“Dear Boys and Girls”: Enid Blyton’s personal brand

Whether its a debate on whether her novels ought to be updated for the 21st century or a series of parodies for the post-Brexit world, Enid Blyton remains a staple of the cultural canon.

Despite dated language and objectionable attitudes to gender, class and race which occasionally mar the fun for a modern reader, her books still largely inform the conception of what British children’s fiction ought to be: plots full of mystery, intrigue and adventure, emphasis on a moral code of courage and friendship and, of course, sumptuous descriptions of tuck shop snacks, picnics and midnight feasts.

The enduring popularity of such themes with young readers can be read, for example, in J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter, which offers an update on the boarding school novel, with a cast of young friends out to foil the plots of wicked adults (albeit with higher stakes and a more complex moral message).

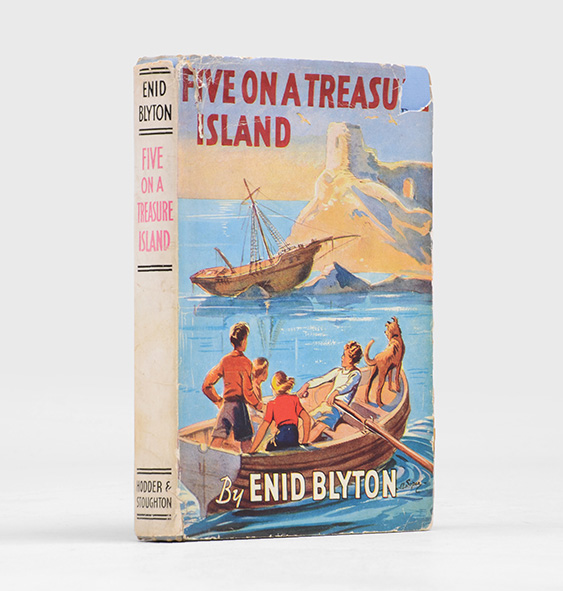

Five on a Treasure Island, 1942. First edition of the first book in the Famous Five series.

It was, perhaps, Blyton too who provided the pattern for the modern day superstar children’s author that Rowling and others such as Jacqueline Wilson and Philip Pullman currently embody – not only the creators of a much-beloved world on the page but also active public figures, engaging with a community of young fans.

In a time before social media, and when publishers hadn’t yet developed the sophisticated process of book tie-ins, simultaneous social media campaigning and publicity events deployed on the publication of any significant children’s book now, Blyton was a one-woman marketing team.

Blyton lore has it that she answered every piece of fan-mail she ever received, paying attention to feedback from readers and parents and incorporating their wishes into her writing.

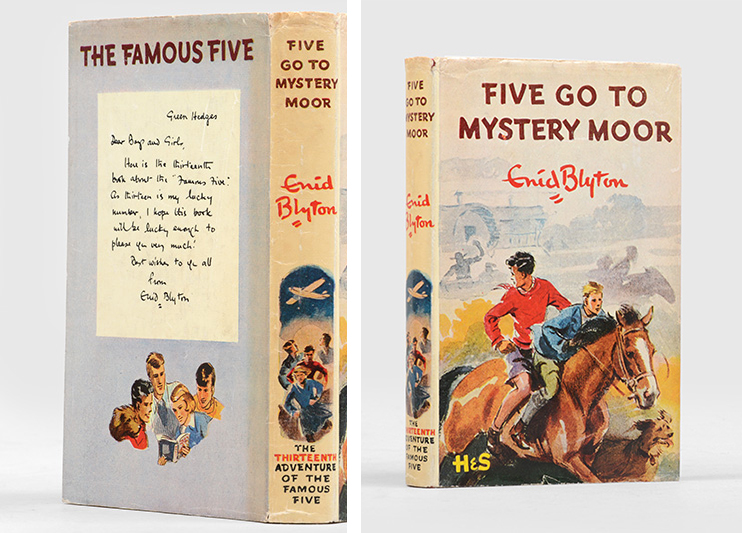

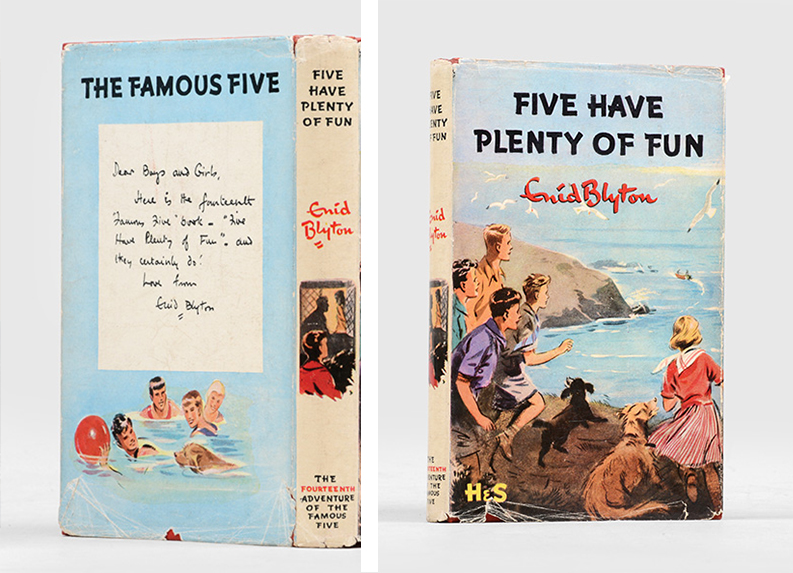

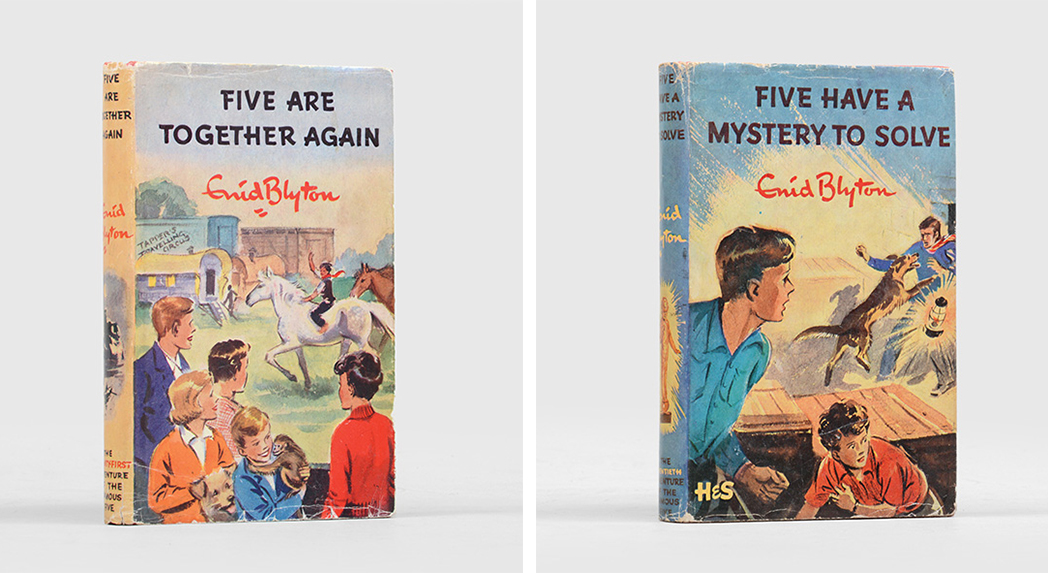

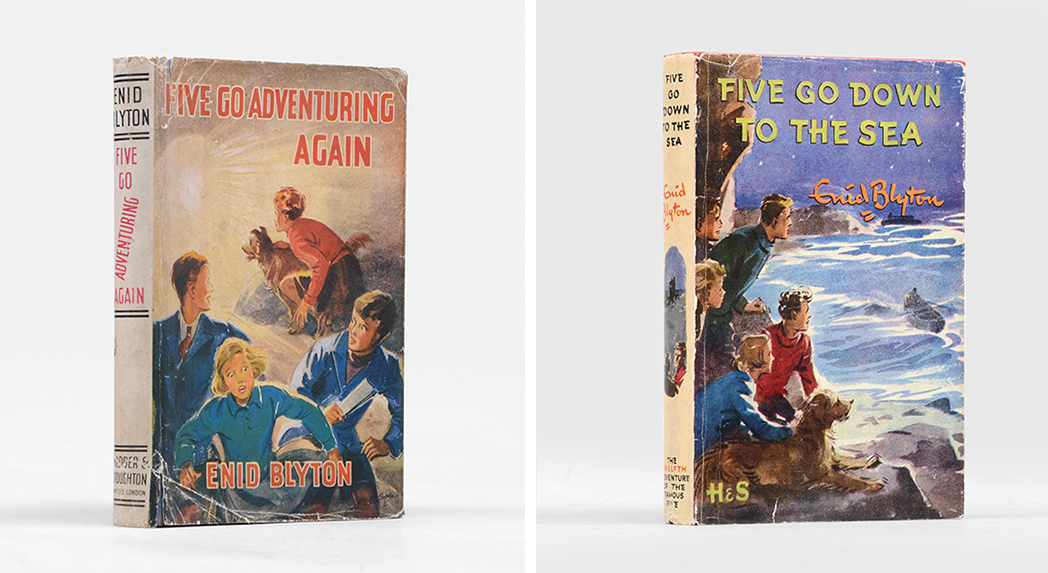

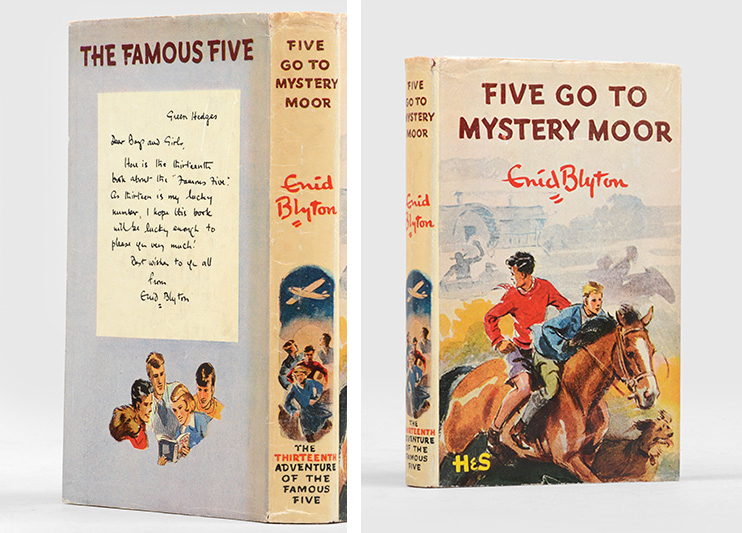

Short messages printed in her own handwriting and addressed directly to her readers began to appear of the dust jackets of each of her Famous Five novels, explaining for example, that many fans had asked for a novel entitled Five Go Down to the Sea so she had written one for them, or expressing her fervent hope that they will enjoy her latest offering. Blyton herself said, in a radio interview 1963, that “the most important quality I possess is my ability to get right to the hearts of children”.

Five Have Plenty of Fun, 1955. (BOOK SOLD)

Her apparent direct line into the child psyche, however, masks the sensibilities of a shrewd business woman. Her immense output – over 400 books in her lifetime – demonstrates an intelligent publication strategy, with different series written to correspond with successive reading stages, inviting children to progress from one to the next as their reading level developed.

She was also an early example of an author with an understanding of promoting her personal brand, overseeing the design of each book and ensuring that her distinctive signature, rather than simply a typed author name, was placed prominently on the cover of each book.

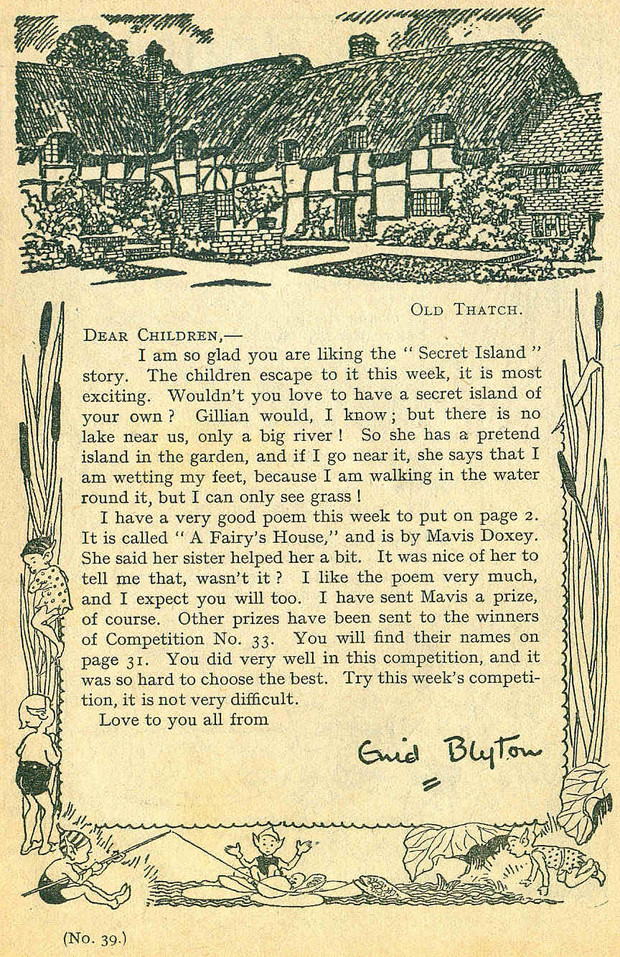

She started a weekly magazine, Sunny Stories, published between 1937 and 1953, with which she kept her fans fed with a steady trickle of Blyton content and in which she could address them directly in her characteristic cosy tone: “Dear Boys and Girls — … I am going to write your stories for you just as I have always done…What fun we shall have! I want you to help me too.”

From Enid Blyton’s Sunny Stories, No. 39, October 8, 1937 Image c/o The Enid Blyton Society.

She would occasionally reference her own daughters in these little letters to her fans – “Wouldn’t you love to have a secret island of your own? Gillian would, I know” – and her brand was built on her image as the perfect mummy, always in on her children’s games. The reality, it seems, was somewhat different. In 1989 Imogen, Blyton’s youngest daughter, published her memoir, A Childhood at Green Hedges, which paints a picture at odds with Blyton’s carefully cultivated public persona.

“The truth is, Enid Blyton was arrogant, insecure, pretentious, very skilled at putting difficult or unpleasant things out of her mind, and without a trace of maternal instinct…As a child, I viewed her as a rather strict authority. As an adult, I did not hate her. I pitied her.”

Blyton also apparently carefully stage-managed her divorce from her first husband to limit any damage to her reputation, making a deal with him that if he would agree to let her divorce him quietly, she would grant him access to their children. For whatever reason, however, this bargain was not upheld, and neither of the girls had any relationship with their father after the divorce.

Five are Together Again, 1963 – BOOK SOLD

Speculators have wondered whether Blyton’s ability to communicate so successfully with her young fans and her seeming disinterest in her own family might be a consequence of her own child-like personality. Her books create a childhood idyll of sunny days, bike rides through unspoiled English countryside, low-stakes adventure and plenty of good things to eat – a safe world in which to forget the troubles of real life. Some accounts suggest that Blyton’s escapist narratives were created for herself as much as for her readers – that she preferred dreaming up new japes for Julian, Dick, Anne, George and Timmy than engaging in the escapades of everyday domestic life. Her child-like imagination could apparently sometimes manifest itself as childish impatience and temper.

“Her approach to life was childlike, and she could be spiteful, like a teenager” says Imogen in Green Hedges.

Nevertheless, Blyton’s books seem to capture something essential in the imaginations of children and the basic ingredients of her books – escapism, fantastical and idealised worlds, adventure, a lack of adult supervision – still form the mainstays of children’s fiction. An attempt to deal with some of the weightier criticisms of her work – her outdated language and attitudes – saw her current publisher, Hodder, make plans to overhaul the text, which would have seen “housemistress” becoming “teacher”, “awful swotter” becoming “bookworm”, “mother and father” becoming “mum and dad” and “tinker” becoming “traveller”. However, these plans were abandoned due to the negative feedback they received from readers on the updated versions and Blyton’s original text, warts and all, has prevailed.

Five Go Adventuring Again, 1943. (BOOK SOLD)

Five Go Down to the Sea, 1953. (BOOK SOLD)

Recent Comments