The story of the genesis of Frankenstein is well known. The stormy night in June 1816 at the Villa Diodati on the shores of Lake Geneva, during which a ghost-story writing contest between Byron, the Shelleys, and Byron’s physician Polidori led to the composition of Mary Shelley’s novel, has entered literary history. According to Mary’s recollection in the preface to the third edition of Frankenstein, the contest itself was Byron’s idea:

In the summer of 1816, we visited Switzerland, and became the neighbours of Lord Byron. At first we spent our pleasant hours on the lake, or wandering on its shores… But it proved a wet, ungenial summer, and incessant rain often confined us for days to the house. Some volumes of ghost stories, translated from the German into French, fell into our hands. … “We will each write a ghost story,” said Lord Byron; and his proposition was acceded to…

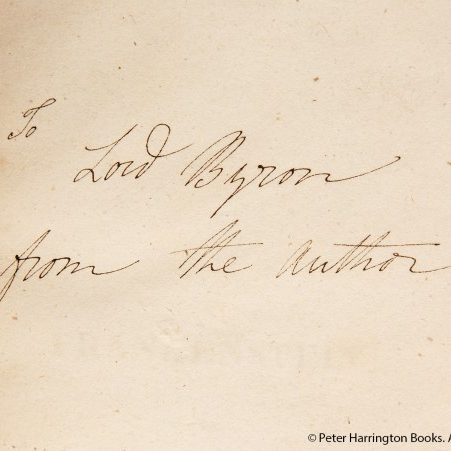

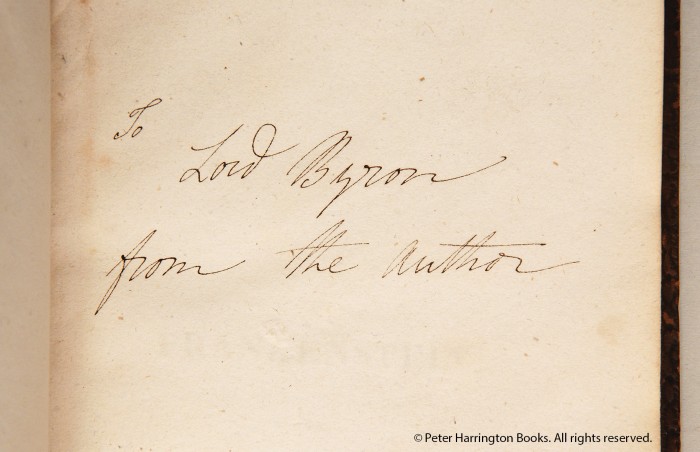

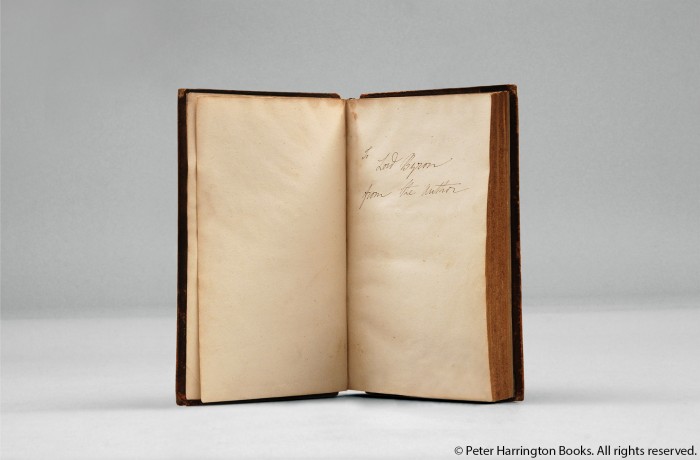

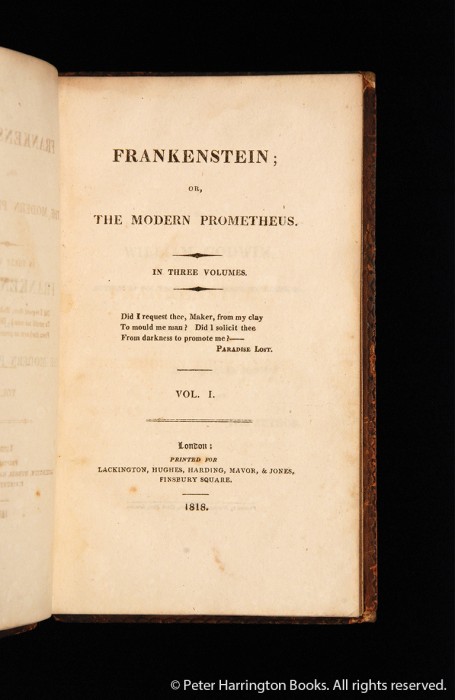

Title page to the first edition of Frankenstein by Mary Shelley (1818), Lord Byron’s copy with Shelley’s inscription.

Mary was “the daughter of two persons of distinguished literary celebrity”: the philosopher William Godwin and his equally radical wife, the feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, who had died of postnatal complications resulting from Mary’s birth. In some sense, Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin was a literary celebrity from the moment of her birth. By the time of her scandalous elopement and marriage to the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Shelley knew that great things were expected of her.

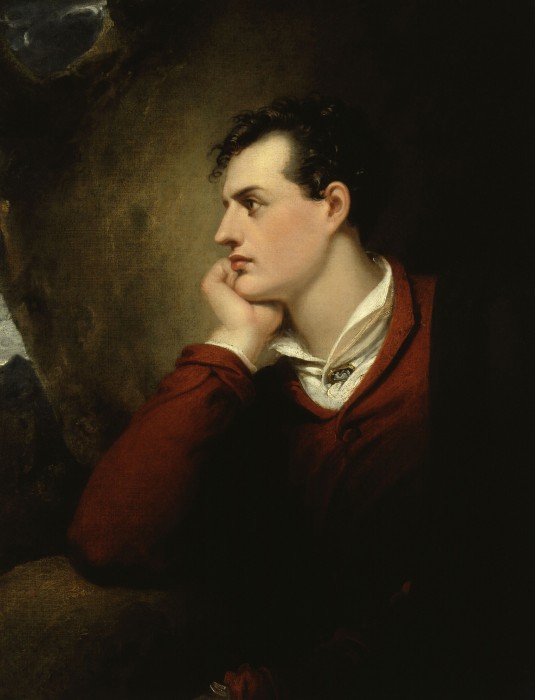

Her celebrity was, however, far outshone by that of Byron, who on publication of the first cantos of Childe Harold in March 1812 “woke to find himself famous”. He was a tourist attraction in London, with gawpers lining the pavements outside the house where he first met Mary in April 1816. Byron already knew and admired both her father, Godwin, and her husband’s poetry. He was planning to leave England in a few days, and it was decided that Mary and Percy should join him in Switzerland, where the Shelleys would take a villa just along the lake shore from his lodgings at the Villa Diodati.

The Shelleys left Geneva to return to England in September 1816. Completed by May 1817, Frankenstein was placed with the firm of Lackington & Co., who published it on 1 January 1818 in an edition of only 500 copies. Lackington’s handwritten account of expenses for printing and publishing Frankenstein indicate that six copies were given to the author.

On 11 March 1818 the Shelley entourage left England again, this time for Italy. Mary was expecting to meet Byron and hoped to present this copy of her book in person. But Byron proved elusive, and Mary made her presentation at one remove, sending the book by post. From Milan, Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote to Byron, who was in Venice, on 28 April 1818:

You will receive your packets of books. Hunt sends you one he has lately published; and I am commissioned by an old friend of yours to convey “Frankenstein” to you, and to request that if you conjecture the name of the author, that you will regard it as a secret. In fact, it is Mrs. S.’s. It has met with considerable success in England; but she bids me say, “That she would regard your approbation as a more flattering testimony of its merit.”

Byron’s approbation in the form of a reply, if there was such, has not survived. His only direct recorded reference to Frankenstein is in a letter to John Murray, from Venice, 15 May 1819, in which he corrects various misconceptions Murray has been told about the storytelling competition at the Villa Diodati:

The story of the agreement to write the Ghost-books is true—but the ladies are not Sisters—one is Godwin’s daughter by Mary Wolstonecraft—and the other the present Mrs. Godwin’s daughter by a former husband … Mary Godwin (now Mrs. Shelley) wrote “Frankenstein”—which you have reviewed thinking it Shelley’s—methinks it is a wonderful work for a Girl of nineteen—not nineteen indeed—at that time.

Byron’s copy of Frankenstein was presented in the year of its publication to the most important literary figure of Mary’s acquaintance, her and her husband’s close friend, the poet of the age, and the person credited by her with first inciting its composition. It is impossible to imagine a finer association.

Provenance: After Byron’s death, in January 1825 the remains of his library—consisting of five boxes of books—were shipped back to England. The books were dispersed among Byron’s friends, including his executor John Cam Hobhouse, and at a three-day sale of his library, beginning 6 July 1827, at R. H. Evans’s rooms in Pall Mall. This copy was not among the items offered for public sale. It was discovered in 2011, without its accompanying second and third volumes, in the library of Douglas Patrick Thomas Jay, Baron Jay (1907– 1996). Educated at Winchester and New College, Oxford, Douglas Jay was an influential Labour party politician. The inscription was authenticated by the Bodleian Library and the book sent by them for exhibition (alongside the original manuscript of Frankenstein) at the New York Public Library in the exhibition “Shelley’s Ghost”, 24 February to 24 June 2012.