On a sunny winter’s day in December, 1775, Jane Austen began life at home in the quiet country village of Steventon, Hampshire. The bustling parsonage where she was born was already occupied by her parents, four brothers and one sister, and another baby boy would join them two years later. “She is to be Jenny,” wrote her father, George Austen, in a letter to his sister-in-law (qtd. by Tomalin, 2012).

Mr. Austen was the rector of the local church (the Austens belonged to a large clerical family) and supervised the family farm, while also maintaining a dizzying cycle of debt and borrowing; Mrs. Austen busily managed the house, chickens and dairy, and was more of a pragmatic parent than a coddling one. The children’s sophisticated London-dwelling, French-speaking older cousin, Eliza Hancock, who owned jewellery sent from India by her military father and was heiress to a small fortune, would also feature heavily in the children’s lives, along with her widowed, financially independent mother, Philadelphia. Despite being 14 years apart, the cousins developed a close bond, and Eliza would eventually marry Austen’s favourite older brother, Henry.

Defying the high infant mortality rates of the time, all of the Austen children grew up healthy and into adulthood (although the parents’ second child, George, was sent to be raised elsewhere as he suffered from symptoms which may indicate cerebral palsy). The Austens were otherwise close-knit and, no matter their change in circumstances, would remain in each other’s lives. Sisters Jane and Cassandra were lifelong friends and confidantes, whose relationship may be reflected in the authentic female companionships of Austen’s novels. The author’s other siblings would work up the ranks of the navy, be adopted by or marry into upper-class families, or, like their father, join the clergy. Overall, the Austen children appear to have lived in a “cheerful home, whose atmosphere reminded one observer of ‘the liberal society, the simplicity, hospitality, & taste, which commonly prevail in different families among the delightful valley of Switzerland’” (ibid.).

Austen was not a diarist, and much of her correspondence has been destroyed or lost, in part due to a deep sense of privacy. Her sister Cassandra destroyed many letters for this reason, leaving us to speculate about what Austen might have felt during some of the most pivotal moments in her life: unfulfilled engagements, bereavements, family upheavals, illness and unexpected changes. This has widely engendered the assumption that her life was “uneventful” (so it was deemed by her brother and nephew in their own writing), but recent scholars have challenged this perception. Claire Tomalin’s excellent biography details the many intrigues, excitements and scandals the author experienced or was privy to in her lifetime, and which almost certainly informed her writing. Virginia Woolf, who proclaimed Austen “the most perfect artist among women” also considered her “a mistress of much deeper emotion than appears on the surface”.

Austen died from what was likely to have been cancer, aged 41, in 1817. Her life was the shortest of all her siblings. In this time she completed six novels, which have been beloved for centuries worldwide. Pride and Prejudice alone has sold tens of millions of copies globally and been adapted to screen for mass audiences and to great acclaim. This reserved genteel countrywoman, of whom we know relatively little, produced some of the greatest works of British literature. It is tantalising to imagine where she may be hidden in the stories themselves.

Below, we pay a visit to each of her much-loved novels.

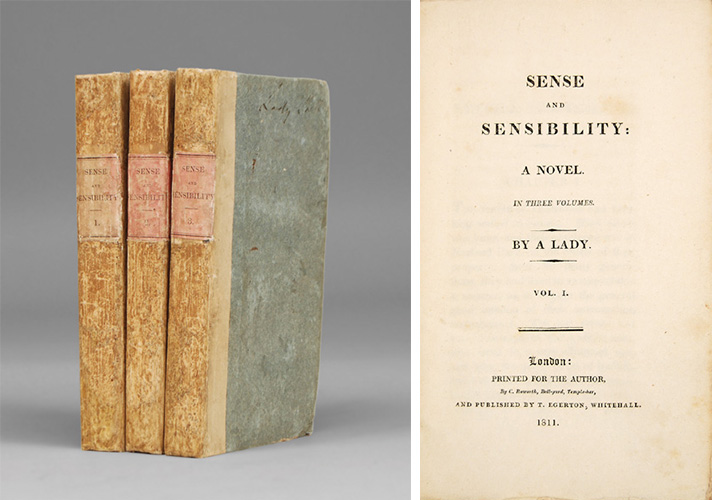

Sense and Sensibility, 1811

First edition of Sense and Sensibility in the original boards

Sixteen years after its first draft, in 1811, Austen spent a third of her annual household income to publish her first novel, Sense and Sensibility, through Thomas Egerton of the Military Library publishing house; she would receive a commission on sales. Where her name might have been printed on the title page was an anonymous, mysterious alternative simply reading, ‘By A Lady’.

Initially epistolary in form and titled Elinor and Marianne, in 1797 Austen decided to change the novel’s structure to direct narrative. It was renamed Sense and Sensibility, indicating that the contradictory natures of her main characters, two sisters – one stoical and sensible, the other impassioned and impulsive – would frame her narrative.

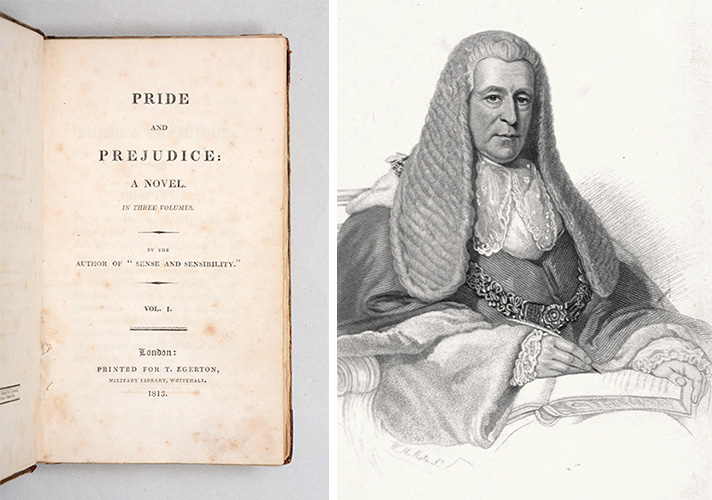

Pride and Prejudice, 1813

When Austen wrote the first draft of Pride and Prejudice, then titled First Impressions, in October, 1796, she was twenty – the same age as her heroine Elizabeth Bennet. She completed the first draft in nine months. By the time it was published, seventeen years later in 1813, she was thirty-seven. The novel’s title change once more signposted the central conflict in the book, this time between one of literature’s most famous couples, “Lizzy” Bennet and Fitzwilliam Darcy.

Left: Title page of the first edition of Pride and Prejudice. Right: Portrait of Thomas Langlois Lefroy by Willaim Henry Mote, 1855.

Pride and Prejudice’s instantly recognisable opening statement establishes the key theme of the novel – marriage: “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.” Although Austen’s opus widely explores and satirises the subject, in her own life her first and possibly only meaningful romance was cut short. From her letters we know Austen shared feelings with a family friend called Tom Lefroy, but their lack of combined wealth led to a family intervention which separated them: “The day is come on which I am to flirt my last with Tom Lefroy, and when you receive this it will be over. My tears flow as I write at the melancholy idea” (Jane Austen, qtd. by Tomalin). Biographer John Spence has gone so far as to suggest that the bold nature of “Lizzy” could have found inspiration in Lefroy, while Darcy’s restrained character may have reflected Austen herself. Austen would later refuse another proposal after changing her mind overnight, and her sister Cassandra’s fiancé died while on military expedition. Neither of them would ultimately marry.

Despite what has previously been perceived as her lack of personal experience, Austen’s most popular work, which established her as a success in her own time, is a triumph of satire; an astute social commentary on manners, education and, of course, the very nature of courtship and marriage.

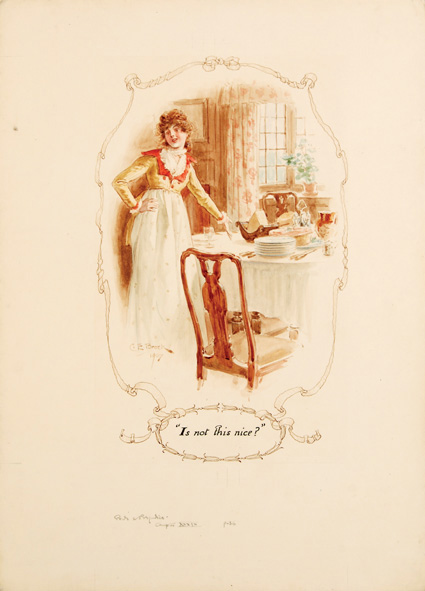

The original signed illustration for the 1907 edition of Pride and Prejudice, by Charles Brock

Mansfield Park, 1814

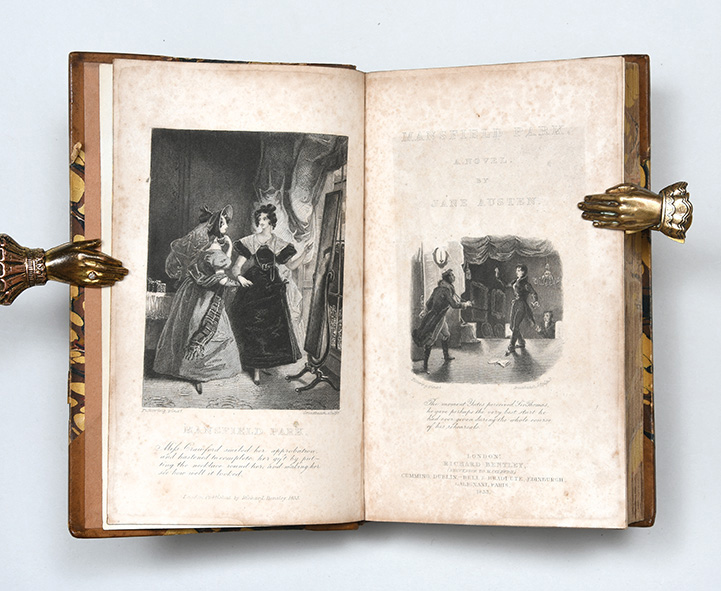

Title page and frontispiece for Mansfield Park, illustrated by Ferdinand Pickering, the first illustrator to interpret Austen’s works visually.

Another book of contrasts, Mansfield Park primarily concerns itself with questions of ‘right and wrong’. Austen’s characterisation of individuals and their society in her third-published book presents a binary moral code. Where Fanny Price is somewhat priggish, inflexible in her ethics and judgemental of others, Mary Crawford is witty and gregarious, resembling Austen’s other strong, wilful and unconventional female protagonists. However, Mary also belongs to morally corrupt London society; she is materialistic, capricious and, despite being shown as capable of caring for others, her actions are mostly self-centred. In the end, it is Fanny who prevails in Mansfield Park, much to the surprise and disappointment of some readers (including members of Austen’s own family), and to the approval and satisfaction of others.

Emma, 1815

Emma was published in 1815, the fourth and final book to be during Austen’s lifetime. After rejecting an offer from publisher John Murray II which would have included handing over the copyrights of Sense and Sensibility and Mansfield Park, she self-funded the printing of the Emma’s first 2,000 copies. In an unsigned review, Sir Walter Scott described how her style had changed the rules of novel-writing:

“ belong to a class of fictions which has arisen almost in our own times, and which draws the characters and incidents introduced more immediately from the current of ordinary life than was permitted by the former rules of the novel… The author’s knowledge of the world, and the peculiar tact with which she presents characters that the reader cannot fail to recognize, reminds us something of the merits of the Flemish school of painting. The subjects are not often elegant, and certainly never grand: but they are finished up to nature, and with a precision which delights the reader.”

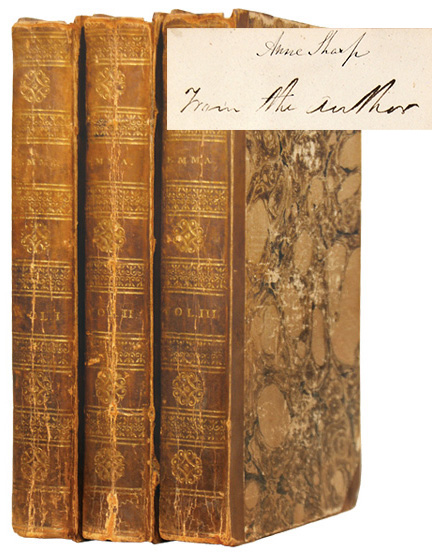

First edition of Emma, a rediscovered authorial presentation copy, to Austen’s great friend Anne sharp, the model for Mrs Weston in the novel: the only known authorial presentation copy of any Jane Austen novel to have appeared in commerce since publication.

It is amusing, perhaps, that the most iconic adaptation of Emma is a modern homage to it: a contemporised (at the time of its release) screen adaptation, set in an American high school in the ‘90s. Clueless introduced Austen’s story to the global mainstream and continues to be a cultural phenomenon, to the extent that some viewers won’t realise its basis in Austen’s novel. In fact, this screen adaptation is truer to the original than one might first appreciate: a privileged teenager interfering in her peers’ lives, constantly thinking of the future and not the present, planning and plotting, deluded about her own feelings, misunderstanding social cues and ultimately making things worse for everyone involved. The coming-of-age comedy has a universality about it and an enduring appeal for young women. Clueless, like Emma, is timeless.

Persuasion, 1817

Austen finished writing Persuasion when she was 40, in 1816. Around this time her health deteriorated; she did not dwell on what was, early on, a mild discomfort and would later take great pains to downplay her suffering. She finished the book in July but would eventually rewrite the two closing chapters – these drafts are the only manuscripts of Austen’s work to survive and are held by the British Museum.

“ a remarkably tight and economical habit of composition. The dialogue runs continuously, without paragraphing, closely packed in. The abbreviations show how she hurried and kept to essentials… Many nouns are capitalized in the old-fashioned way… some underlined as well, as though she paused to think of their significance and stress it: ‘Persuasion’, ‘Duty’.” (Tomalin, 2012.)

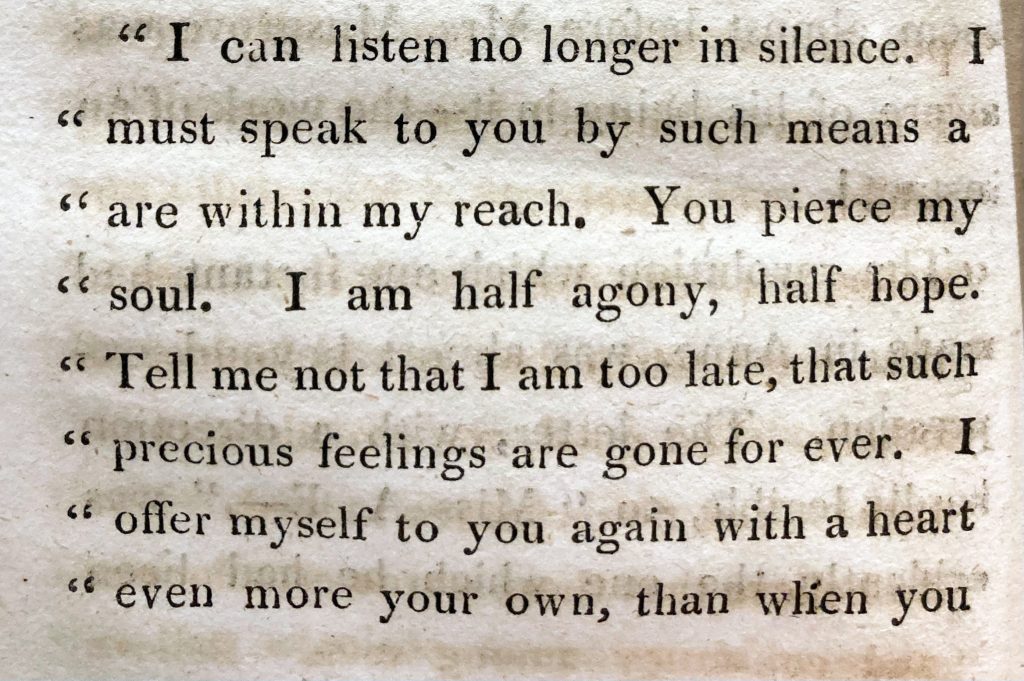

The famous letter written by Captain Wentworth to Anne Elliot, which forms the romantic climax of the novel

While the author may finally have been satisfied with her work, she did not begin the process of publication until a year later. It would eventually be published, along with Northanger Abbey, six months after her death.

Northanger Abbey, 1817

Northanger Abbey, initially structured as an epistolary novel (as Sense and Sensibility was), was also published posthumously, twenty years after Austen first penned it. A masterpiece of meta-literature, Northanger Abbey is a novel about novels and reading them. It is a playful comedy, a pastiche of gothic horror, and it subverts clichés. Unlike Elizabeth Bennet or Emma Woodhouse, Austen’s naïve protagonist Catherine Morland is plain and ordinary, lacking in suitors and not particularly bright. On the other hand, satirising popular gothic romances of the time, other clichés are farcically exaggerated: formidable architecture, sinister shadows, dark, creaking rooms, and the like. Meanwhile, the narrator punctuates the tale with bemused and witty observations, at odds with an otherwise foreboding setting. These contrasts come together as a commentary on fiction itself.

Illustration of Catherine Morland, artist unknown, 1833 Bentley Edition of Jane Austen’s Novels

Some of the commentary is explicit, though still couched in a humorously flippant tone: a novel is “only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour are conveyed to the world in the best chosen language”: a pithy statement that is true of any one of Jane Austen’s novels.