A bank collapses, and the public rush to withdraw their savings as the fear of losing everything sets in. It’s a familiar story, but isn’t necessarily one that exists only in the twentieth and twenty-first century.

In 1866, the London wholesale discount bank Overend, Gurney and Company collapsed, with debts of £11 million (£1bn in today’s money). It was the greatest casualty of the credit crisis in the later half of the 19th Century. The public panicked, and flocked to Lombard Street in protest.

Two decades previously, the Banker Charter Act of 1844 had restricted the powers of British banks, giving exclusive note-lending powers to the Bank of England, thus giving them greater and greater power as Britain’s central bank, but without much reform to the institution.

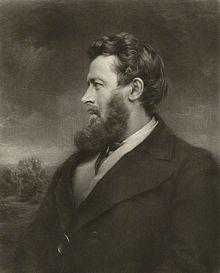

It was against this financially backdrop that Walter Bagehot, editor-in-chief of The Economist, published Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market, which has come to be known as the “most frequently quoted book in the entire banking literature”.

Addressing Victorian businessmen, Bagehot attempted to show how the system could be modernised from within, without reforming the institution as a whole. His ideas appealed perfectly to his demographic: the pre-existent central bank statesmanship should be approached with a laissez-faire philosophy.

The fractional reserve banking system had made Britain immensely wealthy, investing gold in projects such as railways and factories, which turned over greater profit year-by-year, and keeping only a small amount in gold stores. However, according to Bagehot, this wealth did not translate to stability.

In the wake of the credit crunch of the previous decade, Lombard Street proposed the following idea: adjust gold reserves depending on the condition of the economy. If the Bank of England did so, it should be able to protect itself against the large amounts of financial damage it might incur if the market underwent a dramatic fluctuation. Should the worst happen, ‘Bagehot’s Dictum’ posed a solution: insolvent banks should not be helped by the Bank of England, large amounts should be lent freely to solvent banks, and penalties should be accorded to illiquid and solvent banks in need of rescue.

The shifting class system of late Victorian Britain also provided inspiration for Bagehot. The new emerging entrepreneurial classes had to be incorporated into the study of economics, which Bagehot saw as being as much about cultural and social shifts as straight-forward matters of money. It is ideas such as this that have had longevity with bankers, and is part of the reason why Lombard Street has remained a must-read.

But Bagehot went a step further. He suggested that banks should do more than simply being aware of changes to the economy and society: they should adjust themselves accordingly. These changes would strengthen the pre-existing system without requiring any extensive overhaul or reform.

Bagehot was an influencer on the periphery of the public eye, having written two books on political philosophy and dozens of historical and literary essays. Despite the fact that he never entered parliament, and therefore could not enact the changes he thought needed to be made, Gladstone referred to him as ‘a kind of spare Chancellor of the Exchequer’.

John Maynard Keynes, greatly influenced by Lombard Street, wrote of it as “an undying classic”, and even after the financial crisis of 2007, ‘Bagehot’s dictum’ was cited by a number of central bankers. It is a testament to Bagehot’s success that he recommends a system which will be familiar to today’s bankers.

Hundreds of economics and social sciences titles are available at Peter Harrington. The collection can be viewed online in its entirety here.