Balmorality: the romanticisation of Scotland

A glance at any packet of shortbread will probably tell you that the romanticised myth of Scotland is alive and well; brooding heather covered landscapes, noble stags, swathes of tartan and claymore-toting clan chieftains still form the mainstay of stereotypical Scottish imagery. These persistent symbols of Scottishness, while seemingly drawing their aesthetic inspiration from a bygone age of clans, ceilidhs and castles, actually didn’t enter the cultural consciousness until the eighteenth century, filtering down from an increased interest in Scotland by the British monarchy. ‘Balmorality’, a term named for Queen Victoria’s Scottish residence to reflect her general embrace of Highland life, encompasses the arguably superficial enthusiasm for all things sterotypically Scottish which has emerged both in Britain and throughout the rest of the world over the past two centuries.

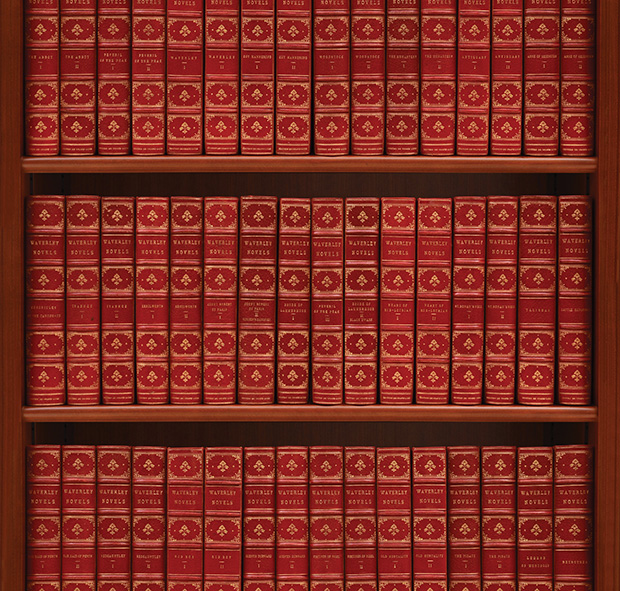

The romanticisation of Scotland can be most definitively linked in literature with the Waverley novels of Sir Walter Scott. The first of the Waverley novels was published in 1814 and was set during the Jacobite uprising which took place almost a century earlier. The novels were so popular that Scott was propelled to fame, and was invited to dine with King George IV, (then Prince Regent). When, several years later, the Scottish ‘Radical War’ of 1820, inspired by the American and French Revolutions, caused King George to plan the first royal visit to Scotland in over two hundred years in an effort to quell unrest, it was Scott he called on to carefully stage manage the visit. By now a baronet with numerous valuable connections to Scottish nobility, Scott saw the opportunity both to avert an uprising and to promote highland culture. He reasoned that, because of George’s lineage, the king could legitimately claim as much Stuart heritage as Bonnie Prince Charlie and could thus present himself as a Jacobite prince, properly accoutred Royal Stuart tartan. Kilts at this time were no longer generally worn, having been banned by the Dress Act of 1746, which made the wearing of ‘Highland dress’ illegal. Though the act was repealed in 1782, kilts had only come back into fashion with the Scottish gentry, a number of whom set up ‘Highland Societies’; clubs for landowners which championed (along with what they called “improvements’ –the Highland Clearances) “the general use of the ancient Highland dress” at meetings. Scott was the enthusiastic chairman of just such an association – the Celtic Society of Edinburgh – and attended meetings in “the garb of old Gaul”. For the king to appear so attired was not only an attempt to appeal to the heritage of the Scottish people but also to gloss over old wrongs.

George’s visit sparked an interest in Scottish dress, and, in its wake, the demand for kilts grew so high that Scottish weaving mills were unable to cope with the demand. It was in this period that (contrary to the generally assumed belief that individualised tartans are a much older tradition) many of the clan tartans were designated.

Complete in 48 volumes, edition de Grand Luxe of Walter Scott’s Waverley Novels, number 352 of 500 super-deluxe sets. Estes and Lauriat also issued an “edition de luxe” of 1,000 sets, though this is the far grander and more limited edition, presented here as a magnificently bound library set. Though the bookplates in this set are numbered, sequentially, vols. 16-63 (presumably because Frederick E. Reed had 15 other volumes, not included here, of Scott’s poems and works from different editions bound with these Waverley Novels a single library set), this set nonetheless constitutes Estes & Lauriat’s Edition de Grand Luxe of Scott’s Waverley Novels, complete as issued.

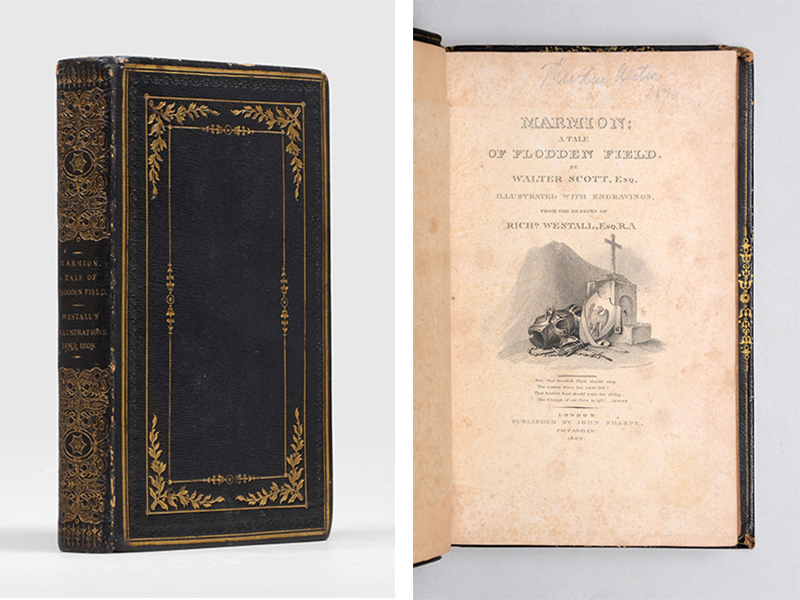

First edition thus, the first illustrated and first London edition (Marmion was first printed in Edinburgh in 1808) of Scott’s 16th-century Scottish tale, here embellished with engravings by Richard Westall, and this copy exquisitely bound by Taylor & Hessey.

New edition of this collection of landscape illustrations from Walter Scott’s popular series of novels. Each plate is accompanied by an excerpt from the text and explanation of the image by the artist. Contributors include G. Cattermole, P. Dewint, J. D. Harding, and G. F. Robson, amongst other successful landscape artists, their work etched by the Findens with the “elaborate finish and precision for which their work had become known” (ODNB).

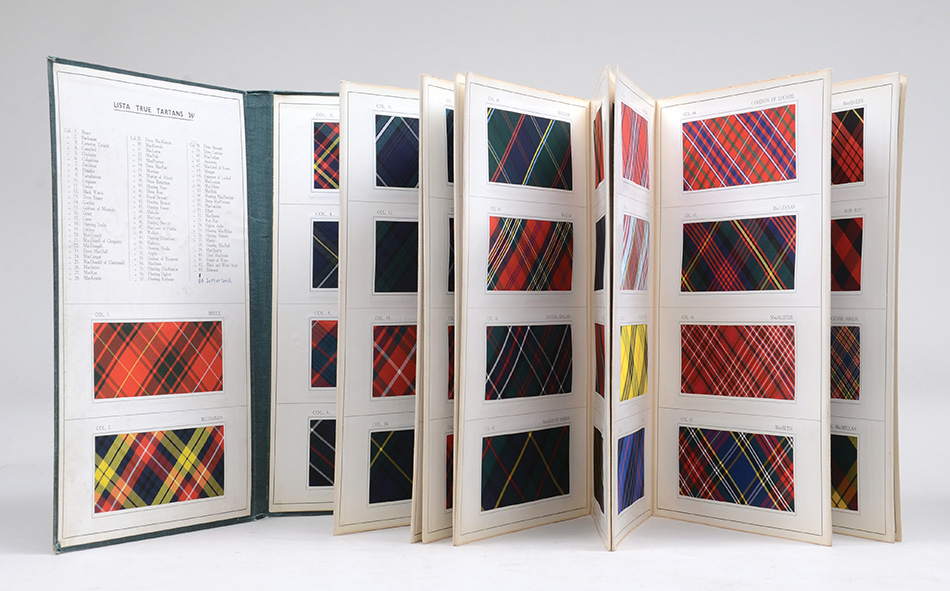

Lista True Tartans, c. 1920. (Item sold)

Wonderful sample books for “true” tartans, that is fabrics woven with accurate thread counts to match the approved sett or pattern for recognized clan tartans. A total of 146 identified tartans are represented by fabric swatches, rectangular in one volume, triangular in the other, both of around six inches in length so we presume that the full sett is shown in the examples. Lister’s Manningham Mills, based in a superb high Victorian Italianate building with campanile-chimney, was the largest silk factory in the world, at its height employing 11,000. They were suppliers of highest quality fabrics, for example providing 1,000 years of velvet for George V’s coronation. With the rise of foreign competition, and the prevalence of artificial fibres the business collapsed in the 1990s, the Grade II” listed building has been renovated and converted into apartments.

The popularity of the romanticised view of Scotland, along with the natural association of the British monarchy, endured throughout the reign of William IV, George’s successor, and was solidified by Queen Victoria who, perhaps more than any other single person, promoted a vision of Highland culture and an international enthusiasm for Scottish tourism, which for good or ill, has endured to the present day.

In 1847, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert acquired the Balmoral estate in Aberdeenshire. Balmoral castle was commissioned in 1852 the replace the original house, which was deemed too small for a royal residence. The design was to be a consummate example of Scots Baronial architecture, though it was amended personally by Prince Albert who apparently held very specific opinions about details such as turrets and windows. As a consequence, it has been judged by some as having a slightly Germanic look (unsurprising, as the surrounding landscape of Deeside was itself chosen partly because it reminded the royal couple of Albert’s homeland of Thuringia in Germany). The melding of architectural styles had an undeniably romantic effect – crow-step gables, battlements, towers and crucifix arrow slits giving the impression of a small fortified keep long past the time when such features served any practical purpose. The interior of the house was decked out almost in a pastiche of Scottish baronial style, with copious amounts of tartan and numerous game trophies.

Victoria and Albert took great delight in their Scottish residence, commissioning numerous painters to capture aspects of the house and estate over the years and personally overseeing the management and development of the land. After Albert’s death in 1861, it was to Balmoral that Victoria increasingly retreated, taking solace in the isolation and the Highland culture she had come to feel an affinity for. Long before the purchase of Balmoral, Victoria had been an avid reader of Scott, and had a healthily developed appreciation for the picturesque aspects of peasant life that were a feature of the wider Romantic Movement, and which found full expression in her admiration of what she saw as the simple and honest life of the tenants of her estate. It was also at Balmoral that Victoria began her controversial friendship with John Brown, the servant whose exact relationship with the queen is still discussed with avidity.

R. R. McIan, Lithographs from Clans of the Scottish Highlands, 1845.

James Logan’s Clans of the Scottish Highlands was the first illustrated work depicting and describing each clan, along with its history and tartan. The work was dedicated to Queen Victoria. McIan was primarily an actor, as well as a Highlander and “fierce Jacobite”, and his theatrical background is evident in his depictions of Highland costume.

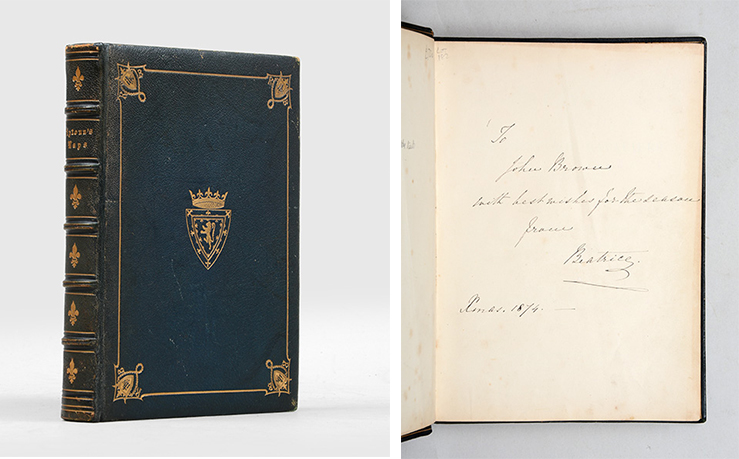

Edmondstoune William Aytoun, Lays of the Scottish Cavaliers, 1870.

Presentation copy from Victoria’s favourite daughter, Princess Beatrice, to the queen’s favourite servant, John Brown, inscribed by the princess on the front blank, “To John Brown, with best wishes for the season, from Beatrice, Xmas. 1874”. An intriguing association: Brown (18261883) had been a significant feature in the royal household for the majority of Beatrice’s life, having been selected by Prince Albert to be Victoria’s personal servant in Scotland in 1858. The Scotsman quickly became indispensable to Victoria after Albert’s death in 1861, becoming the cause of salacious gossip and familial tensions. Beatrice (18571944) is often considered to have been the closest of Victoria’s children to Brown, spending considerable time in his company, notably in Balmoral, and helping him to carry out her mother’s wishes in her role as “the prop, comfort and companion” of Victoria. Victoria found solace in both Beatrice and Brown after Albert’s death, being “over-protective of her ‘Baby’ until she was well into adult life” (ODNB).

Aytoun’s Lays, first published in 1849, are modelled on the works of Macaulay and Scott and “became important texts in the romantic revival in mid-Victorian Scotland”, a movement which Victoria’s passion for Scotland, first fired by her 1842 visit with Albert, did much to encourage (ibid.). Indeed Queen Victoria was presented a copy of an earlier edition of the same work by Prince Albert, later Edward VII, and his wife Alexandra, in 1865.

In imitation of the Queen, Scotland became a fashionable Victorian holiday destination, creating a thriving tourist industry which endures today. A few aesthetic aspects of Highland life beloved by Victoria – tartan, mountainous landscapes, bagpipes and traditional dancing – have inevitably become synonymous with the whole of Scotland in the eyes of the rest of the world. Inspiring, conversely, both rallying points for national pride and ire at the reduction of the diverse culture of a nation to ‘tartan kitsch’, this romanticisation of Scotland remains a part of the ongoing conversation about Scottish national identity shaping British politics today.

Recent Comments