By Madeleine Joelson and Kate Clairmont

“In matters of grave importance, style, not sincerity, is the vital thing.”

So says The Importance of Being Earnest’s Gwendolen upon discovery of her lover’s false identity and its accompanying deception. The sentiment is typical of Wilde, who did not himself take his final play seriously: he referred to it as his response to an American producer’s request for a play “with no real serious interest.” The result, of course, is the author’s most famous and most-adapted play–one which has outlasted many more “serious” works of the period. Gwendolen’s flippant response to Jack’s lie gets to the heart of the play’s interest in life as a performance. In this, the play may be said to mirror its author, who famously blurred the lines between life and art: “I have put all my genius into my life; I have put only my talent into my works.” It is therefore Wilde’s persona that is at times best remembered–something he crafted, altered, curated, and put on display throughout his life.

The conceit of The Importance of Being Earnest hinges on a similar, if less aesthetic, performance of one’s own identity. Its central characters, Algernon Moncrieff and Jack Worthing, perform different personas when they are in the city or the country. The ensuing plot is so labyrinthine as to be ridiculous (and hilarious). Algernon and Jack embody their author’s wit–W.H. Auden described the play as “pure verbal opera”–and their decadent habits of “getting into scrapes” have left a lasting picture of British fin de siècle dandyism. The play culminates in a withering critique of Victorian England’s obsession with roots, status, and decorum: an obsession that forces Wilde’s characters into their double lives even as it eventually unmasks them.Famously, the play’s opening night–Valentine’s Day 1895–would witness events that eventually led to Wilde’s own public unmasking: a tragic set of legal proceedings that have since become known as the Wilde trials.

In the early 1890s, Wilde had a well-known affair with a young nobleman named Lord Alfred Douglas who was 17 years Wilde’s junior. Beginning in 1894, the affair began to rouse the suspicions and eventually the ire of Lord Alfred’s father, the Marquess of Queensberry. Queensberry harassed Wilde and his son for almost a year, threatening restaurant owners who allowed them on their premises and even showing up at Wilde’s home with a prize fighter and a threat of violence. On the opening night of The Importance of Being Earnest, Wilde caught wind of a plot on the part of Queensberry to sully the stage with a bouquet of rotten vegetables. In response, he surrounded the theater with policemen and therefore ensured that Queensberry would be barred from entry.

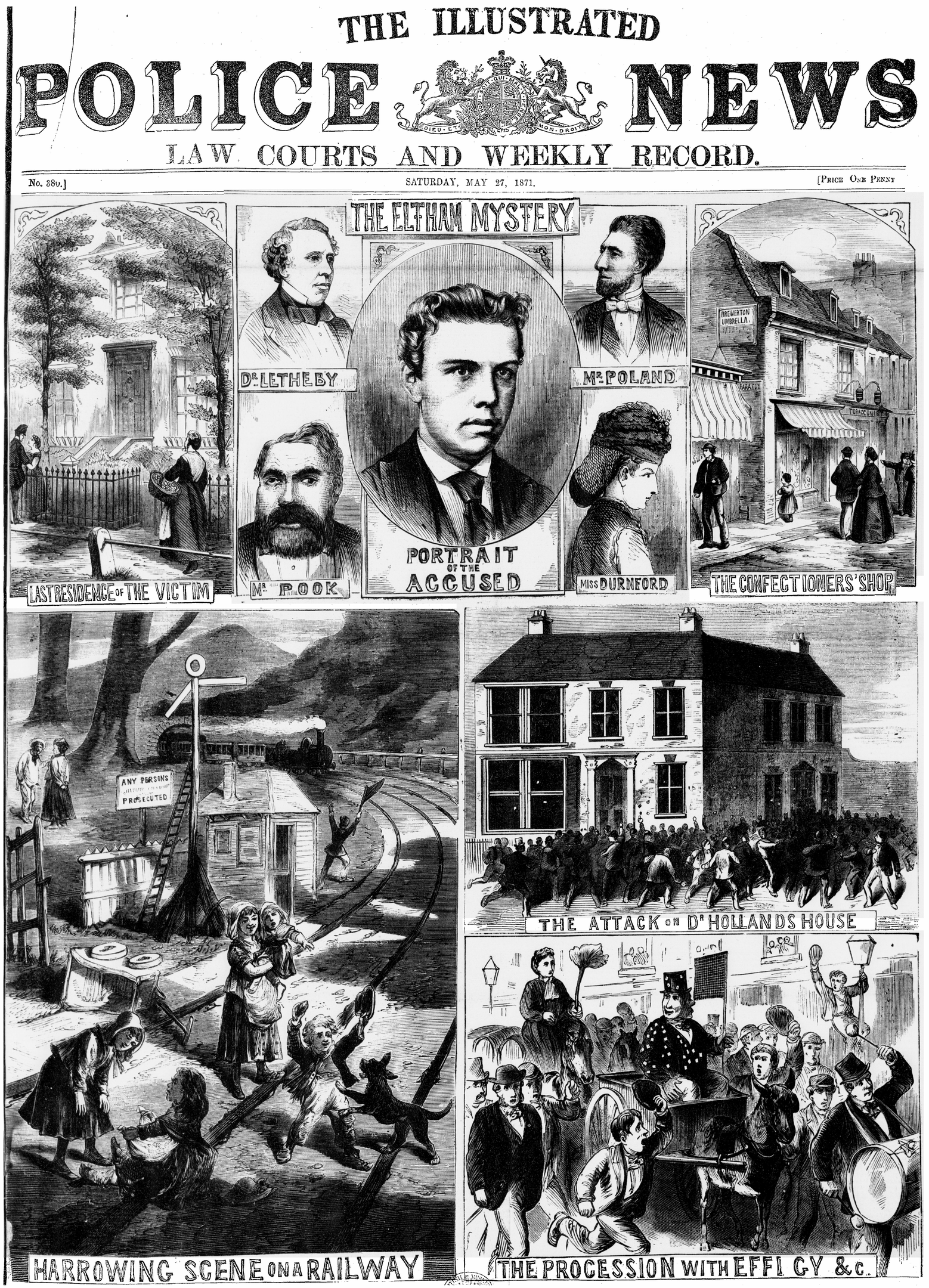

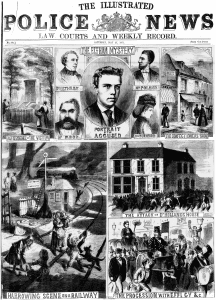

The Wilde Trial as recorded in The Illustrated Police News, May 4 1895.

Four days later, Queensberry publicly accused Wilde of sodomy by leaving a note with the porter at his club, reading “For Oscar Wilde, posing somdomite”. Despite friends’ warnings against the action, Wilde sued Queensberry for libel–a case which the author lost and which led to his arrest for “gross indecency” on April 6th, 1895.

The result led to two of the most famous trials of the century. Prosecutors presented both literary and fact-based evidence of Wilde’s homosexuality, questioning him about young men he had spent time with in London and pressing him to explain his admiration for two of Lord Alfred’s poems that had been deemed homoerotic in character.

W.B. Yeats wrote that Wilde was “the greatest talker of his time. I have never and shall never meet conversation that could match his.” Despite their tragic nature, the Wilde trials allowed for a public display of the author’s oral and rhetorical capabilities. On the stand, Wilde–like his plays–was alternately full of both sincerity and style. He responded to questions from his prosecutor, Charles Gill, with quips and one-liners that could easily have been lifted from one of his plays:

Gill: Why did you take up with these youths?

Wilde: I am a lover of youth. (Laughter.)

Gill: You exalt youth as a sort of god?

Wilde: I like to study the young in everything. There is something fascinating in youthfulness.

Gill: So you would prefer puppies to dogs and kittens to cats?

Wilde: I think so. I should enjoy, for instance, the society of a beardless, briefless barrister quite as much as that of the most accomplished Q.C. (Laughter.).

When pressed repeatedly, however, to describe “the love that dare not speak its name” in one of Lord Alfred’s poems, Wilde spontaneously issued what is perhaps the most famous–and certainly one of the most eloquent and sincere–defenses of same sex love in literary history:

‘The Love that dare not speak its name’ in this century is such a great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep, spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect. It dictates and pervades great works of art like those of Shakespeare and Michelangelo, and those two letters of mine, such as they are. It is in this century misunderstood, so much misunderstood that it may be described as the “Love that dare not speak its name,” and on account of it I am placed where I am now. It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an elder and a younger man, when the elder man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so the world does not understand. The world mocks at it and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it.

The newspaper clippings describe alternating cheers and hisses from the gallery in response to this speech, and the Judge had to demand silence and decorum in the court.

Given the overwhelming evidence mounted against him, Wilde was convicted and sentenced to two years’ hard labor in prison. Upon his release in May 1897, he fled to France and lived there on a deliberately low pittance from his wife. Due to the scandal of the trial, The Importance of Being Earnest was only performed 86 times before being cancelled, but publication of the first edition of the play in 1899 reportedly “brought Wilde a little money” while living in Paris.

Wilde died on November 30th, 1900 in poverty and exile. But his legacy, as André Gide remembers, outlived the decline of his final years:

Those who came into contact with Wilde only toward the end of his life have a poor notion, from the weakened and broken being whom the prison returned to us, of the prodigious being he was at first. It was in ’91 that I met him for the first time. Wilde had at the time what Thackeray calls ‘the chief gift of great men’: success. His gesture, his look triumphed. His success was so certain that it seemed that it preceded Wilde and that all he needed do was go forward to meet it. His books astonished, charmed. His plays were to be the talk of London. He was rich; he was tall; he was handsome; laden with good fortune and honors. Some compared him to an Asiatic Bacchus; others to some Roman emperor; others to Apollo himself — and the fact is that he was radiant.

Madeleine Joelson and Kate Clairmont are PhD students at Princeton University, studying 19th century literature.

The first edition of Wilde’s Importance of Being Earnest features in our recent catalogue, Literature in Love, a celebration of romantic love, in its ecstasy and anguish, expressed in the great stories and poetry from across the ages.