But Baird’s work also represents what female chess players – and women in general – can achieve when defying stereotype threat and misogyny. Baird regularly contributed to newspapers, as well as the British Chess Magazine, and was a pioneer in multi-move retractor problems, chess puzzles in which the solver must work backwards, taking back a specified number of moves before a forward mating move can be performed; The Twentieth Century Retractor is, in fact, one of the first known collections of such problems. Now seems the perfect time to celebrate this important book.

Our regularly scheduled miscellany for the summer months, this catalogue showcases a selection of new acquisitions to our shelves.

For this catalogue, we are proud to partner with Beat – the UK’s leading eating disorder charity. Peter Harrington will donate 20 per cent of the list price of all catalogue orders to Beat to support its efforts to provide prompt help to those affected.

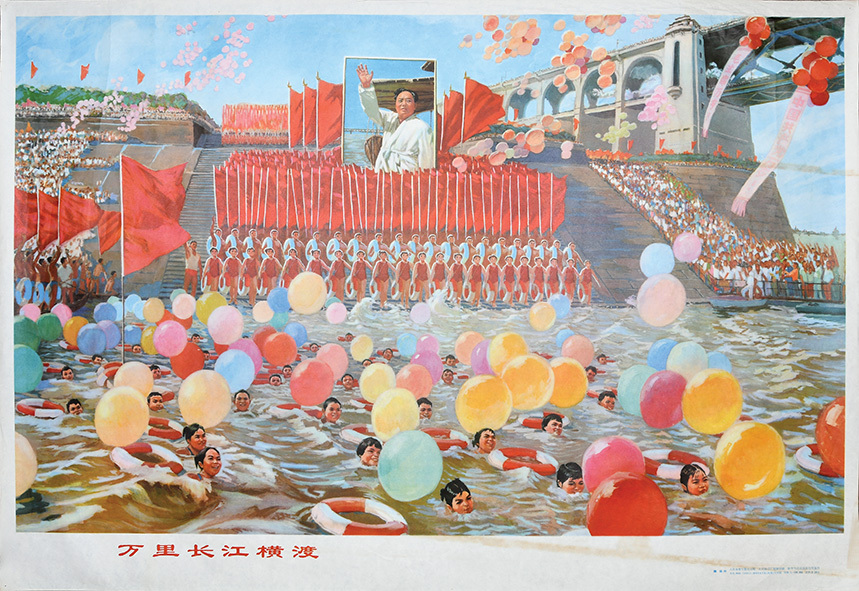

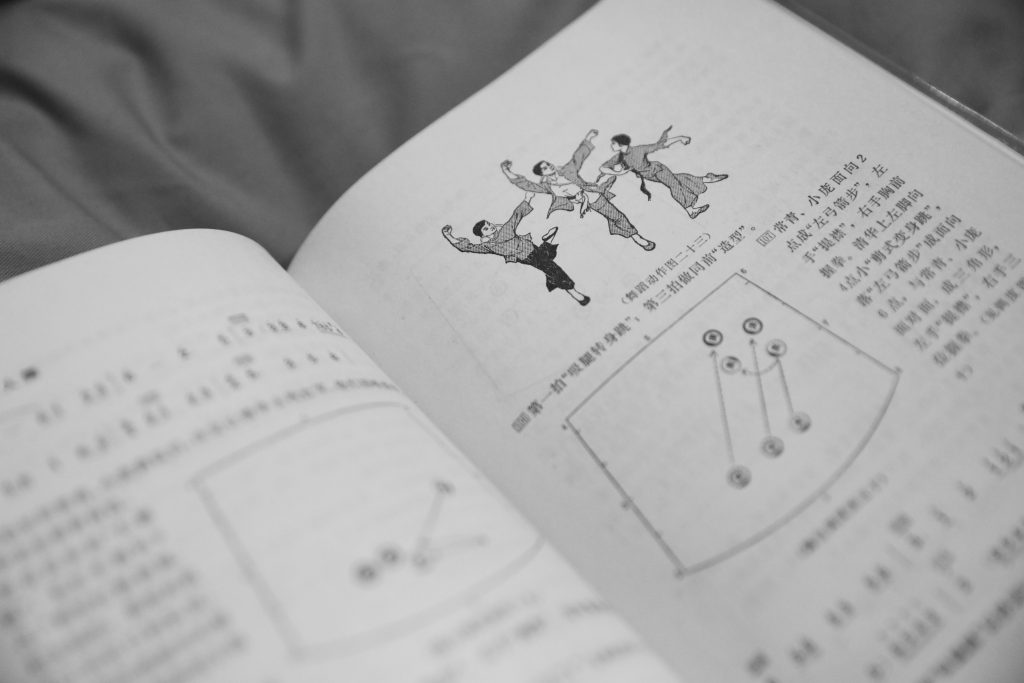

This selection exhibits the range of material available to the prospective collector of China-related materials. Earlier editions of Mao’s Little Red Book are probably the most well-known collectable Chinese book out there at the moment, and the historian in me relishes every chance I get to hold one.

This selection exhibits the range of material available to the prospective collector of China-related materials. Earlier editions of Mao’s Little Red Book are probably the most well-known collectable Chinese book out there at the moment, and the historian in me relishes every chance I get to hold one.

Recent Comments