The Origin of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol

It may be the most loved Christmas Story ever written. Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol was a bestseller when it was published in 1843, and has never been out of print. It has inspired hundreds of stage and film adaptations and has influenced the way people around the world view Christmas. Dickens wrote four other Christmas books in the years following, yet none of them had the same impact. What makes A Christmas Carol so special?

In February of 1843, Charles Dickens and his friend the Baroness Burdett-Coutts became interested in the Ragged Schools, a system of religiously-inspired schools for the poorest children in Britain. Bourdett-Coutts had been asked donate to them, and she requested that Dickens visit the school at Saffron Hill and report back to her. The author, having experienced poverty and child labour himself, was deeply concerned with its elimination, and believed that education was an important way to achieve this. But he was shocked by what he saw at Saffron Hill. “I have seldom seen”, he wrote to Bourdett-Coutts, “in all the strange and dreadful things I have seen in London and elsewhere, anything so shocking as the dire neglect of soul and body exhibited in these children” (Mackenzie, Dickens, pp. 143-44).

All that year the Saffron Hill children stayed in Dickens’ mind, and he briefly considered writing a journalistic piece on their plight. Then in October, while visiting a workingmen’s educational institute in Manchester, he suddenly thought of a way to address in fiction his concerns about poverty & greed, and A Christmas Carol was born. Once back in London, Dickens began writing “at a white heat” (ODNB), telling his friend Cornelius Felton that while composing he “wept and laughed and wept again, and excited himself in a most extraordinary manner… and thinking whereof he walked about the black streets of London, fifteen and twenty miles many a night when all the sober folks had gone to bed” (Letters of Charles Dickens, Macmillan & Co., 1893, pp. 101-02).

It was a deeply personal and cathartic experience. Though Dickens hoped to elicit concern for poor children, represented in the story by Tiny Tim, he also wrote from a darker place. He had grown up poor and was still acutely conscious of money, never feeling comfortable that he had enough (one of the reasons he wrote A Christmas Carol was to increase his earnings during a slow period). And yet he distrusted the instinct to hoard it, and donated much to the needy. It was from these anxieties that he created Ebenezer Scrooge, one of the greatest examples of redemption in all of literature, with a life story remarkably similar to Dickens’. Scrooge is Dickens imagining “what he once was and what he might have become” (Ackroyd, Dickens, p. 412).

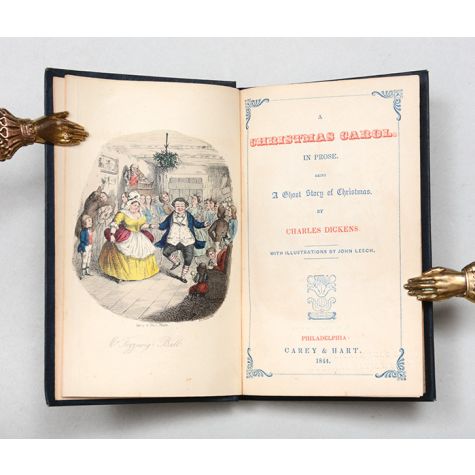

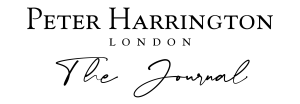

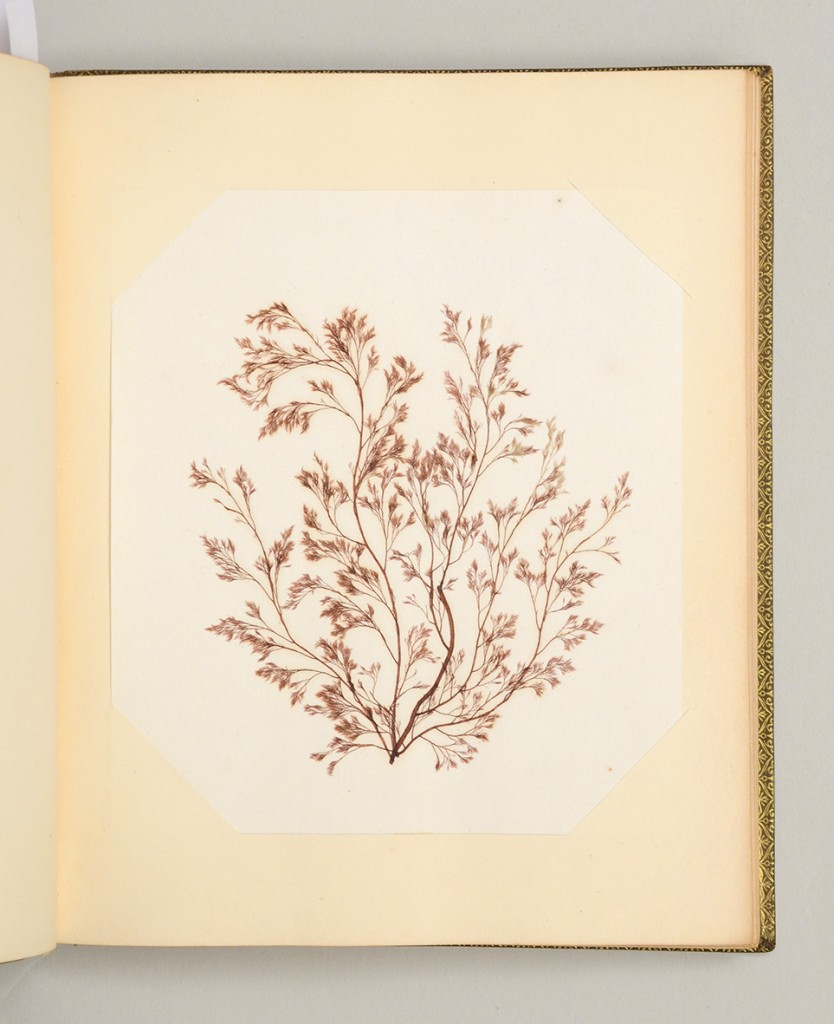

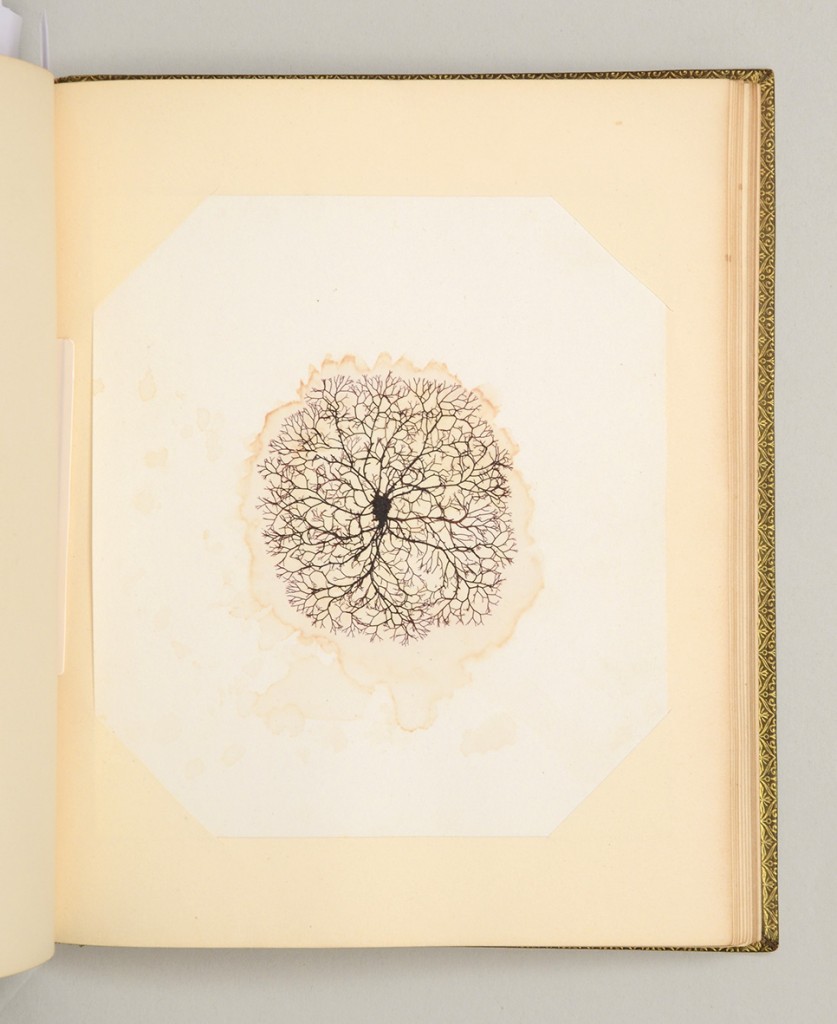

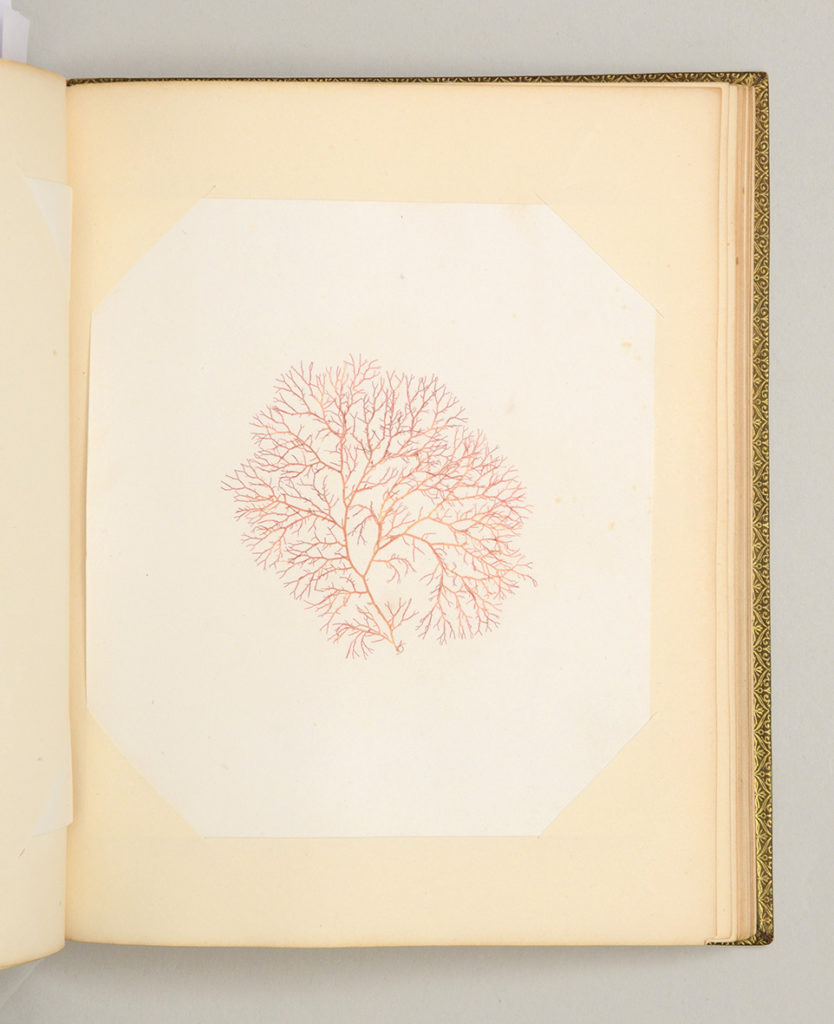

Dickens finished writing in only six weeks, though he was also working on Martin Chuzzlewit, and celebrated “like a madman” (Letters, p. 102). He arranged with Chapman & Hall to publish the story on a commission basis, giving him the freedom to design the book to his own high standards. Bound in pinkish-brown cloth, it included elaborate gilt designs on the cover and spine, as well as gilt edges, hand-coloured green endpapers (which were later changed to yellow because the green tended to rub off), four coloured etchings, and four uncoloured engravings. Despite the expense of printing and binding such a volume, the price was set at a low five shillings, which contributed to its popularity.

As soon as it appeared, A Christmas Carol was “a sensational success… greeted with almost universal delight” (ODNB). William Makepeace Thackeray called it, “a national benefit and to every man or woman who reads it a personal kindness” (Fraser’s Magazine, February 1844). Published only a week before Christmas, six thousand copies sold by Christmas Eve, with sales continuing into the New Year and a pirated edition also selling briskly, much to Dickens’ dismay.

A Christmas Carol struck such a chord because it was informed by Dickens’ own troubled life, his ambivalence toward the wealth he was accruing as a successful author, and his deeply held beliefs about goodness, charity, and the sin of institutionalized poverty. His skill as an author was drawing from the world around him, and from within himself, universal themes that have resonated with millions of readers across the years. Indeed, there seems to be something for almost everyone, at every time, in this little book. As the novelist and biographer Peter Ackroyd put it,

A Christmas Carol takes its place among other pieces of radical literature in the same period… But clearly, too, there are many religious motifs which give the book its particular seasonal spirit; not only the Christmas of parties and dancing but also the Christmas of mercy and love… But it combined all these things within a narrative which has all the fancy of a fairy tale and all the vigor of a Dickensian narrative. There was instruction for those who wished to find it at the time of this religious festival, but there was also enough entertainment to render it perfect ‘holiday reading’; it is rather as if Dickens had rewritten a religious tract and filled it both with his own memories and with all the concerns of the period. He had, in other words, created a modern fairy story. And so it has remained. (Ackroyd, p. 413.)

- Click here for our complete selection of books by Charles Dickens. For our contact information, click here.

- For more on Charles Dickens, see our recent blog post on the first editions of Charles Dickens.

- The two biographies consulted for this piece are Dickens: A Life by Norman and Jeanne MacKenzie, and Dickens by Peter Ackroyd, as well as The Letters of Charles Dickens published by MacMillan in 1893.

- There are many great YouTube clips from film versions of A Christmas Carol. Here’s Patrick Stewart in his acclaimed role as Scrooge, in this scene meeting Marley’s ghost for the first time. And, wonderfully, the 1935 film starring Seymour Hicks is available in its entirety.

Recent Comments