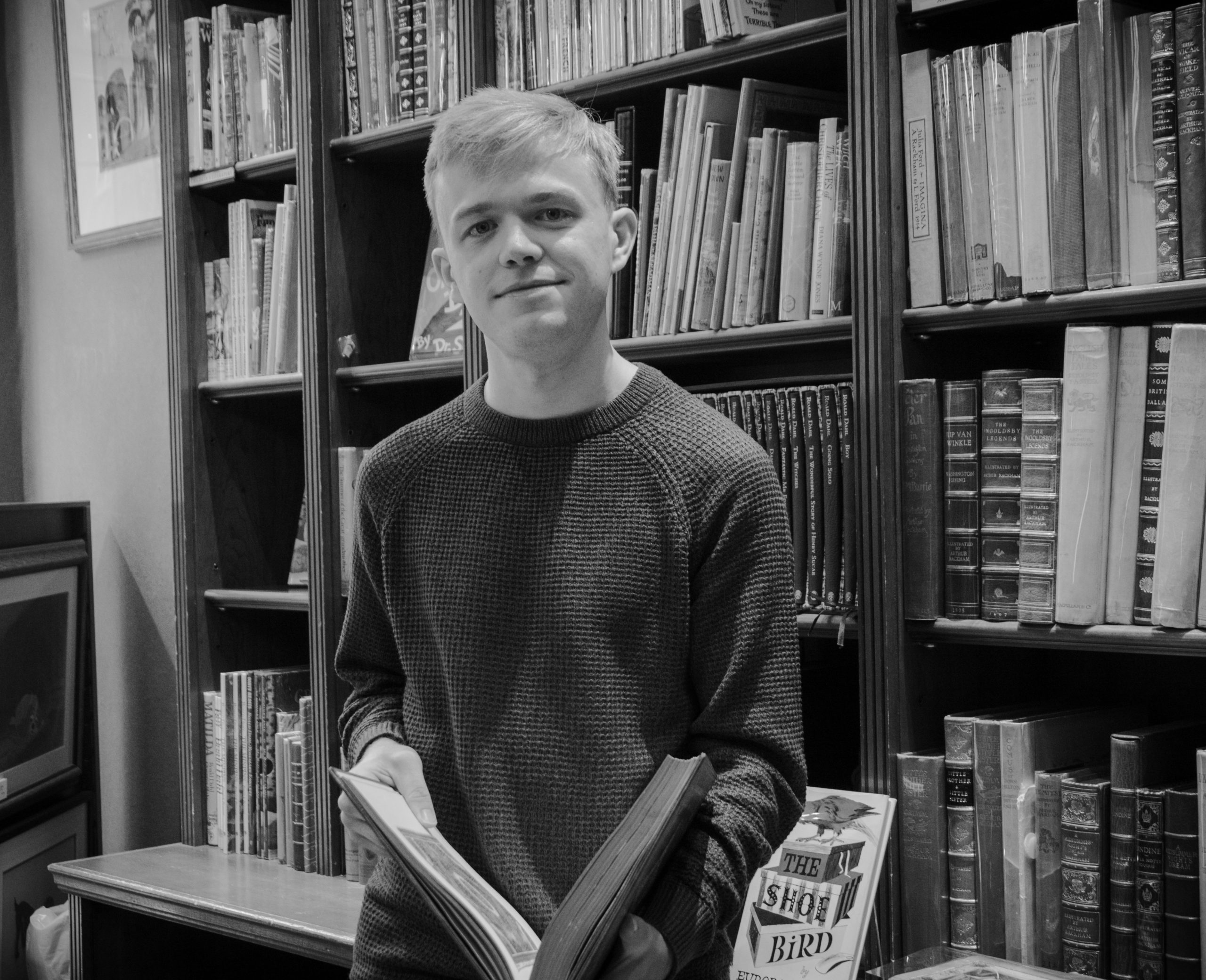

The latest in our The Booksellers series, our cataloguer Mark Pickett discusses his role at Peter Harrington Rare Books, his areas of interest with the rare book trade and some of the more interesting items he has come across in his work.

What are your main responsibilities as a bookseller and cataloguer at Peter Harrington Rare Books?

Broadly speaking, a book goes on three journeys through Peter Harrington: acquisition, cataloguing, and selling. I mainly do the cataloguing, which involves confirming an item’s authenticity, researching its history, and writing the descriptions that accompany all our items. Whether you are browsing our website, one of our branches, a newsletter or even a book fair, it is vital that your bookseller provides reports on an item’s condition and what makes it worth collecting. That’s where cataloguers come in. An item shines when its strongest selling points are presented in a clear and concise manner, and I store away additional information for conversations with customers in my other role as a bookseller. When answering the phone or greeting visitors to our shop in 100 Fulham Road, my goal is to make clients as excited to discover our stock as I felt while cataloguing them.

What do you enjoy best about working for a rare book dealer?

The tangible atmosphere of passion and willingness to share knowledge is a great bonus. As a cataloguer, I would say the variety of material I work with. No two customers share the same interests, and we aim to serve them all by providing beautiful and foundational items in all kinds of areas. Here is what that looks like: last week, I finished cataloguing an inscribed copy of The Tanks (1959) by great military theorist Captain Liddell Hart, set it aside with an animation studio’s box containing films and records of famous American children’s books, and turned to a curious miscellany of magic and captivity aptly titled The Mental Novelist (1783). Each day brings new piles of wonderfully diverse material offering their own unique cataloguing challenges that are always a pleasure to solve. Sometimes, that entails familiarising myself with new subjects. I can’t claim an academic background in philosophy, but I can explain how Bertrand Russell’s History of Western Philosophy (1946) was first published in the UK with dust jackets printed on the reverse of surplus wartime maps. It’s an imposing visual reminder that commercial and other worldly forces are inseparable from the intellectual exchange of ideas. This is the framework I use to understand all the books I catalogue, regardless of the subject.

You tend to come across quite interesting items in the course of your work. What would you say is the most interesting item you have handled?

After escorting material from our landmark Shakespeare sale, a colleague dubbed me the “First Folio Bodyguard”, but I’m not sure that item counts. One of my personal favourites is an early scientific travelogue Nabokov wrote in the scarce 64th volume of The Entomologist. It stands at the heart of Nabokov’s complimentary and competing passions for literature and lepidoptera (moths and butterflies). In this essay, the editors of Nabokov’s Butterflies (2000) tell us, the writer “had thrown off any constraints at expressing his feelings and perceptions in an entomological article, and portions of it read no differently from his fiction” (p. 40). Published in 1931, the volume shows a novelist and taxonomist still growing in strength. It comes before his first novel originally written in English, The Real Life of Sebastian Knight (1941); before his first discovery of a new species of butterfly in 1938, the Lysandra cormion; and decades before Lolita (1955). The essay reminds us that there was more breadth to Nabokov’s life and talents than “only” being one of the greatest novelists of the 20th century.

Paradoxically, what draws me to this book is its apparent unassuming nature. There is nothing to indicate this publication deserves a place in a collector’s library of modern first editions, unless, of course, you somehow already knew that buried between pp. 255-7 and 268-81 is that crucial Nabokov essay. This also helps to explain its rarity. While cataloguing it, I traced just two copies in the world held in public institutions. No doubt many more copies have been passed over, disregarded for being, well, the 64th volume of The Entomologist. It was a great privilege to rediscover another copy and offer it for sale in its full context, telling of that young Russian who, in words and wings, revelled in aesthetics.

Recently you’ve been cataloguing novels and stories associated with popular films. Can you tell us about those?

To me, these items are fantastic demonstrations of why we collect books: going back to the source material, the physical objects that underpinned literary masterpieces and cultural phenomena. We are all familiar with the film sets of Peter Jackson, but what does an original set of The Lord of the Rings (1954-55) books look like? How did James Bond make his dramatic entrance to the world? Those initial few thousand readers who learned of a wizard boy named Harry Potter before anybody else – what kind of object(s) were they holding, and can I hold it too? You can at Peter Harrington, and if that sounds like time travel, it’s because it is.

If there were any rare book that you could have for yourself from our stock, what would it be?

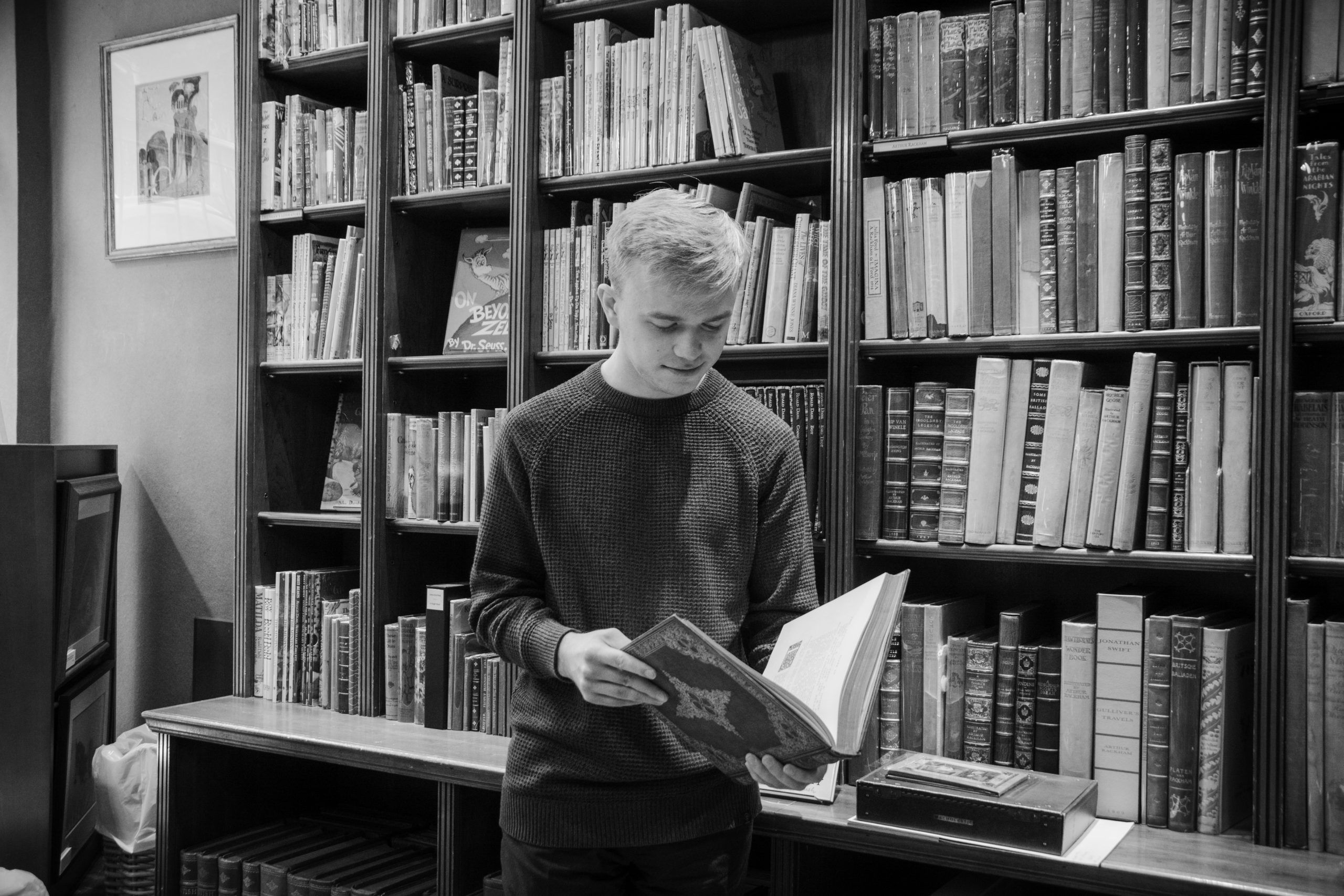

I’ll aim high. The 1532 edition of Chaucer’s Works, the first collected volume of any English author, ours being the most complete copy to enter the market in three quarters of a century. Its astounding beauty aside, this is the book that first argued our vernacular language should be collected and its canon curated in comprehensive singular volumes. It speaks out, telling us that English literature is worthy literature, on par with ancient classics and as deserving of our attention (for context, it was not until around 1910 that the first degree in English literature was offered at British universities). The book is a fundamental starting point that provided the model for the supreme achievements of English collected editions and of fine printing, the Shakespeare First Folio and the Kelmscott Chaucer. It is so much more besides.

My Sixth Form headteacher taught us that, to really enter Chaucer’s world, we needed to recite his poems in their original pronunciation. If one recited from this copy, in the domestic comfort of their own home, they might well feel upon their shoulders the weight of not only the medieval period, but of 500 years of literary tradition in English vernacular, from Chaucer to Joyce, and beyond.

What do you think people would find most surprising about the rare books trade?

It’s no surprise the trade involves detective work, but our methodology is perhaps less well known. An obvious form of research is provenance, and among my favourite discoveries in this area was identifying Elizabeth Rice (1800-1884), the former owner of a collection of correspondence between three women of letters, as the niece of Jane Austen. Other clues are more arcane, particularly when it comes to leather book bindings. A colleague recently shared that russia leather is identified by its spicy smell, and now I can’t unsmell it. Sheep is cheap, often stripping away in long, thin pieces, while pigskin, when you inspect it very closely, has a grain that comes in threes. By interrogating a book’s external appearance and aging process, we find answers to such questions as who bound it and when, how and for whom, and (crucially) has it been altered since.

Case in point: I once catalogued a book that just felt wrong. The red morocco binding appeared contemporary to the work of 1825, but it seemed too shiny, too sticky, and somehow out of place. Looking it over, one of our senior specialists declared the binding had been removed from its original book and placed onto the edition it currently clothed. In a word (there’s usually a word), it was a remboîtage. It takes handling thousands of books to build up the knowledge base of a diligent rare bookseller, and very few professions provide the sample size required for our brand of bibliophilic sleuthing.