“A singularly forbidding woman” – the life of May Morris

William Morris looms large in British literary history, for his own writing, his politics, and his radical impact on others. His birth on 24 March 1834 was followed exactly 28 years and 1 day later by that of his second daughter, Mary “May” Morris on 25 March 1862. Every bit the pioneer, activist, and tumultuous personality as her father, in this blog we celebrate both their birthdays by exploring May’s life and legacy.

May grew up in the very heart of the arts and crafts movement. The dignitaries of the set regularly visited the Morris family, first in their Red House in Kent, where Morris & Co. was first founded, and then from 1865 in No. 26 Queen Square, Bloomsbury: the family’s flat directly above “the Firm’s” shop. Growing up in such an environment, and largely educated at home, May was immersed in the contemporary literary and artistic milieu, occasionally startling guests with her seemingly precocious desire to join conversations, and often modelling for Edward Burne-Jones, regular visitor Gabriel Dante Rossetti, and artist George Howard.

In 1881, May enrolled at the National Art Training School in Kensington (later the Royal College of Art) and chose embroidery as her field of study, having been trained in the art by her mother, Jane Morris, from a young age. In 1883, she designed one of Morris & Co.’s most popular pattern designs – ‘Honeysuckle’, followed by the equally enduring ‘Horn Poppy’ in 1885. May was given responsibility for the embroidery operations of Morris & Co in 1885, when she was just 23 years old. She took this on directly from Jane, who led the department herself for over 20 years. She regularly took part in Arts & Crafts exhibitions from 1888 onwards, gaining renown for her designs and skill.

Angered by the lack of support for the women practitioners she saw around her, despite the proliferation of influential women in the movement, she founded the Women’s Guild of Arts in 1907, with fellow embroiderer Mary Elizabeth Turner. Their aim was to create an “atmosphere of camaraderie” through meetings, exhibitions, and training. May was an active teacher, at the Royal School of Art Needlework, the Birmingham, Leicester, and Hammersmith art schools, and the London County Council School of Art, where she was head of the embroidery department from 1899 until 1905. In 1893, she published a definitive thesis on embroidery, Decorative Needlework, which is still referenced today. In the work she recommends carefully using simple stitches over attempting difficult needlework, and states that “the most important element in successful work is the choice of design” (Morris, p. 79). She suggests that “inferior work can be tolerated for the sake of the design” but “excellent work on a worthless design must be cast aside as labour lost” (Morris, p. 79).

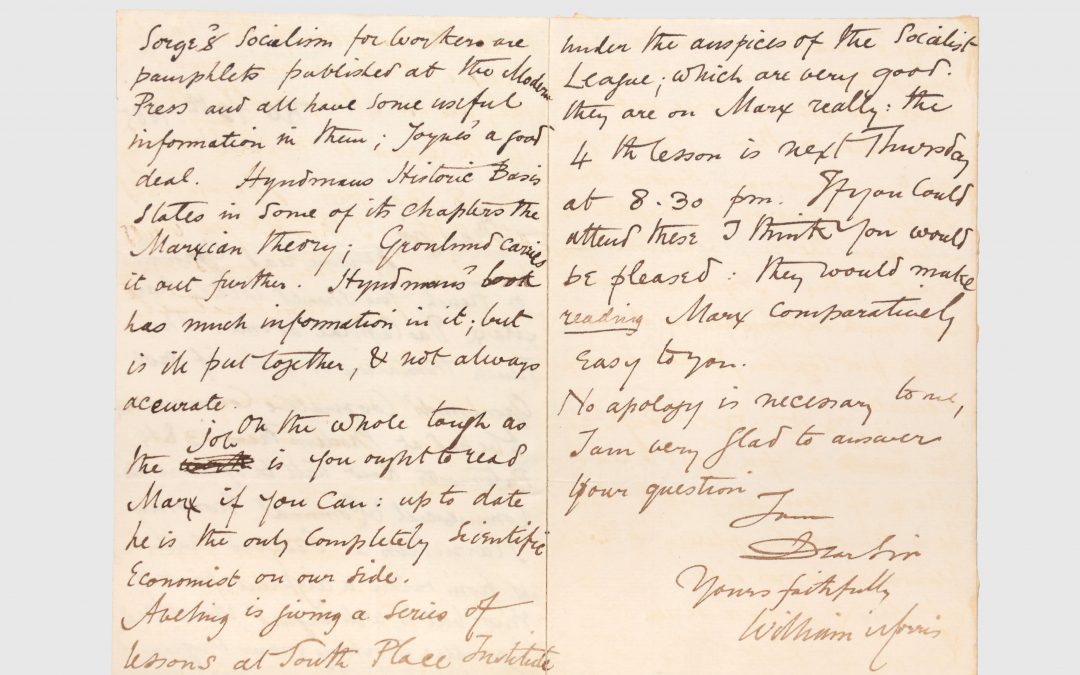

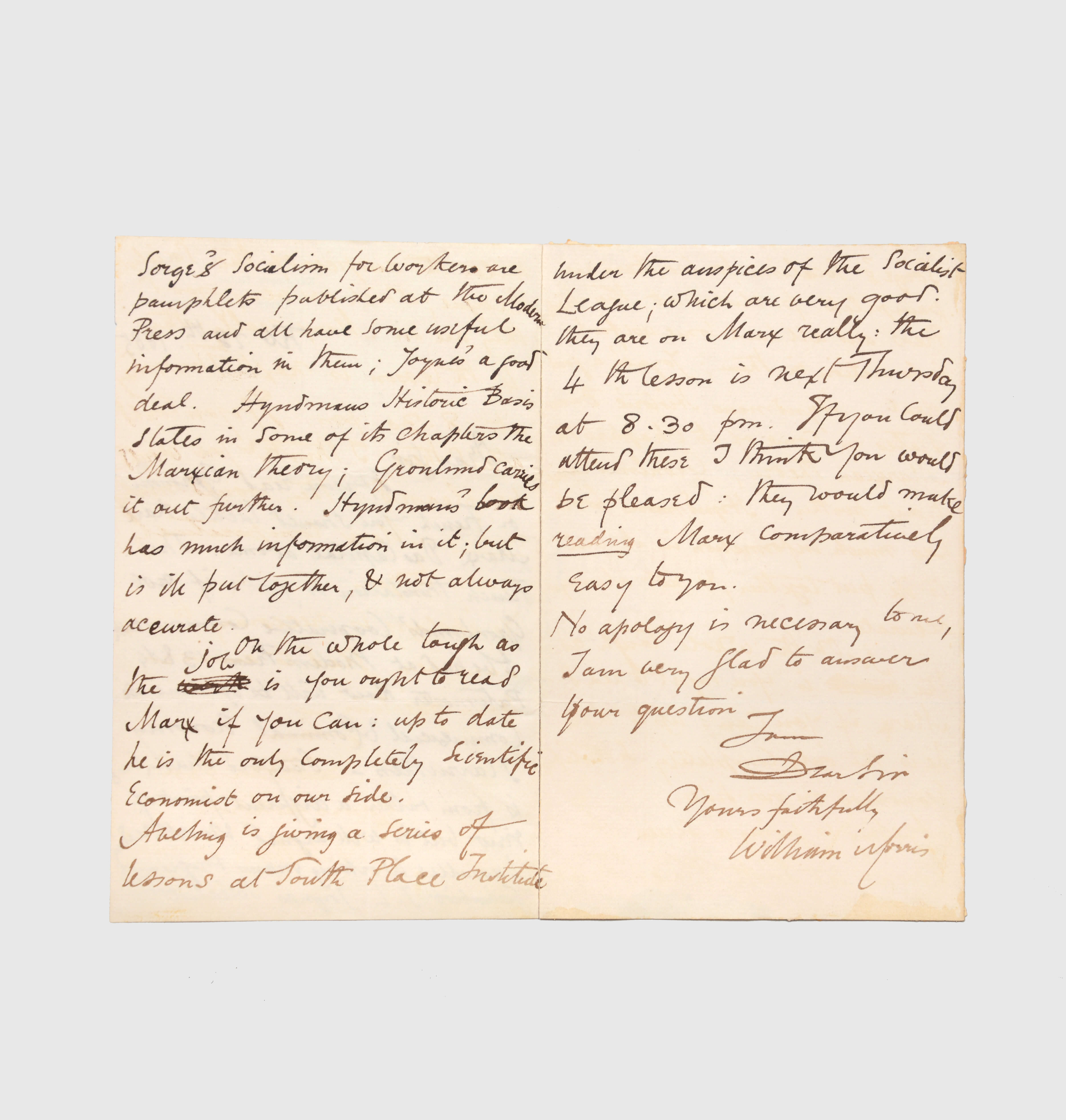

An avid socialist, May joined the Social Democratic Federation in 1884, in which her father was already active. By the end of the year father and daughter were key in the break from the Federation and the consequent formation of the Socialist League, for which she ran the library. May developed a close friendship with fellow founder Eleanor Marx based upon their politics and love of the plays of Henry Ibsen, and the two regularly acted in the socialist plays the League put on to raise funds. William Morris attended at least one such performance: in January 1885 he was in the audience when May appeared with Eleanor and George Bernard Shaw in the comic drama Alone by Palgrave Simpson and Herman Merivale. William Morris was famously never a fan of the theatre: May wrote that those who accompanied him sat in “terror as to whether his muttered exclamations could be heard right or left” mingled “with a certain high glee over the picturesqueness of his unmanageable playgoer’s comments” (Morris, p. xxviii). May herself took to the world of drama, writing and publishing two plays: Lady Griselda’s Dream, published in Longman’s Magazine in June 1898 and White Lies: A Play in One Act, privately published by the Chiswick Press in 1903.

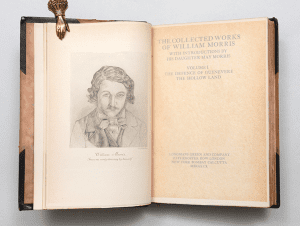

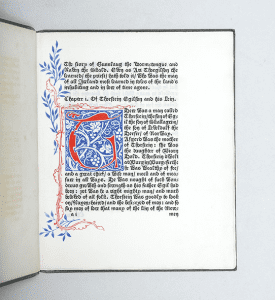

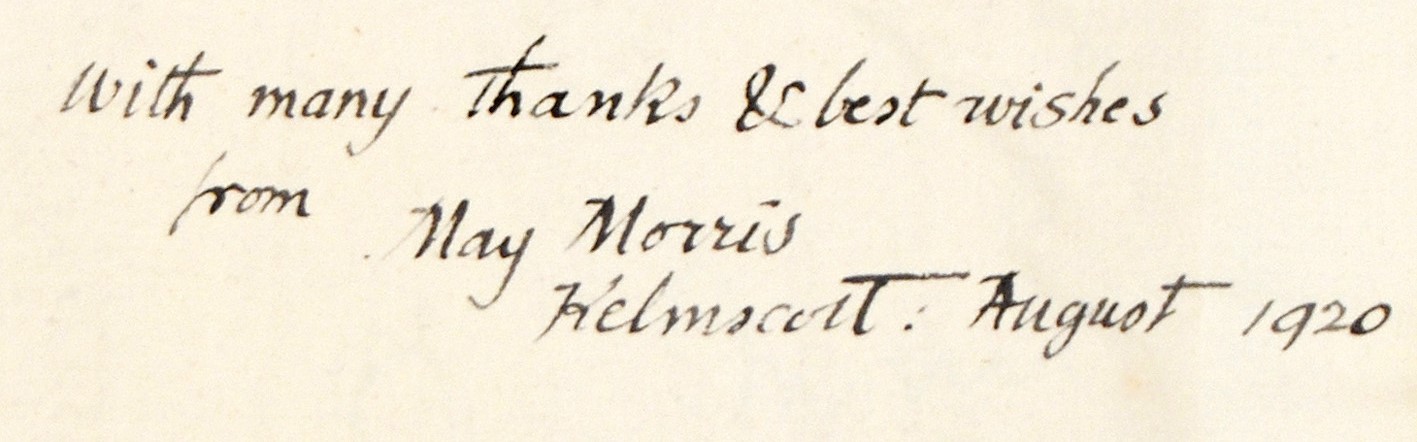

Following William Morris’s death in October 1896 May worked tirelessly on publishing his collected works, which amounted to 24 volumes of his literary, artistic, and political writings, each with her introduction. These introductions were themselves so detailed and copious that they have been published separately, in 1973, in their own two volume set. The Collected Works were published by Longmans Green and Co. between 1910 and 1915, and were followed in 1936 by a supplementary work, William Morris: Artist, Writer, Socialist, rejected by Longmans on economic grounds and consequently published by Basil Blackwell. Two of the volumes constitute the first editions of the text: Scenes from the Fall of Troy and Other Poems, issued as volume 24, and Journals of Travel in Iceland in 1871 and 1873, issued as volume 8.

William Morris’s love of Iceland is no secret: his own writing was hugely influenced by the medieval sagas and poetry of Iceland, in particular his long poems “The Lovers of Gudrun” and Sigurd the Volsung. Between 1868 and 1876 he translated several major Icelandic sagas into English for the first time with his collaborator Eiríkur Magnússon. He visited the island twice, in 1871 and 1873, travelling the interior on horseback. In the summer of 1924, May followed in her father’s footsteps, travelling to Iceland with her partner Mary Frances Vivian Lobb, returning again in 1926 and 1931. In Iceland, May built a wide network of friends, promoted the country‘s medieval literary inheritance, and donated 400 books to the library in Húsavik. In June 1930 she was awarded the Order of the Falcon by the Icelandic Government for her championing of their literary heritage in England, and for her advocacy in English newspapers for the 1,000th anniversary of the ancient Icelandic parliament.

Kelmscott Manor, which the family had rented since 1871 and bought in 1913, passed to May in 1914, and she moved there permanently in 1923. Mary Lobb (1878-1939) first came into May’s life as member of the local Land Army, put to work near Kelmscott Manor in 1917. Having been fired from the land army (accounts suggest she was so foul-mouthed that it became imperative she work alone) Mary joined the Kelmscott household as a gardener, and became a lifelong companion to May. She died in the Spring of 1939, just a few months after May’s own death in 1938. While the particulars of any relationship are only known to those involved and are subject to the vocabulary and social norms of any given era, contemporaries regularly commented on the joy their relationship brought one another, as well as speculating on its nature. The two women were active partners in their public as well as personal lives. Both became leading figures in the local Women’s Institute, and the two worked together on May’s commission of a pair of cottages in Jane’s memory, one of which was to be the village school-house, as well as a Village Hall, which was completed in 1934 and opened by George Bernard Shaw.

As much a polymath and influential artistic figure as her father, May was described by Evelyn Waugh in his diary entry for 6 October 1927 as “a singularly forbidding woman … dressed in a slipshod ramshackle way in hand-woven stuffs” (Waugh, p. 291). Undoubtedly true, she was also, as she states in her own words “a remarkable woman, always was, though none of you seemed to think so” (May Morris, 1936, letter to George Bernard Shaw).

Written by Suzanna Beaupré, Rare Book Specialist

Bibliography

May Morris (ed.), The Collected Works of William Morris, XXII, Longmans, Green & Co. 1910-15.

Evelyn Waugh, The Diaries of Evelyn Waugh, 1976.

Recent Comments