Buried treasure and trouble-making: the lesser-known works of Roald Dahl

The 13th September 2016 marked the celebration of Roald Dahl 100, the one hundredth birthday of one of the best-loved children’s authors of all time. Into the lives of children all over the world, Dahl’s books have brought the joy of whizzpopping with the BFG, the voracious reading habits of Matilda, the thrill of terror at The Witches and the gluttonous imaginings of Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory. Much of the centenary celebrations have centred around these now-classic works, familiar to so many of us from our childhood reading adventures. However, the life and work of an author are rarely so clear-cut, and the various and contradictory facets of Dahl are, perhaps more so than in the case of any other author, often overlooked. To his image as the impish writer of charming children’s fiction, we might also add the dashing young airman, the historical enthusiast, the writer of James Bond scripts and the man whom his biographer Jeremy Treglown described as ‘…a bully and a self publicising trouble-maker’. Whilst you’ll find all the old favourites amongst our stock, we thought it might be nice explore the lesser-known aspects of Dahl’s work through a selection of items from our collection.

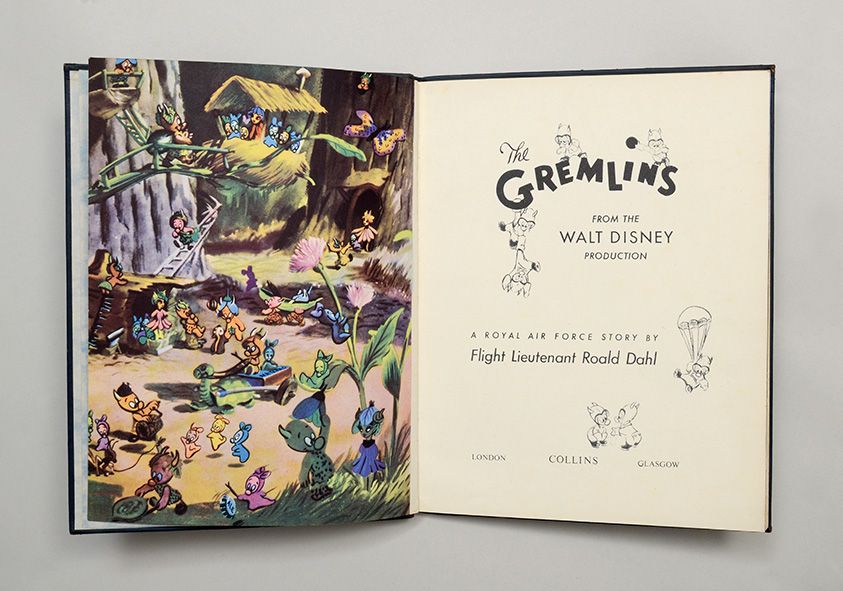

The first of Dahl’s now-iconic children’s books, James and the Giant Peach, was not published until 1961, but his first foray into children’s writing appeared almost twenty years earlier. Written whilst Dahl was working for the British Embassy in Washington DC, his story The Gremlins caught the attention of Walt Disney Productions who liked it so much that they wanted to make it into an animated feature film. The publication of the book, they hoped, would accompany the film as a promotional device.

In RAF folklore gremlins are mischievous creatures who tamper with equipment, and were often blamed for unexplained mechanical faults. It is likely that Dahl heard stories about gremlins during his time with the RAF in the Middle East: he even had his own ‘gremlins’ experience and had to perform an emergency crash landing in the Libyan Desert in 1940. In his story, the gremlins are tamed by an airman named Gus and eventually help him repair his plane and return to the air after a severe crash.

Although the Disney film ran into legal difficulties and was eventually abandoned, Dahl’s Gremlins was Published in in the US in 1943 by Random House. This edition is the first UK printing which appeared the following year and is signed by 32 assorted dignitaries, most likely at a dinner for the RAF Benevolent Fund, to whom half the royalties from the book were donated.

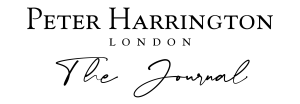

The image conjured by Dahl’s name today is, almost exclusively, that of the mischief-loving, overgrown child, dispensing sweets and chocolate and making up rude rhymes and funny words to entertain his enchanted readers. Before he became the eccentric magician of children’s fiction, however, Dahl had established a reputation as a writer of cruel and sardonic stories for adults. In her review of James and the Giant Peach in 1967, children’s author Philippa Pearce admitted trepidation at the prospect of a Dahl book for children: ‘Roald Dahl is a specialist in nightmarish narrative for adults, so that the appearance of two Dahl stories for children causes a nervous stir’ (source). Originally published in Playboy, the four stories in Switch Bitch dwell on themes of eroticism, violence and deception.

While the subject matter of these stories might be a far-cry from flying peaches or friendly giants, Dahl’s love of the absurd, the grotesque and his tendency to show a certain amount of relish in bad characters coming to sticky ends are common threads that run throughout his work, and connect his children’s writing with that intended for older readers.

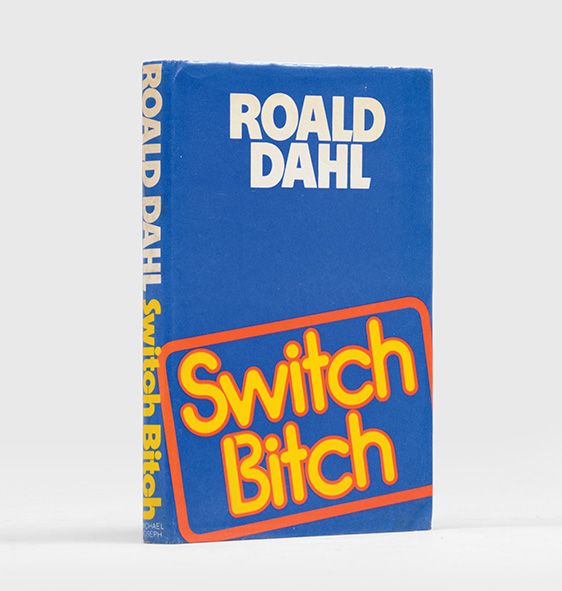

On a visit to RAF Mildenhall shortly before becoming a pilot, Dahl read a story in the paper about a hoard of Roman silver discovered by a ploughman. His imagination was captured and he made arrangements to interview Gordon Butcher, the ploughman who had uncovered the treasure, and based his narrative around Butcher’s account. Not realizing the importance of his find, Butcher had allowed his employer, Sydney Ford, to take the whole hoard away and it remained hidden in Ford’s house throughout the war years. This trove only came to light years later, when an acquaintance, a Dr Fawcett, became interested and persuaded Ford to let him take several pieces to the British Museum for analysis. Later, Ford wrote to Fawcett indignantly complaining that the police had arrived to remove the entire hoard from his ownership. A small amount of compensation for finding the treasure was eventually paid out to Ford and Butcher.

Dahl’s story originally appeared in an American publication, The Saturday Evening Post, and he sent half the money from its sale to Gordon Butcher, who wrote to Dahl ‘. . .you could have knocked me over with a feather when I saw your cheque. It was lovely. I want to thank you. . .’ The story later appeared in the collection The Wonderful World of Henry Sugar, and in this edition illustrated throughout by Ralph Steadman in 1999. Although this is supposedly a true account of the finding of the treasure, Dahl weaves his own distinctive narrative around the events. He later wrote that his account may not have been altogether accurate, but that this didn’t worry him in the least. Dahl’s story of a stoic Suffolk ploughman unearthing this fabulous treasure in a lonely, windswept field remains one of the ways many people have heard of the Mildenhall silver, and has tempted not a few to see it for themselves at the British Museum, where it remains to this day.

If you would like to make an enquiry about selling a book or about the value of an item you own, please fill out the form which can be found here.

![DAHL, Roald. The Gremlins. From the Walt Disney Production. A Royal Air Force Story DAHL, Roald. The Gremlins. From the Walt Disney Production. A Royal Air Force Story. [1944] £12,500](https://www.peterharrington.co.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/83206_2.jpg)

Recent Comments