Morris on Marx

In celebration of the 200th anniversary of Karl Marx’s birth, Peter Harrington has created a special catalogue showcasing a selection of his books, alongside items pertaining to his life and work. Of particular note are first and rare editions of Das Kapital and the Communist Manifesto, as well as a an exceptional presentation copy of Das Kapital, inscribed by Marx to César De Paepe, the leader of the International Workingmen’s Association in Belgium.

Marx’s work was an inspiration to a generation of British socialists, perhaps most notable among them the poet and designer William Morris. Morris’s chief political and aesthetic motivation was a violent reaction against the ugliness and inequality of an increasingly profit-driven Victorian society, which he saw as bringing disproportionate wealth to the few whilst inflicting poverty and misery on the many. Morris first read Marx in French in 1883 (at this time Capital had yet to be translated into English and Morris knew no German). So intensely did he pour over his copy over the next year that he had to send it for rebinding to his friend and bookbinder T.J. Cobden-Sanderson, who noted later in his diary that the book ‘had been worn to loose sections by own constant study of it’. The book was rebound sumptuously in gilt-tooled green morocco. It was sold along with the rest of Morris’s library in 1898 and is now part of the collection of the Wormsley Library in Buckinghamshire.

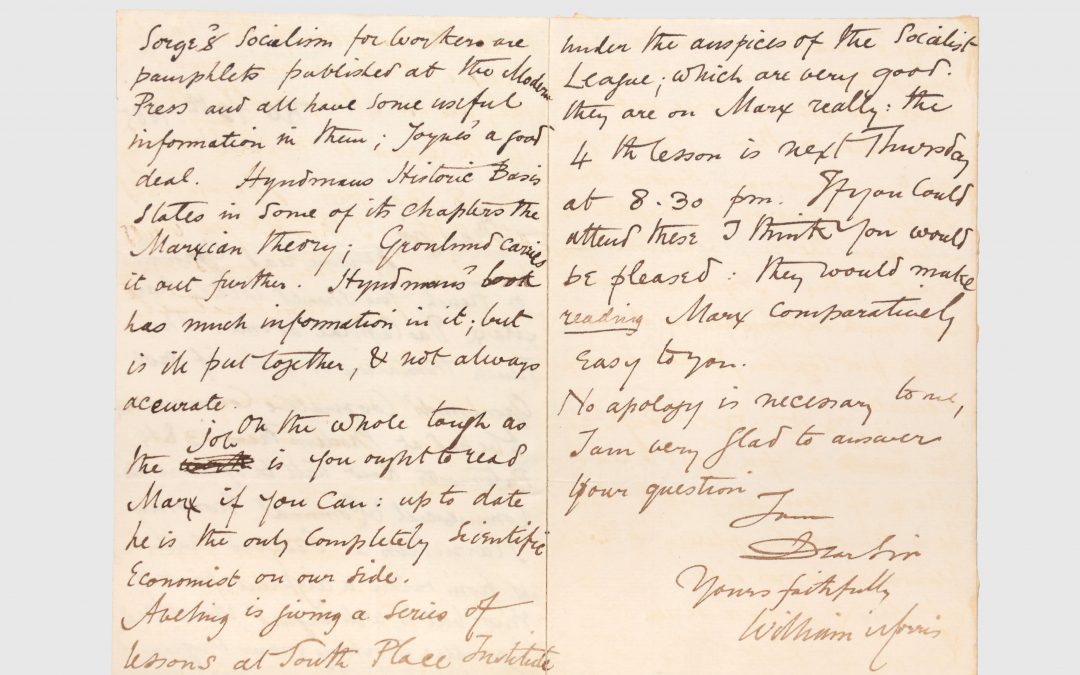

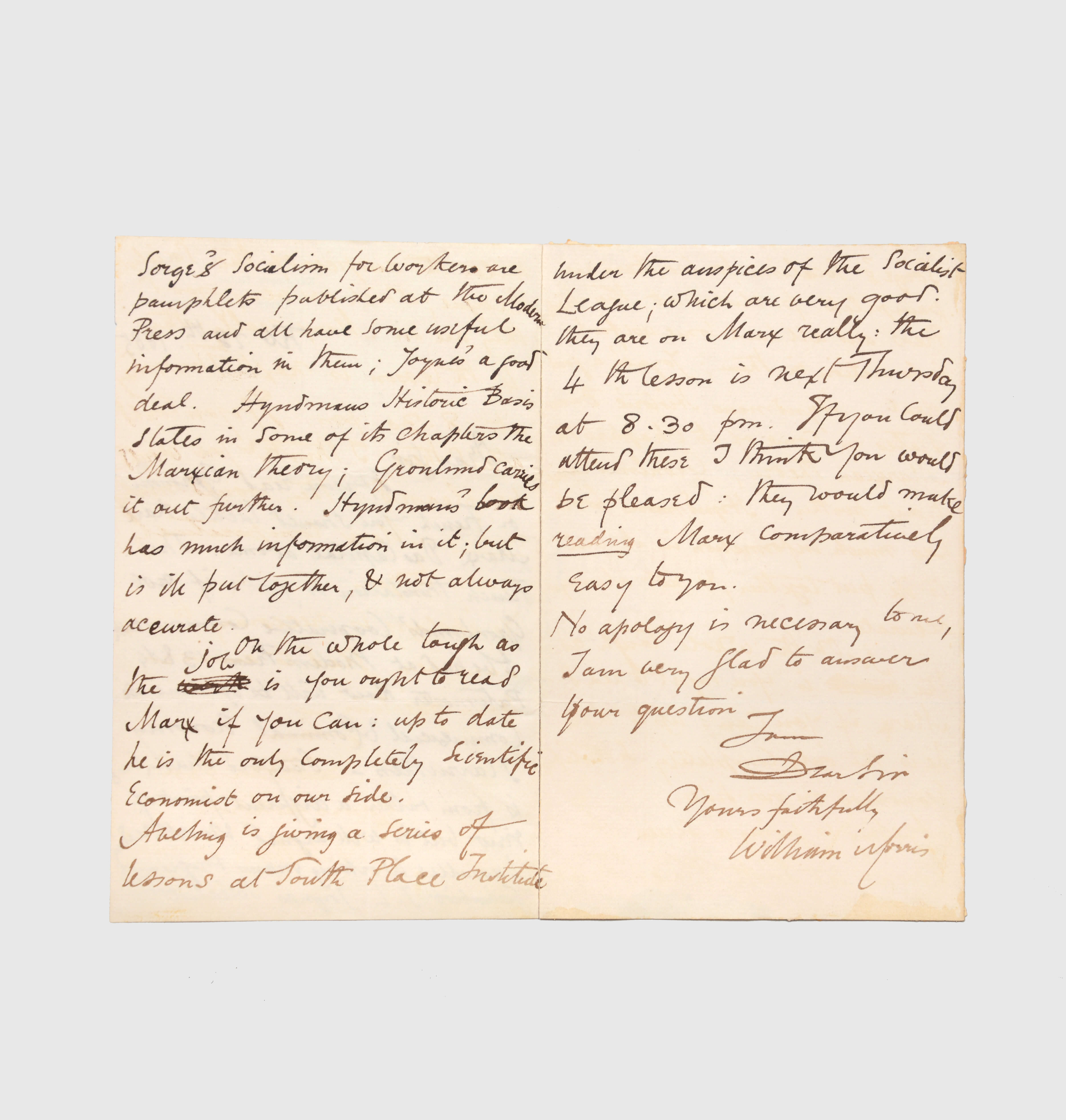

MORRIS, William. Autograph letter signed to an unknown correspondent (“Dear Sir”), recommending Marx’s Das Kapital. Kelmscott House 28 February, 1885.

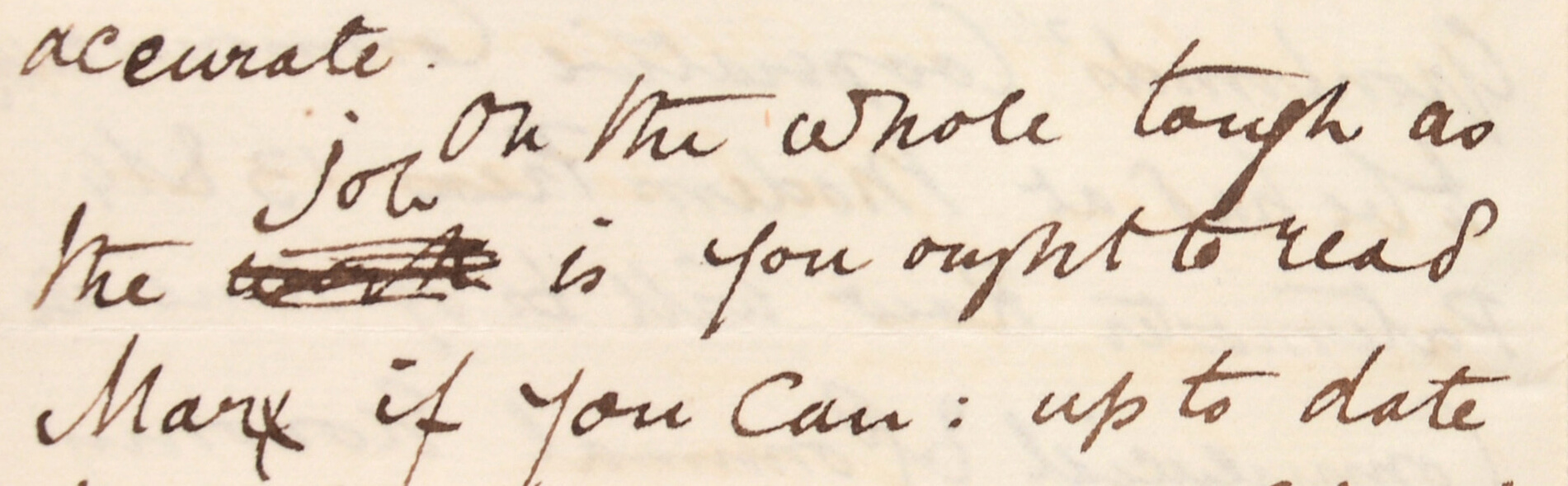

This letter, written by Morris in 1885, sheds an interesting light on his relationship with Marx. A self-taught Socialist, Morris worked hard to acquire practical knowledge about the economic and social implications of capitalism, realising that the opinions he had formulated individually were the motivations of a movement whose goal was to actively incite change. “I became a Communist before I knew anything about the history of Socialism or its immediate aims. And I had to set to work to read books decidedly distasteful to me, and to do work which I thought myself quite unfit for”, Morris recalls in his 1889 lecture about life under Socialism, ‘How Shall We Live Then?’ Indeed, his first reading of Marx caused Morris to suffer, in his own words, “agonies of confusion on the brain”, and his recommendation of Capital to his unknown correspondent in this letter – presumably someone who wished, like Morris, to gain a working knowledge of Socialism – is qualified with a reference to this difficulty. “On the whole”, he remarks, “tough as the job is you ought to read Marx if you can: up to date he is the only completely scientific economist on our side”.

You can view the full Marx anniversary catalogue here, or by clicking on the first page below.

A selection of highlights from the catalogue:

Recent Comments