The desire to replicate nature in print has created some of the most desirable and collectable publications in the book world, as well as incredible developments in printing techniques. These have consequently often been adopted by artists interested less in botanical science and more in aesthetics. From the woodcuts used in the monumental early herbals, to the use of collotypes to reproduce the essence of flowers in the artwork of Gustav Klimt, our blog today takes us through some key moments in the history of botanical illustration.

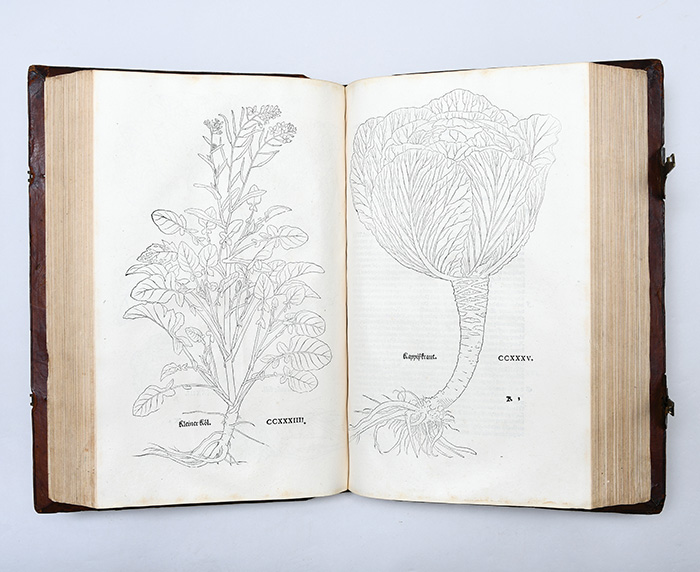

Leonhart Fuchs De historia stirpium, printed in 1542, was “one of the landmarks of pre-Linnaean herbal-botanical literature”, richly illustrated with woodcuts and containing the first printed glossary of botanical terms. It encompasses over 400 German species and 100 foreign species of plants, most of which were drawn from samples in Fuchs’s personal garden. The woodcuts of the plants are to scale and include their root systems and, often, sample-specific details such as leaves damaged by insects. They established a standard of plant illustration still followed to this day. For the illustrations, Fuchs employed three artists: Albrecht Meyer, who drew the plants from life, Heinrich Füllmaurer, who transferred the images to woodblocks, and Veit Rudolph Speckle, who undertook the woodcutting. Portraits of these men all appear in the book itself, making it “one of the earliest examples of such a tribute paid to artists in a printed book” (PMM).

The first German edition of 1543 was extensively revised and enlarged with six additional illustrations and a new index. With these changes and its stronger medicinal focus, the function of woodcuts was further sharpened with their accuracy to nature paramount for their scientific use.

What is a woodcut?

Woodcuts are a form of relief printing. They are difficult to get right and take considerable skill to produce. The image is carved into the surface of a block of wood, that crucially has been cut along the grain. The nature of wood means the grain can have a significant effect on the final product if not carved with care.

The areas to show white in the finished image are cut away with a gouge, knife, or chisel, leaving the characters or image to show at the original surface level. The surface is covered with ink using a roller and the paper is then pressed over the inked surface to produce the image.

As woodcuts and movable type are both relief-printed this method was the main medium for book illustrations until the late 16th century.

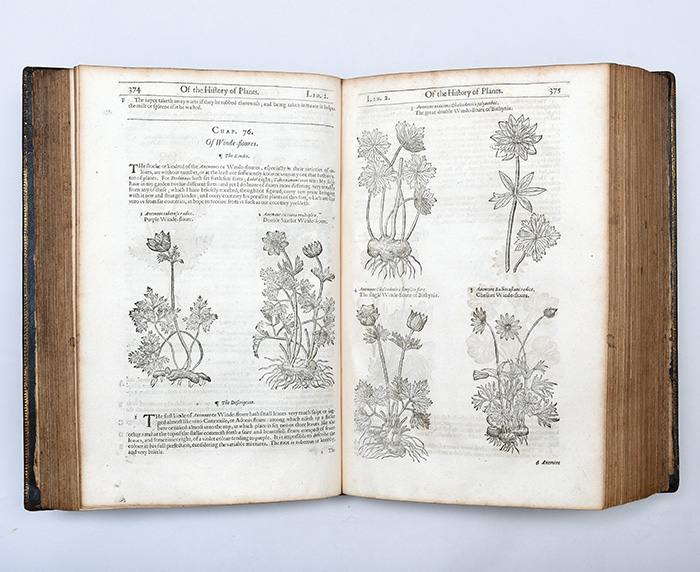

John Gerard’s The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes was published in 1597 and became most famous herbal in the English language. For that richly illustrated edition the publisher used borrowed woodcuts from the German physician Tabernaemontanus’s Neuw Kreuterbuch, published in 1588. The production of the woodcuts was funded by Count Palatine Frederick III and the publisher Nikolaus Bassæus, and the first volume took 36 years to produce. They were later acquired by the printer John Norton and thence used to illustrate the plants described by Gerard, demonstrating the practical nature of book production at the time.

In 1633 a much revised and enlarged edition of Gerard’s Herball was issued by the keen botanist Thomas Johnson, his corrections to Gerard’s original text diligently marked up. Johnson’s edition was also expanded with new illustrations. These were taken from Rembert Dodoens’s herbal Stirpium historiae pemptades sex, originally published by the famous Antwerp printer Christopher Plantin in 1583, and they were praised for the finer level of detail they provided.

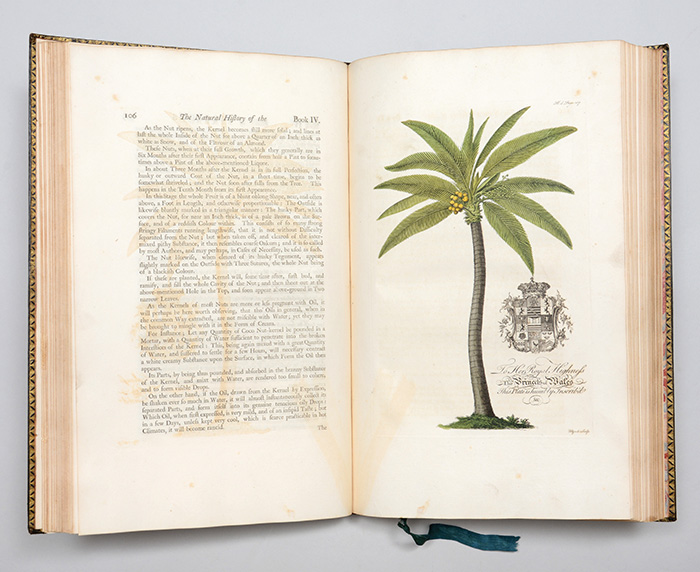

During the 1700s the flourishing genre of travel accounts meant an increase in botanical plate books depicting plants from across the globe. Griffith Hughes’s The Natural History of Barbados was published in 1750 with a large paper issue that featured 25 of its 30 engraved plates hand-coloured. 12 of the plates featured were after renowned botanical artist Georg Dionysius Ehret, one of the greatest botanical painters of the 18th century and the most dominant influence in the field. The botanical plates in Hughes’s work are listed as engraved by James Mynde, George Bickham (who also drew the artwork), and, some scholars claim, Ehret himself. Unfortunately, his skill as a painter was not matched by that as an engraver, being described as “usually competent – but uninspired” (Blunt, p.149).

What does it mean for an engraving to be “after” someone?

Engraving (intaglio printing or gravure) was invented in Germany in the 1430s and was developed as an original art form in the 15th and 16th centuries by artists such as Albrecht Dürer, Lucas van Leyden, and Andrea Mantegna. The image is incised into a plate, initially copper and later steel, and the cut line then holds the ink: the deeper the cut the darker the impression. This is the reverse of a relief print like a woodcut. Incisions can be made by a wide variety of methods, including using a burin, needles, or acids. A plethora of printing techniques were consequently developed in this medium and they allowed a greater accuracy in reproducing drawn and painted works.

In the 18th century the practice of engravers reproducing the work of artists in a more accessible form became highly popular. Although a remarkably close copy of the original was possible, at this point it was impossible for a reproductive print to be a perfect replica of a painting. Reproductive prints therefore often distorted the intention of the painter, whether unintentionally or not: some engravers gaining a reputation for softening images, idealizing them, or making them more picturesque. Indeed, some artists such as Joshua Reynolds were particularly careful to allow only those engravers in which they had certain confidence the privilege of reproducing their work, recognizing the interpretive nature of the job.

Engravers were often named alongside the original artist on the plates, their skill in copying the details of the original artwork recognized, and their plates listed as “after” the artist.

Hand-colouring of botanical plates existed from the earliest herbals: the publisher of Fuchs for example issuing copies in a coloured state based on Fuchs’s coloured drawings of living specimens. Hand-colouring of copper-engraved plates theoretically allowed a level of accuracy that the black and white printing could not, and it was standard in botanical works into the 19th century.

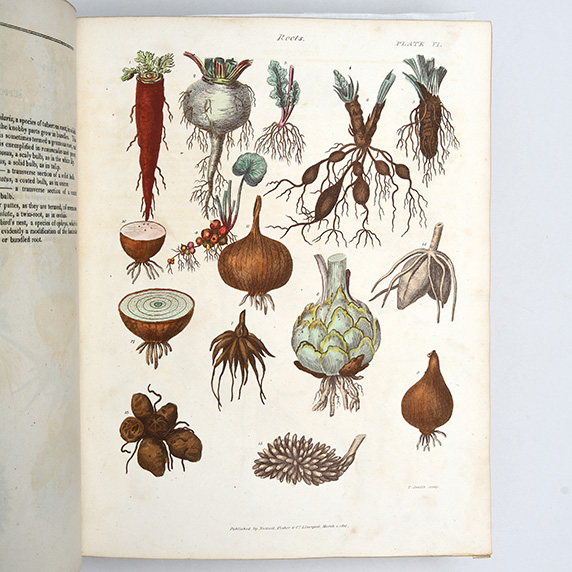

Thomas Green’s The Universal Herbal, for example, first issued in parts from 1816 to 1820, was an encyclopaedic work that claimed to list all the known plants in the world. The revised edition of 1823 featured 106 hand-coloured engraved plates. From the 1830s that form of colouring was replaced by a wave of new methods, including aquatints, mezzotints, and stipple engravings, often printed in colour. This period is often referred to as “the finest hour of colour printing” (Sitwell, p. 1). By the end of the 19th century the chromolithograph, the colour printed directly on the stone with the etched design, had become the predominant method of botanical printing for books, with some regretting the loss of detail this more efficient and cheaper method entailed.

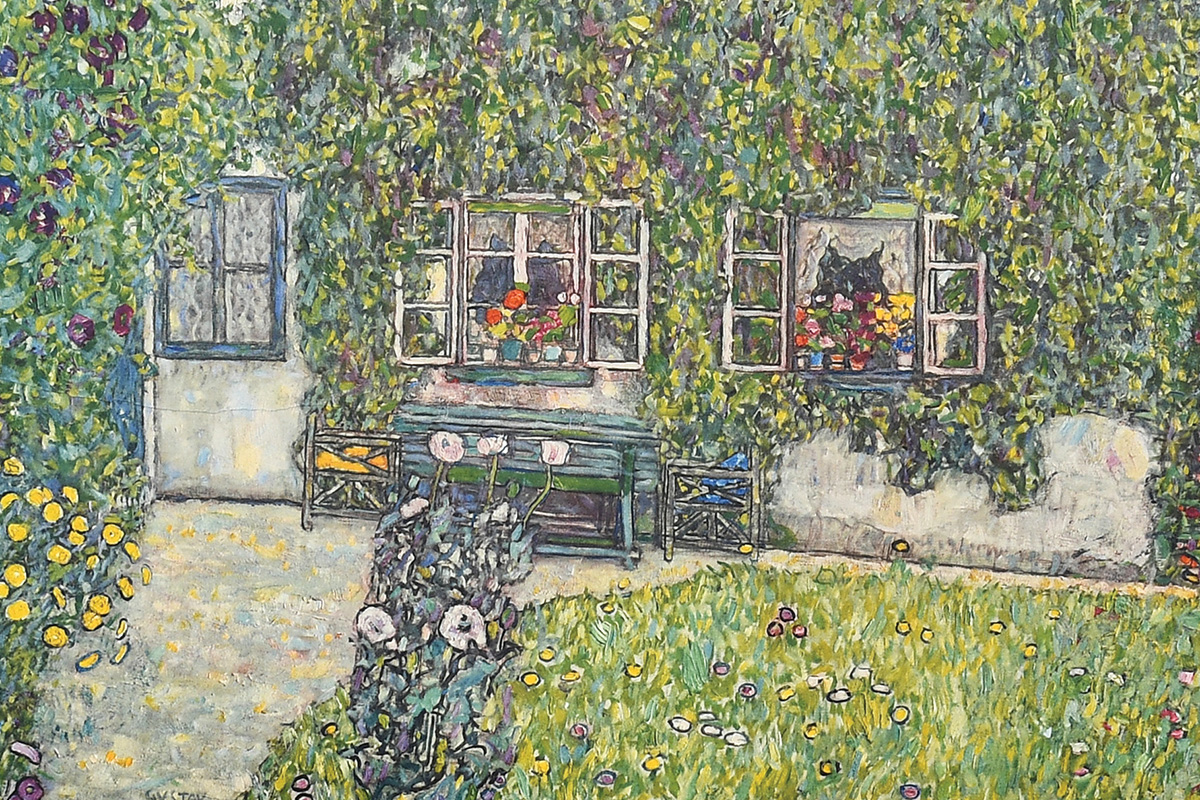

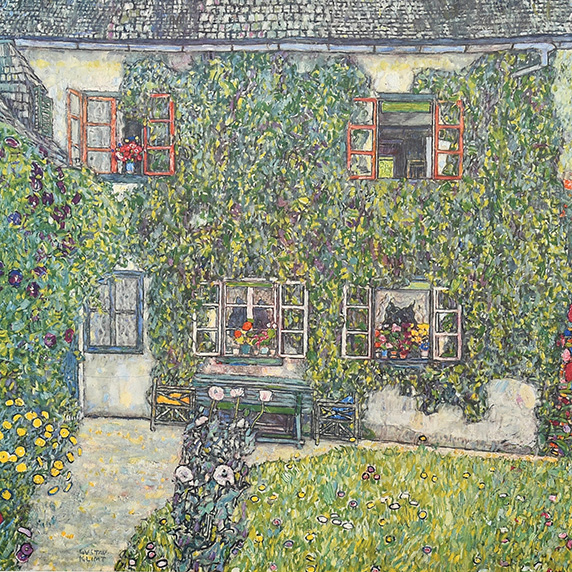

New methods of printing, including photographically based reproductive printmaking, appealed both to botanists and artists alike. While the botanical illustration discussed thus far aimed for near perfect accuracy with a scientific purpose, the corresponding world of flower painting that developed alongside it was all about the aesthetic. Although remembered most for his portraiture, botanicals and landscape painting became an increasingly important outlet for Gustav Klimt from the 1890s onwards, and stylised floral motifs appear throughout his work.

His portfolio Eine Nachlese, was printed in 1931 by the art historian Max Eisler using the collotype printing method. This fragile technique was often employed by artists for its ability to reproduce the subtle delicacy of drawings, as well as the tonal gradations of the original work. The fine chine colle paper Eisler used for the portfolio allowed even greater colour saturation, and the resulting prints are now some of Klimt’s most well-regarded.

What is a collotype?

Collotype is a form of photographic printing invented by Alphonse Poitevin in 1855. It was the first form of photolithography. The complicated, lengthy process involves gelatin colloids mixed with dichromates (salts of certain acids). A photographic negative is projected onto a printing plate coated with light-sensitive gelatin that hardens and becomes receptive to the application of ink. Paper is laid on top and the image is printed. It became an increasingly popular form of fine art printing in the 19th century. Fragile hand-printed collotype plates cannot be reused, so the run must be completed on the first go and in only a limited number, adding to its appeal, if not cost-effectiveness. Endeavours to make this labour-intensive and time-consuming process economically viable for large print runs failed, and consequently it fell out of popularity by the latter half of the 20th century.

Written by Rare Book Specialist, Suzanna Beaupré

Bibliography

- Wilfrid Blunt, The Art of Botanical Illustration, Collins, 1950.

- Sacheverell Sitwell (ed.), Great Flower Books 1700-1900, H. F. & G. Witherby Ltd, 1990.