From Page to Stage

Live theatre is, by its very nature, transient. It is experienced by an audience on a specific evening and, after the curtain falls, it is only the memory of the performance that remains. Or is it?

In this blog I’d like to look at a few special scripts that are textual witnesses to the changes that happen during rehearsal. They help provide a context or evidence for this most ephemeral of short-lived spectacles.

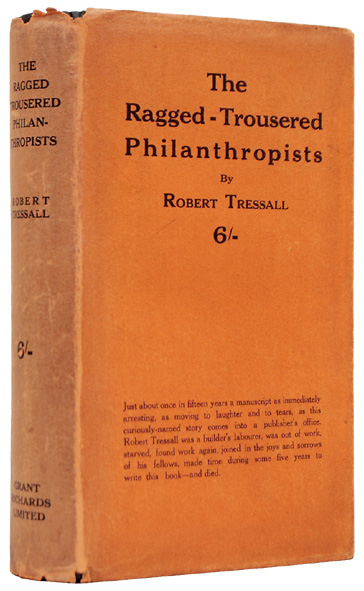

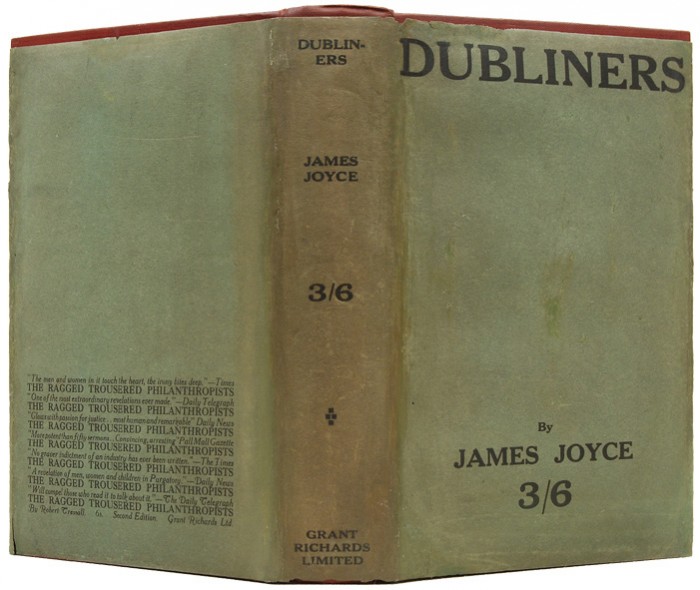

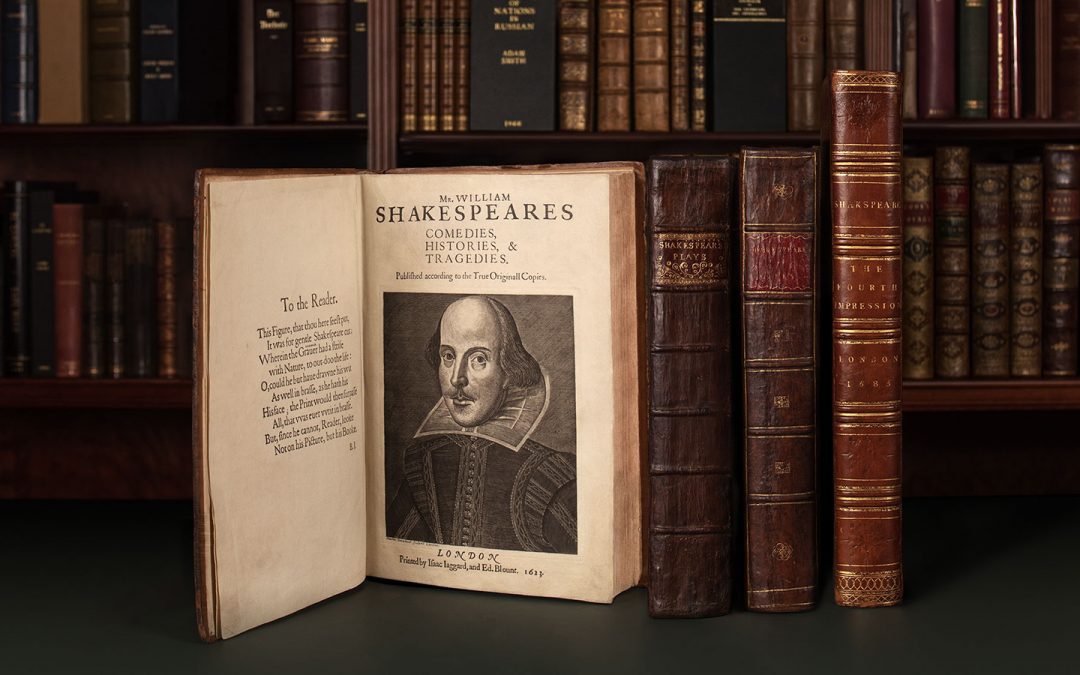

But, first, let’s take a very quick look at other types of source material. Most stage shows are based on something else. Shakespeare plundering the chronicles of Holinshed is well-known. As are sources for musicals. There should be no prizes for knowing the inspiration behind Bart’s Oliver!, Minchin’s Matilda, Boublil and Schonberg’s Les Misérables, or Loesser’s Guys & Dolls. With a few obvious exceptions, however, it’s rare to find a hugely successful adaptation of an extremely well-known book. There have, for example, been musical versions of Jane Eyre, Frankenstein, The Lord of the Rings, and Robinson Crusoe. But they’ve rarely been palpable hits. On the other hand, Fiddler on the Roof is far better-known than the source stories by Sholem Aleichem. I’d also suggest that more people are familiar with The Sound of Music than The Story of the Trapp Family Singers, or The King and I than Anna and the King of Siam. There are, naturally, plenty of musicals based on films, or jukebox musicals which have no book source. There are musicals based on comic strips (The Addams Family, Annie and, my personal favourite, Snoopy! The Musical) or true events, or biographies, or plays, or a vast number of other sources. My point is that, within the book world, there are excellent opportunities to assemble a collection of interesting source texts that have significant interest as books in their own right.

How source material has been developed and transformed from page to stage provides many insights into the creative process. But once that process has started, to what extent can we chart or understand this development? It’s at this point that original scripts become important.

At Peter Harrington, we are privileged to be handling some scripts from the significant theatre collection of Clive Hirschhorn, the distinguished film and theatre critic for the Sunday Express and whose histories of the film industry include The Warner Bros (1978) and The Hollywood Musical (1981). The collection includes a number of rehearsal scripts used during the creative process and these provide a fascinating insight into the development of some exceptional productions.

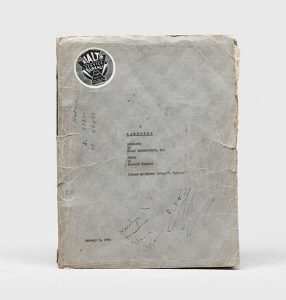

A working rehearsal script for West Side Story was once owned by Mickey Calin, who created the role of Riff. It’s a fascinating combination of carbon and mimeographed leaves and suggests that changes to the script were distributed in carbon copies to appropriate members of the cast (to replace mimeographed pages). The text was seemingly being revised throughout rehearsals. In all, this copy has 27 different sections in either carbon or mimeograph. One section, Act 1, scene 2, is represented twice. One part, Act 1, scene 8, is not represented at all (beyond a title). It is significant that the musical numbers are indicated within the script, but that the lyrics are not present. The songs “America”, “Maria”, and “I feel pretty” are named, but the opening number “When you’re a Jet” is simply introduced as “Riff sings first chorus of song”. Elsewhere there are a large number of changes to the text for the character of Schrank (Officer Krupke’s sidekick), suggesting that ownership of this script changed during the rehearsal period. Intriguing notes also include a few snatches of “America” with “Puerto Rico, you lovely island / Island in the tropic breezes”. This is not exactly the version that survived to the opening night. Given that Clive Hirschhorn worked within the theatre industry, he frequently had an opportunity to acquire an interesting signature or inscription. This script is no exception. It is inscribed by the author of the “book”, “To Clive Hirschhorn, Best wishes, Arthur Laurents, 4/21/99” and the lyricist has provided an inscription using Clive’s occasional pseudonym, “To Clive Errol, Stephen Sondheim, 4/24/98”.

A working rehearsal script for West Side Story was once owned by Mickey Calin, who created the role of Riff. It’s a fascinating combination of carbon and mimeographed leaves and suggests that changes to the script were distributed in carbon copies to appropriate members of the cast (to replace mimeographed pages). The text was seemingly being revised throughout rehearsals. In all, this copy has 27 different sections in either carbon or mimeograph. One section, Act 1, scene 2, is represented twice. One part, Act 1, scene 8, is not represented at all (beyond a title). It is significant that the musical numbers are indicated within the script, but that the lyrics are not present. The songs “America”, “Maria”, and “I feel pretty” are named, but the opening number “When you’re a Jet” is simply introduced as “Riff sings first chorus of song”. Elsewhere there are a large number of changes to the text for the character of Schrank (Officer Krupke’s sidekick), suggesting that ownership of this script changed during the rehearsal period. Intriguing notes also include a few snatches of “America” with “Puerto Rico, you lovely island / Island in the tropic breezes”. This is not exactly the version that survived to the opening night. Given that Clive Hirschhorn worked within the theatre industry, he frequently had an opportunity to acquire an interesting signature or inscription. This script is no exception. It is inscribed by the author of the “book”, “To Clive Hirschhorn, Best wishes, Arthur Laurents, 4/21/99” and the lyricist has provided an inscription using Clive’s occasional pseudonym, “To Clive Errol, Stephen Sondheim, 4/24/98”.

If West Side Story changed the Broadway musical in the late-1950s, it was the partnership of Rodgers and Hammerstein who first started to shake things up in the mid-1940s. Oklahoma! is generally remembered as a musical in which musical songs are integrated into the action to advance the plot (compared with stand-alone numbers which did nothing for the narrative). It was in Carousel, their second musical, in which this was further developed. The courtship of Billy Bigelow and Julie Jordan is one of the longest in any Broadway show and through dialogue, underscore and song the story advances in a new and stunning way. It is therefore exciting to have the rehearsal script owned by Jan Clayton, the creator of the role of Julie, and see a small change in her dialogue in this scene. The line as present on the mimeographed script is “I like to watch the moon upon the sea”. This has been changed by hand to “To watch the moon come closer to the sea”. A significant revision is the scene when Billy dies and is received into Heaven by the characters of “He” and “She”. It was a scene that caused Rodgers and Hammerstein considerable difficulty. Rodgers would later refer to the characters as “Mr and Mrs God” and the general feeling was that the scene didn’t work. It was cut and a replacement character, the Star-Keeper, created. The original scene is, however, contained in the present script.

If West Side Story changed the Broadway musical in the late-1950s, it was the partnership of Rodgers and Hammerstein who first started to shake things up in the mid-1940s. Oklahoma! is generally remembered as a musical in which musical songs are integrated into the action to advance the plot (compared with stand-alone numbers which did nothing for the narrative). It was in Carousel, their second musical, in which this was further developed. The courtship of Billy Bigelow and Julie Jordan is one of the longest in any Broadway show and through dialogue, underscore and song the story advances in a new and stunning way. It is therefore exciting to have the rehearsal script owned by Jan Clayton, the creator of the role of Julie, and see a small change in her dialogue in this scene. The line as present on the mimeographed script is “I like to watch the moon upon the sea”. This has been changed by hand to “To watch the moon come closer to the sea”. A significant revision is the scene when Billy dies and is received into Heaven by the characters of “He” and “She”. It was a scene that caused Rodgers and Hammerstein considerable difficulty. Rodgers would later refer to the characters as “Mr and Mrs God” and the general feeling was that the scene didn’t work. It was cut and a replacement character, the Star-Keeper, created. The original scene is, however, contained in the present script.

When the original owner, Jan Clayton, left the cast for another show, she evidently asked some of her fellow cast members to inscribe her script. She was, evidently, going to be missed. Inscriptions include “Dear Jan, I wish the west could send us more leading ladies like you. Everyone in the company loves you and how we’ll miss you – But, we are wishing you all the success in the world in Show Boat and then on and on and on and on” and “Some replacements are ok – but you are Julie”.

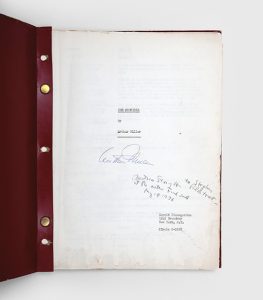

Turning to plays, the Hirschhorn Collection includes a rehearsal script of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, formerly owned by Beatrice Straight who created and won a Tony Award for the role of Elizabeth Proctor. Set during the Salem witch trials of the 1690s, The Crucible was a thinly-veiled attack on the persecution of left-wing individuals in the US, known as McCarthyism. The play won the 1953 Tony Award for “Best Play” (and therefore made Miller the first recipient of two Tony Awards in this category). It opened on Broadway on 22 January 1953 starring Arthur Kennedy as John Proctor, Walter Hampden as Deputy-Governor Danforth, E. G. Marshall as Reverend John Hale, Madeleine Sherwood as Abigail Williams, and Beatrice Straight. During the run, Miller revised the piece and added a brief scene between Abigail Williams and John Proctor that motivated their clash in the following court room scene. The present script appears to represent the text in this revised version. It differs, however, from the version published by the Viking Press in April 1953. Miller’s published edition is aimed at readers, not actors. There are lengthy descriptions of characters which would be out of place in a rehearsal script. Of significance are very precise staging directions in the present script, later changed for publication. The rehearsal script is also provided with stresses indicated by underlining to certain words. These stresses are abandoned for the published version. The script is signed by the author on the title page.

Turning to plays, the Hirschhorn Collection includes a rehearsal script of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, formerly owned by Beatrice Straight who created and won a Tony Award for the role of Elizabeth Proctor. Set during the Salem witch trials of the 1690s, The Crucible was a thinly-veiled attack on the persecution of left-wing individuals in the US, known as McCarthyism. The play won the 1953 Tony Award for “Best Play” (and therefore made Miller the first recipient of two Tony Awards in this category). It opened on Broadway on 22 January 1953 starring Arthur Kennedy as John Proctor, Walter Hampden as Deputy-Governor Danforth, E. G. Marshall as Reverend John Hale, Madeleine Sherwood as Abigail Williams, and Beatrice Straight. During the run, Miller revised the piece and added a brief scene between Abigail Williams and John Proctor that motivated their clash in the following court room scene. The present script appears to represent the text in this revised version. It differs, however, from the version published by the Viking Press in April 1953. Miller’s published edition is aimed at readers, not actors. There are lengthy descriptions of characters which would be out of place in a rehearsal script. Of significance are very precise staging directions in the present script, later changed for publication. The rehearsal script is also provided with stresses indicated by underlining to certain words. These stresses are abandoned for the published version. The script is signed by the author on the title page.

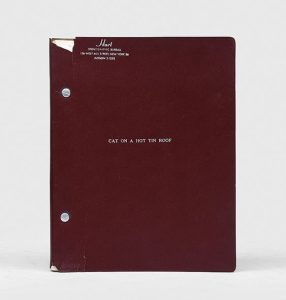

Another hugely important American play from the 1950s is Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. The work would win Williams his second Pulitzer Prize and the version in the Hirschhorn Collection is a rehearsal script for the pre-Broadway tryout in Philadelphia. An academic research paper, published in 1996, entitled “A Preliminary Stemma for Drafts and Revisions of Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” noted that one task in Williams scholarship (and “perhaps the most daunting of all”) is “to collate, put into sequence, and analyse the… drafts and revisions that lie behind… Williams’s published work”. The present script is one of those drafts and includes two aspects omitted in later versions. These comprise an episode in which Big Daddy sensually touches Maggie’s stomach to determine if she’s pregnant, and Brick’s admittance that “I might be — impotent”. In the present script, Margaret’s last speech, in which she makes reference to a cat on a tin roof, is longer than the published version.

Another hugely important American play from the 1950s is Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. The work would win Williams his second Pulitzer Prize and the version in the Hirschhorn Collection is a rehearsal script for the pre-Broadway tryout in Philadelphia. An academic research paper, published in 1996, entitled “A Preliminary Stemma for Drafts and Revisions of Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” noted that one task in Williams scholarship (and “perhaps the most daunting of all”) is “to collate, put into sequence, and analyse the… drafts and revisions that lie behind… Williams’s published work”. The present script is one of those drafts and includes two aspects omitted in later versions. These comprise an episode in which Big Daddy sensually touches Maggie’s stomach to determine if she’s pregnant, and Brick’s admittance that “I might be — impotent”. In the present script, Margaret’s last speech, in which she makes reference to a cat on a tin roof, is longer than the published version.

The transition from page to stage is a process that includes a large number of talented individuals and can create a wonderful experience in the theatre. The scripts that originate from rehearsals can help us understand something of the creative process and provide a fascinating insight into this most transient of creations.

Dr Phil Errington, Senior Specialist, has been known to indulge in amateur dramatics. From Gilbert and Sullivan to Sondheim, roles include Scrooge to Prince Charming!

Recent Comments