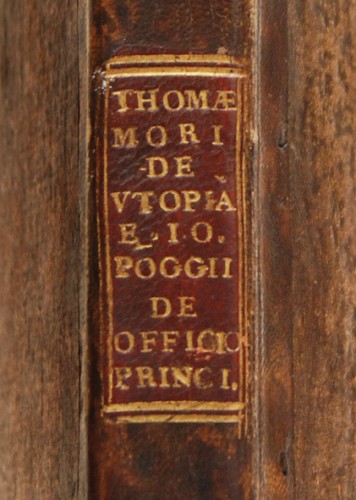

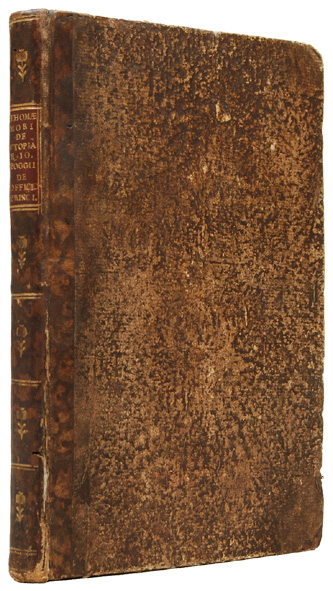

Some days in a rare book shop are definitely more exciting than others. For instance, last week I had the privilege of cataloguing the first edition of Thomas More’s Utopia, recently purchased at auction by Peter Harrington for a customer. This copy is bound in late-18th-century sheepskin with a red morocco label to the spine, as you can see below. In the photo above the book is open to the map of Utopia and a table of the island’s alphabet.

A truly rare book, OCLC lists only 18 institutional copies. While no comprehensive census of private copies has been undertaken, only seven have appeared at auction during the last thirty-five years, so it is reasonable to estimate that 10-15 copies are in private libraries.

Morocco Spine Label

Thomas More by Hans Holbein 1527

Born in London in 1478, Thomas More embodied many of the dichotomies of the late Middle Ages. His family built its wealth through trade before joining the ruling elite (his grandfathers were a baker and a chandler, while his father was a barrister and judge), and even while walking the corridors of power More would express pride in his family’s humble origins. Showing intelligence at an early age he was schooled for a secular legal career, but was also interested in religion and the humanist movement. It was his intellectual engagement with these contradictory spheres that would make More a towering figure in Renaissance thought.

As a young man More struggled to reconcile secular governance with the demands of Christianity. By his early thirties he was writing histories and epigrams that celebrated royal power but also betrayed “a profound sense of unease with the corruption often associated with kingship” (ODNB). These concerns were given their full expression in Utopia, an imaginative satire written just as he was embarking on a career in the English royal court.

The publication of Utopia is an excellent demonstration of the tightly-knit network of intellectuals and publishers that crossed Europe during the Renaissance. The book was inspired by a 1515 trip to Antwerp, where More visited Erasmus’s friend, the scholar Peter Gilles. Once More had returned to England the three men maintained a correspondence on the text, collaboratively editing and titling it, while Gilles created the Utopian alphabet. In November 1516 the manuscript was entrusted to another friend of Erasmus, the prominent printer Thierry Martin, whose device appears in the colophon (below). In mid-December More wrote to Erasmus, calling the book “ours” and saying that he waited on its completion just as a mother would the return of her son from abroad. The first copies appeared in early January 1517.

Printer’s Device of Thierry Martens

Utopia became an immediate success and quickly went through several editions, but it was a challenging and widely misunderstood book. Using irony and complex wordplay it criticized the flaws and injustices of contemporary states while offering solutions for modern leaders. The fictional island of Utopia, from the Greek for “nowhere”, demonstrated some of the traits of an ideal state such as wisdom and tolerance (though it was never meant to depict a perfect nation). Additionally, the book was a reaction to the rapid change engendered by the Renaissance, with More arguing that the carefully considered reform of existing social and legal systems was far preferable to their wholesale overthrow.

Most significantly, Utopia is More’s reconciliation of Christian morality and humanist idealism with the messy business of governance. Because rulers could not be trusted to act justly of their own accord, it was necessary for principled advisers to subtly guide them. As the character Morus puts it:

… there is another philosophy, more practical for statesmen, which knows its stage, adapts itself to the play at hand, and performs its role neatly and appropriately … If you cannot pluck up wrongheaded opinions by the root, if you cannot cure according to your heart’s desire vices of long standing, yet you must not on that account desert the commonwealth. You must not abandon the ship in a storm because you cannot control the winds.

For 20 years More successfully balanced these conflicting prerogatives. He rose to the post of Lord Chancellor, only to fall from favor and face execution in 1535 after taking a moral stand against Henry VIII’s divorce and usurpation of Papal authority. More’s public life and death demonstrated his commitment to the ideals he had espoused in Utopia, and it remains his most influential and popular work, inspiring later thinkers such as Samuel Johnson, Voltaire, and Jonathan Swift. In its grappling with issues of morality, justice, and power it is as relevant today as when it was first published.

Thomas More’s Utopia