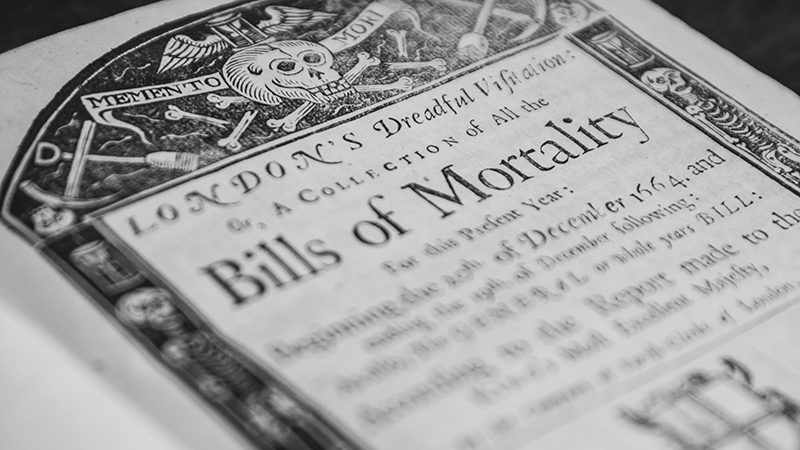

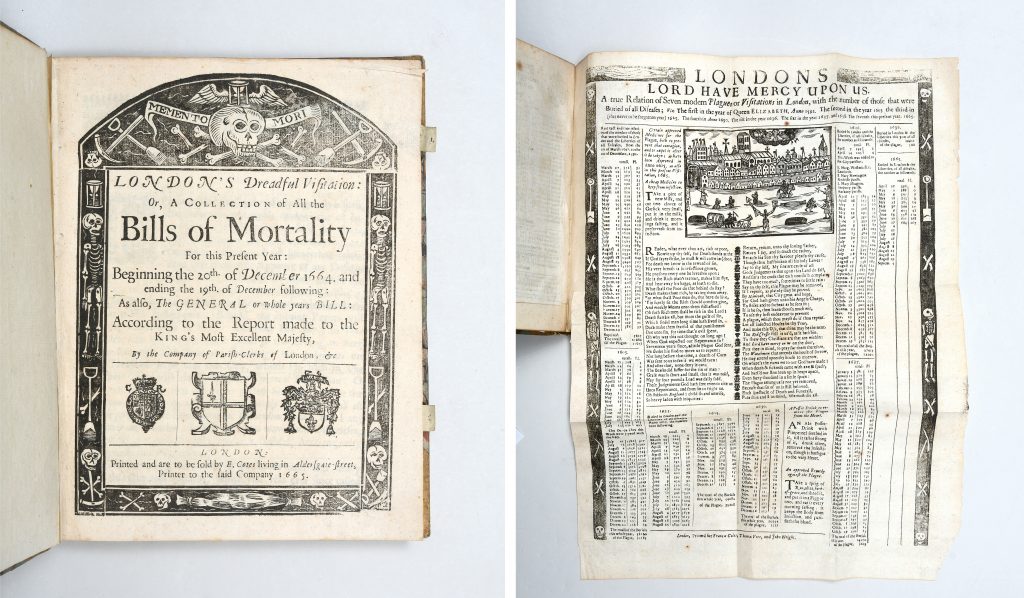

Comprised of information collected by knowledgeable local women known as Searchers, and printed by a respected City businesswoman named Ellen Cotes, the 1665 Bills of Mortality are a rare and unique record of life and death during the Great Plague of London. With title pages edged in black and decorated with striking memento mori of skulls and skeletons the Bills record how at least seventy percent of those who died that year perished of the dreaded bubonic plague. By insisting on recording and publishing all reported deaths – alongside enforcing household quarantines and ensuring food supplies – Lord Mayor of the City of London, Sir John Lawrence, gained praise for including the public in managing the evolving health crisis.

With the re-emergence of bubonic plague in the port cities of Hamburg and Amsterdam, in May 1664 quarantines had sensibly, if unpopularly, been imposed by the English government on all merchant-sailors entering the Thames estuary, as well as on the goods they brought with them. And at about the same, throughout that year – from the New England Colonies of British America to the ancient Kingdom of Korea – a fiery comet was observed in the night skies. By December 1664 it was widely witnessed in England by, amongst many others, naval-administrator Samuel Pepys, and Cambridge undergraduate Isaac Newton. Even the “Merry Monarch” himself, King Charles II, and his Queen were said to have sat up late to behold it. The coffeehouses of London were abuzz – and some even claimed the comet had made an ominous roaring sound. Warily, wrote Pepys, “God avert its ill bodings (if it have any)”.

By the spring of 1665, the plague was spreading fast and household quarantines fully came into force just as the nation manoeuvred to war once again with the Netherlands. And as the Royal Society began publishing their first scientific journal, Philosophical Transactions, the Puritan preacher John Bunyan began writing The End of the World. Streets were emptied and shops shut-up. By the summer, those who could had fled to the relative safety of the countryside. Although Pepys remained quite happily – and profitably – in town, he sent his wife away carrying the family gold. With Cambridge University feeling it prudent to close its doors, the young Isaac Newton was sent into (what turned out to be a very learned) lockdown at home in Lincolnshire. Naturally, the King – described by contemporary libertine John Wilmot as “pretty, witty” and “foolish” – escaped London for Wiltshire and Devon; his Parliament choosing to sit in Oxford that autumn. And thanks to measures imposed by the Edinburgh government, although the plague reached as far north as the village of Eyam in Derbyshire – and with tragic consequences – it never reached Scotland.

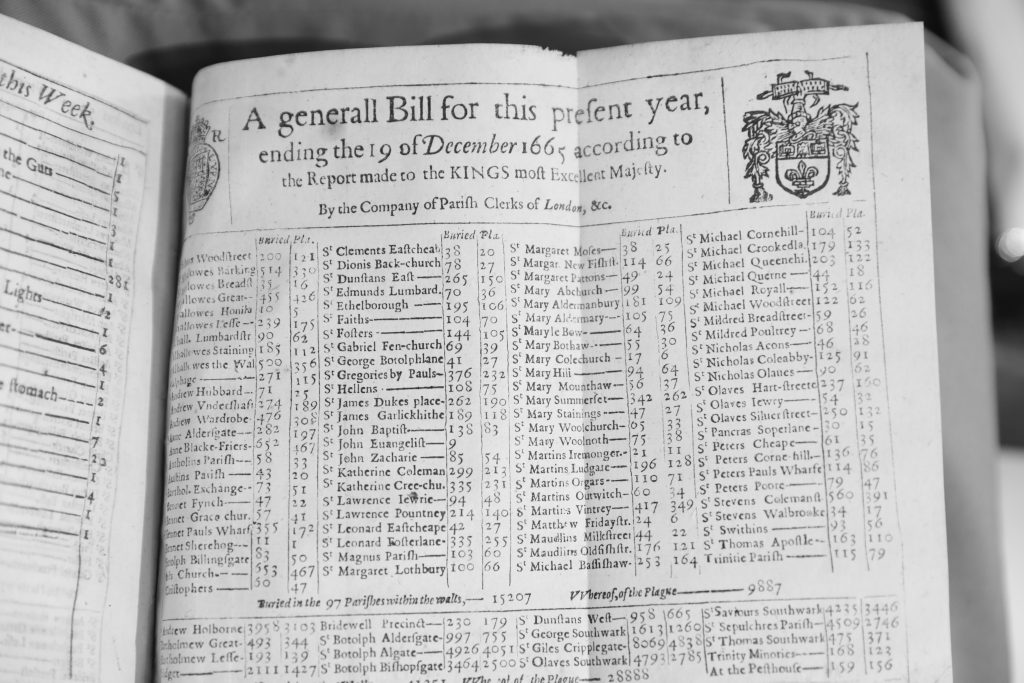

Without formalised medical training and unable to afford a doctor, it was ordinary women who nursed the dying and who gained an experienced understanding of the disease. For this precisely this reason, the City of London employed pairs of experienced local women from each parish as amateur coroners, or Searchers. If Anglican, when a person died their passing would be reported to the local parish church. Bells would ring, calling the Searchers to immediately attend the body and, through close inspection, determine the cause of death. Over an eighteen-month period an estimated 100,000 people died of the bubonic plague – almost a quarter of London’s then population. But whatever the Searchers concluded the cause of death to be, they would report their verdict to the local Constable. He would the pass it to the Parish Clerk who would, in his turn, pass it to the Clerk of the Company of Parish-Clerks, whose job it was to collate all the information received.

During the crisis of 1665 the Company clerk needed the numbers of dead and the causes of each death by the end of each Tuesday; setting and printing – by Ellen Cotes and her firm – would always occur on Wednesdays. Cotes’ press was so valuable it was triple-locked; key being held by three trusted souls. Such was the importance – and power – of public health information that any disruption of its established flow carried a punishment that could include flogging. Delivered to his door on Thursday mornings, the first recipient of the Bills was Sir John. Only then, on Thursday afternoon, were copies released to street vendors to sell to the buying public.

As such, according to historian Will Slauter, the Bills “depended upon the collective efforts of hundreds of individuals acting at the local parish level” and were “collaborative texts that fed back into the collective behaviour of the community”. Local knowledge combined with available data enabled policy-makers and the public alike to better understand the crisis and protect one another as much as was then possible.