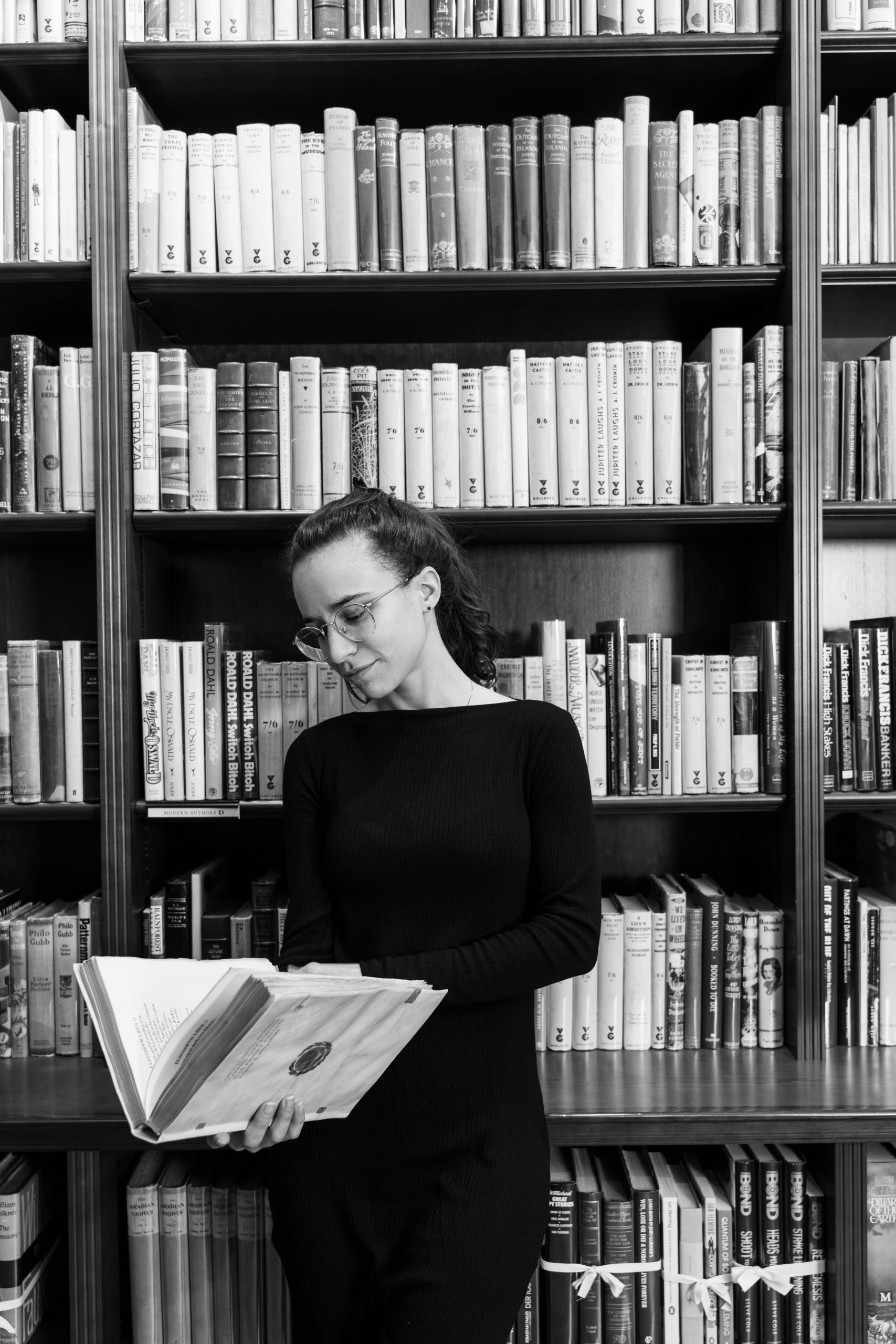

The latest in our The Booksellers series, our cataloguer Alessia Colombo shares her journey into the rare book world, her area of interest, and some of her favourite experiences working at Peter Harrington.

How did you come to be a cataloguer at Peter Harrington?

When people ask me how I found my way into the rare book trade, I always jokingly say “by accident”. I like to think that the books found me, rather than the other way around. I have always had a passion for literature, and especially for the history of writing – I began to study Latin at 12 because I was excited at the idea of learning how to decipher ancient texts. After finishing my BA degree in Classics in Milan, I moved to London for my Master’s degree, which was in archaeology.

My dissertation was on ancient Roman writing materials, and, if anyone is curious, I have just recently published an article in the academic journal Britannia on the subject. But back to the books! After graduating, I knew that digging wasn’t really my thing, so I started to look for a job where I could use my knowledge of literature, ancient languages, or my new skills in working with artefacts. I came across a job opportunity as a freelance rare book cataloguer at Sokol Books on my university careers portal and I thought I’d give it a try. I quickly realised that cataloguing brought all my passions together – after about a year, I applied for a position at Peter Harrington, and here I am.

What do you enjoy the most about working with a rare book dealer?

I would probably say the discoveries. I have the unique privilege to examine, spend time, and learn from extraordinary historical items – every single day. Some of the books we acquire are so rare that you are lucky to come across one single copy in your lifetime; some others don’t look like much at first, but when you start researching them, they turn out to be incredibly interesting. This means that every day there is a chance that in my pile of books there might be a treasure hiding, and discovering it is my favourite part. Just recently, I took from our cataloguing shelves what – at first – looked like just another early political treatise: Dodici libri del governo di stato, by Ciro Spontone.

After looking into it, it turned out to be one of the most irreverent, anti-Machiavellian works ever written, full of direct personal insults towards Machiavelli, who is labelled a “viper” and compared to a demon.The author was one of the earliest opponents of Machiavelli’s theories, and this book is a fantastic forgotten piece of history. I love bringing these stories to light. Also, because the range of materials we deal with is really vast and spans all time periods, it never gets boring. One day I am looking at the first Italian book on chess; the next day at a copy of Salvador Dali’s only novel, signed by him, and on another at the first printed example of a sign language or the first edition of Shrek. There is never a dull moment.

How do you feel that the industry contributes to the preservation of culture and history?

The antiquarian trade is often portrayed as a closed off, elite space that is only open to a few lucky collectors – I had a similar view before starting to work as a cataloguer. Although rare book collecting may appear to be out of reach for some people, we are constantly working to making our stock easily accessible for the public to see and engage with to help encourage new collectors to engage with the trade.

As rare book dealers, we have the resources and time to look for, find, and acquire the most unique items and manuscripts, and as I mentioned before, this often leads to the discovery of amazing material which would otherwise hardly come to light. I strongly believe in the potential of our platforms as powerful means to spread knowledge and promote research: every week, we create new videos, newsletters, and blog posts about our most recent discoveries and outstanding items.

Our website and physical catalogues contain accurate descriptions and images of thousands of books that can be accessed by everyone; some of this information cannot even be found in institutional databases. We organise periodical exhibitions in our gallery, participate at book fairs every year which are free for the public, and our specialists collaborate in seminars with external institutions. Recently, in our Shakespeare exhibition, we brought together and displayed all four folios and the first collected edition of the poems, the first time it’s been done so in a generation.

At Peter Harrington, we are very aware of the uniqueness, quality of preservation, and historical value of the items we acquire. Some of these items find their ways into institutional holdings. We are always happy to arrange in-person viewings with researchers interested in studying any of our items.

You often focus on early printed texts in Latin, Greek, and continental languages. How do you go about researching and finding the books for Peter Harrington?

I always try and offer an interesting, fresh angle in my descriptions, to bring these books back to life. Early books, especially when they are written in ancient or foreign languages, might seem very distant from us – in reality, they are a mine of curious ideas, theories, and views of the world that can still inspire or entertain us today. So, when I am researching a Renaissance text, or an early edition of a classic, this is what I am looking for.

But then, I always say that every copy of a book tells two stories: the one it contains, and its own. When I have established why the text is important, then I also look at why this specific copy is interesting. This usually means researching its provenance. I am always looking for the small detail on the binding that might indicate where it was made, or the small inscription that no one has noticed (or cared to research) before.

Sometimes, if you are lucky, inscriptions will reveal details of the person who previously owned the book, what their interests were, their background of studies, or their profession. Understanding the reasons why someone in the Renaissance decided to buy a book is very important when assessing its historical impact, and this ultimately influences why someone might decide to buy it today.

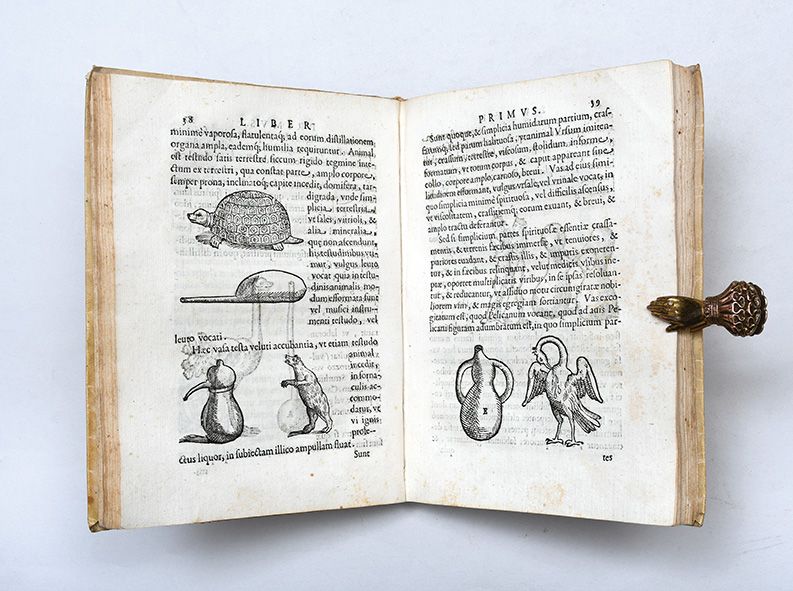

DELLA PORTA, Giovanni Battista. De distillatione lib. IX. 1608.

You have a particular interest in alchemical books as an early form of chemistry. Can you tell us more about this?

In the early modern period, the line between alchemy and chemistry wasn’t as neat as we draw it today – something similar might be said of astronomy and astrology. I am fascinated by the history of the development of modern sciences, and love looking at the overlaps between disciplines in the Renaissance. Some of the practitioners who were called “alchemists”, or even “magicians”, were in all effects carrying out scientific experiments which lead to defining laboratory techniques that are still in use today.

Alchemists such as Paracelsus were the ones who introduced the idea of employing chemicals in medicine. One of my favourite examples from our stock is Della Porta’s De distillatione, a treatise on distillation explaining how to extract the essence from natural objects. Among the various chemical and alchemical procedures listed in the book, we find a beautiful woodcut which is one of the earliest representations of solar distillation equipment.

Peter Harrington is best-known for its rare book collections, and many of those books include things such as inscriptions and marginalia. What are some of the most interesting details you have found in the books that you work with?

There are so many examples. My favourite are the inscriptions which reveal something about the reader’s personal character and opinions. We have a copy of Scot’s The discoverie of witchcraft (1584) in which an early annotator, disagreeing with some of the contents, called the author of those passages a “magisterculus” (“a small mind with oversized pretensions”), and in another instance commented: “I despise the blindness of the author and his lack of intelligence”. Another amazing survival is an early manuscript astrological chart, on a piece of paper inserted in our copy of Magini’s Ephemerides (1608), an early almanac. Following the indications provided in the book, a near-contemporary owner produced a diagram, likely a birth chart, tracing the position of the planets at 9:30 (civic time) on 10 May 1652.

Inside the almanac, in the margins of the astronomical tables for the year 1612, this early owner also recorded – or perhaps predicted – the meteorological conditions of a few days: for example, “sereno” (clear), “pioggia” (rain), “nibia” (fog), “freddo” (cold). More often, students and scholars would simply underline important passages and write summaries in the margins. So, I wasn’t too surprised to find this kind of annotation when I flipped through the pages of our copy of Setzer’s 1533 edition of Isocrates. However, when I looked at the back, I was excited to discover a four-page manuscript list of variant readings and corrections to the Greek text.

What has been one of your standout experiences working with Peter Harrington?

My favourite discovery. I was looking at our copy of the first edition of Erasmus’s Complaint of Peace, published in 1517 in Basel, and I saw a small Latin ownership inscription: “Sum Petri Scudi Glareani” (“I belong to Peter Tschudi of Glarus”). I was very excited to find that this was not only an important Swiss humanist and a friend of Zwingli, but also a figure active in Reformation circles and by extension known to Erasmus himself. The book is in a beautiful contemporary binding, which can be attributed to a Parisian workshop.

The details of Tschudi’s life are well recorded, and we know that in 1517, the year of publication of Erasmus’s book, he moved from Basel to Paris. This means that he very likely bought the book in a shop in Basel, brought it with him to Paris, and then had it bound according to the contemporary French fashion. It is extremely rewarding to find out that a book is even more valuable than everyone originally thought it was.