Today’s post is a collaborative effort with my colleague Adam Douglas.

The philosophy of book dealing has changed radically since the days when dealers stripped every trace of prior ownership from books before reselling them, going so far as to wash medieval marginalia from the pages of manuscripts. Today, both dealers and collectors have a firmer grounding in the history of books and understand that vestiges of ownership not only give a book character, but can be valuable historical and cultural artefacts. Our practice at Peter Harrington is to preserve as much as possible about a book, including bookplates, ownership inscriptions and even the ephemeral items that we find nestled in the pages. But what do you do when those traces of the past are fraudulent?

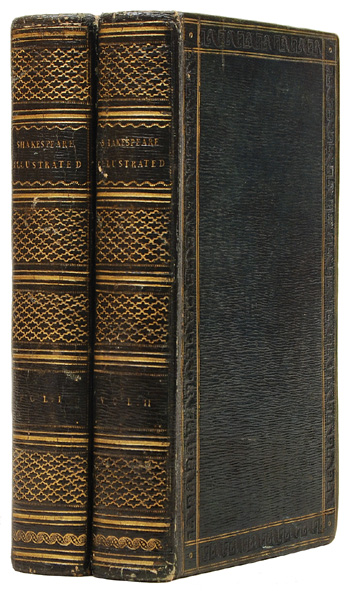

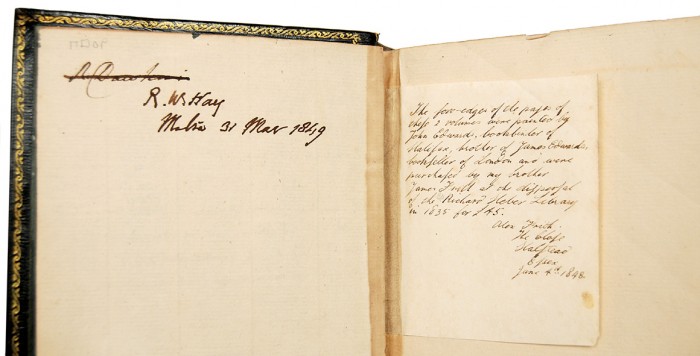

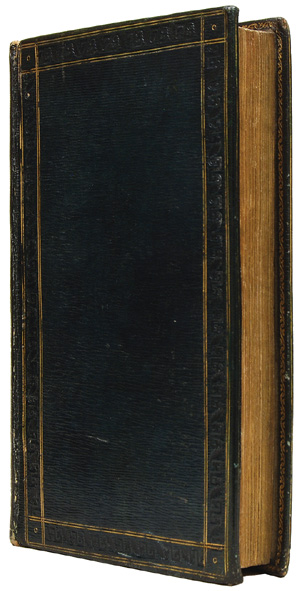

Last year a book runner dropped by the shop with a two-volume set of Shakespeare Illustrated, published in London in 1793 and bound in attractive Regency-era blue morocco.

The most interesting aspects of the set were its fore-edge paintings, miniature artworks painted onto the leading edge of the leaves that can only be seen when the pages are fanned. The runner claimed that these particular paintings were executed and signed by John Edwards of the Edwards of Halifax family, innovative booksellers and binders in London during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. John Edwards created some of the firm’s famous painted vellum bindings, and his fore-edge paintings are now highly sought-after. “Paintings signed by him are rare,” the runner reminded us.

The fore-edge of one volume as it normally appears. All that can be seen is the gold leaf covering the painting.

We bought the books but, as sometimes happens in large bookshops, they were set aside on the reserve shelves for over a year. When we looked at them again we were intrigued, but not in the way that we’d expected.

Our first indication that something was amiss was that the artist, who signed the paintings as “J. E.”, had also dated them to 1799. One of the reasons for the scarcity of fore-edge paintings signed by John Edwards is that he mysteriously disappeared during a business trip to Paris in 1793. His family came to the conclusion that he had run afoul of the revolutionary mob and been guillotined, but whatever the case, he was certainly not executing bindings in 1799.

Next we come to the book itself. Although done in Regency style, it doesn’t have any of the characteristics of a true Edwards of Halifax binding. It is not Etruscan calf or painted vellum, and the border decoration is not the Edwardses’ splendidly named “metope-and-pentaglyph” roll. The image below and to the left is a detail of the border decoration on our volumes, composed of alternating Greek key and leaf designs. To the right is a lovely metope-and-pentaglyph roll on a true Edwards of Halifax binding (many thanks to Phillip J. Pirages Fine Books for providing the photo). The metopes are the concentric circles and the pentaglyphs are the lozenges grouped in five.

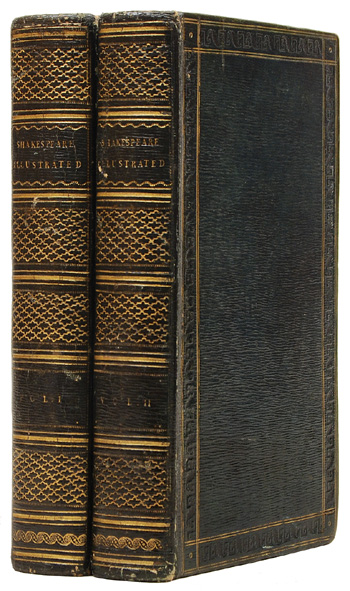

On the front pastedown we found, reassuringly, the bookplate of the Earl of Rosebery (1847–1929), a prime minister and noted book collector unlikely to be fooled by a false fore-edge painting. Unfortunately, the plate only appears in the first volume, whereas Rosebery would normally have placed one in each volume. This example is also worn and scratched, as if it was removed from another book and pasted here to add authenticity.

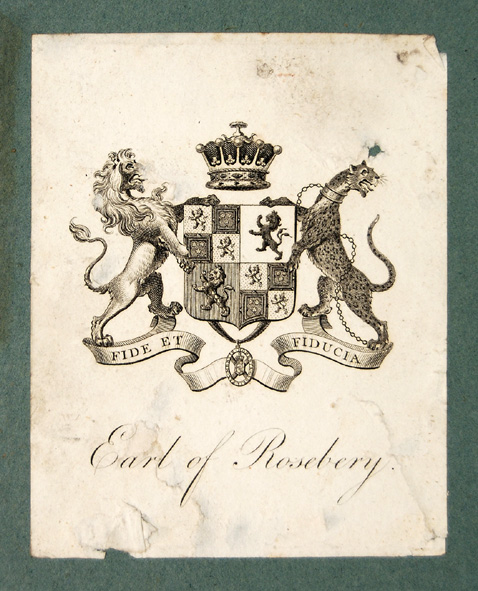

By far the most spurious evidence is found at the front of each volume. Each is signed and dated 31 March 1849 by R. W. Hay. Tipped in opposite is a hand-written note, presumably by the person who sold Hay the books. “The fore-edges of the pages of these 2 volumes were painted by John Edwards, bookbinder of Halifax, brother of James Edwards, bookseller of London and were purchased by my brother James Frith at the dispersal of the Richard Heber Library in 1835 for £45. Alex Frith, The Close, Halstead, Essex, June 4th 1848.”

That seems clear enough at first glance. Richard Heber is probably the most famous book collector in English history: the term “bibliomaniac” was coined for him. He owned some 15,000 printed books, and his sales catalogues run to sixteen volumes. But £45 sounds like a lot of money in 1835, and we know from other reference sources that his copy of the second folio of Shakespeare made £10.5s. So according to the note, Alex Frith’s brother allegedly paid five times as much for these pleasant but ephemeral volumes as the second edition of Shakespeare’s plays made at the same sale. What Frith seems to have provided for the hapless Mr. Hay is the Victorian equivalent of an eBay certificate of authenticity.

So everything about the book speaks of a long history of fraudulent claims. Is it entirely worthless? We don’t think so. Described honestly, as an attractive book in an anonymous contemporary binding, we feel we can price it competitively. That leaves the question – should we remove the Rosebery bookplate and Alex Frith’s mendacious little note? To allow them to remain is to risk that future buyers will be duped, but removing them destroys the record of the deceit, which is interesting and even historically significant in its own way. What do you think? Let us know in the comments.