A Noble Visage: The Famous Droeshout Portrait of William Shakespeare

The engraving that graces the frontispiece of the first Four Folios is one of the most recognizable portraits in human history. It holds a profound relevance bordering on an almost religious quality. It is also one of the few depictions of Shakespeare that scholars have widely agreed legitimately shows what Shakespeare looked like, but the question remains, where does this image come from and what makes it such a reliable source for depicting Shakespeare’s appearance?

The Chandos Portrait: A Potential Inspiration for the Engraving

The Droeshout engraving holds many similarities with an earlier portrait of Shakespeare known as the Chandos Portrait. Painted during Shakespeare’s lifetime sometime between 1600 and 1610, the Chandos Portrait is one of the two most famous portraits that are believed to depict Shakespeare. It is named after the 3rd Duke of Chandos who was a former owner of the painting which now sits in the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Although it is not possible to determine with certainty who painted the portrait, the most likely candidate is an English painter, John Taylor, a respected member of the Painter-Stainers’ Company who was described in a note written in 1719 by George Vertue as Shakespeare’s “intimate friend’. Due to the similarities between the oil painting and engraving, it has been strongly suggested that the Chandos Portrait served as a reference for the later engraving which was created after Shakespeare’s death.

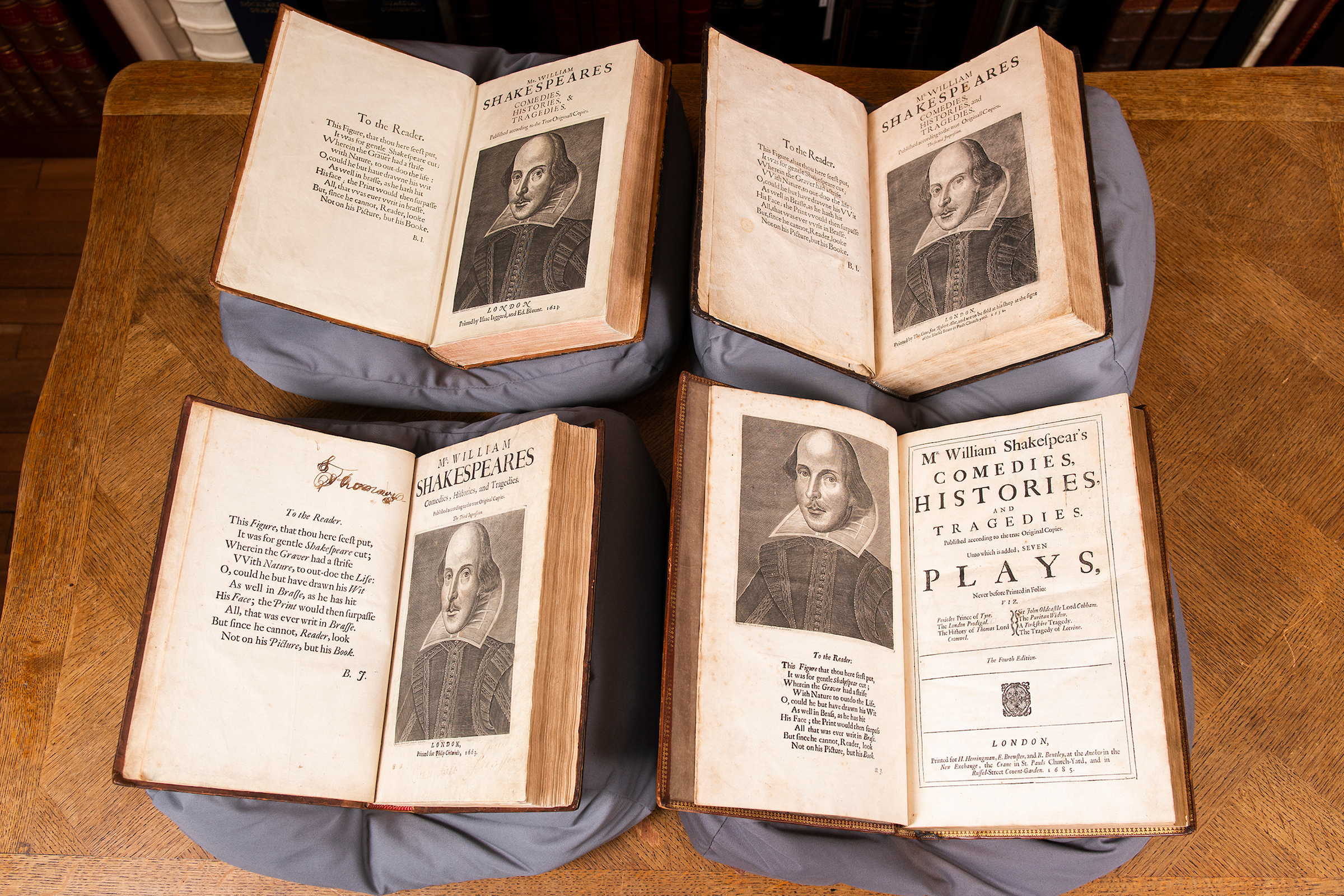

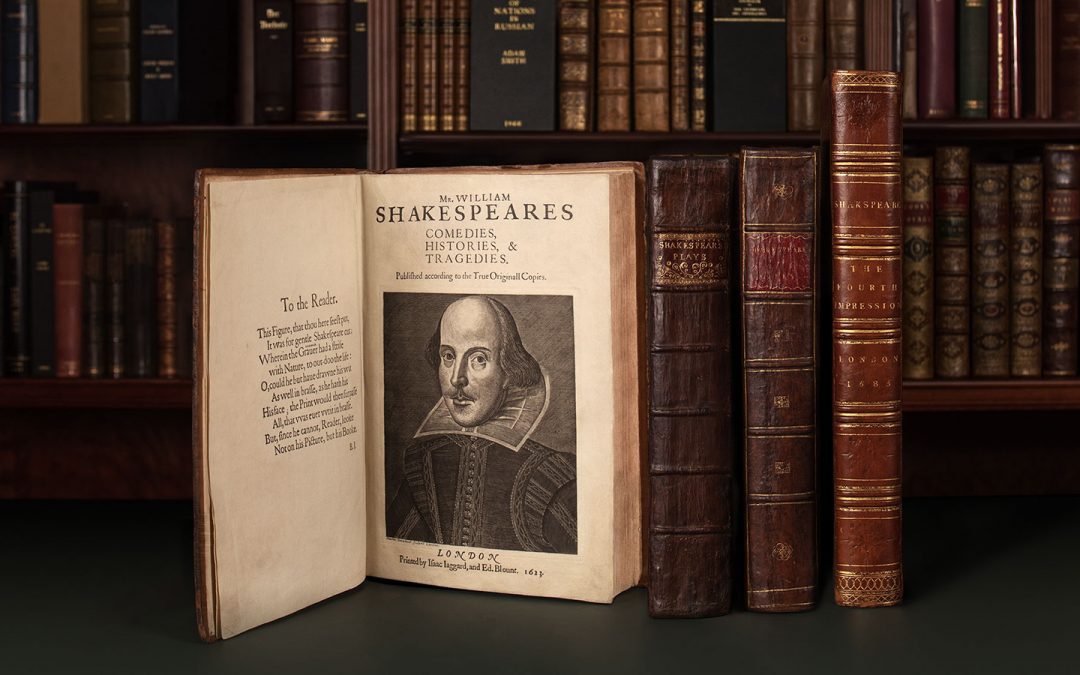

The Droeshout Portrait in all Four Folios

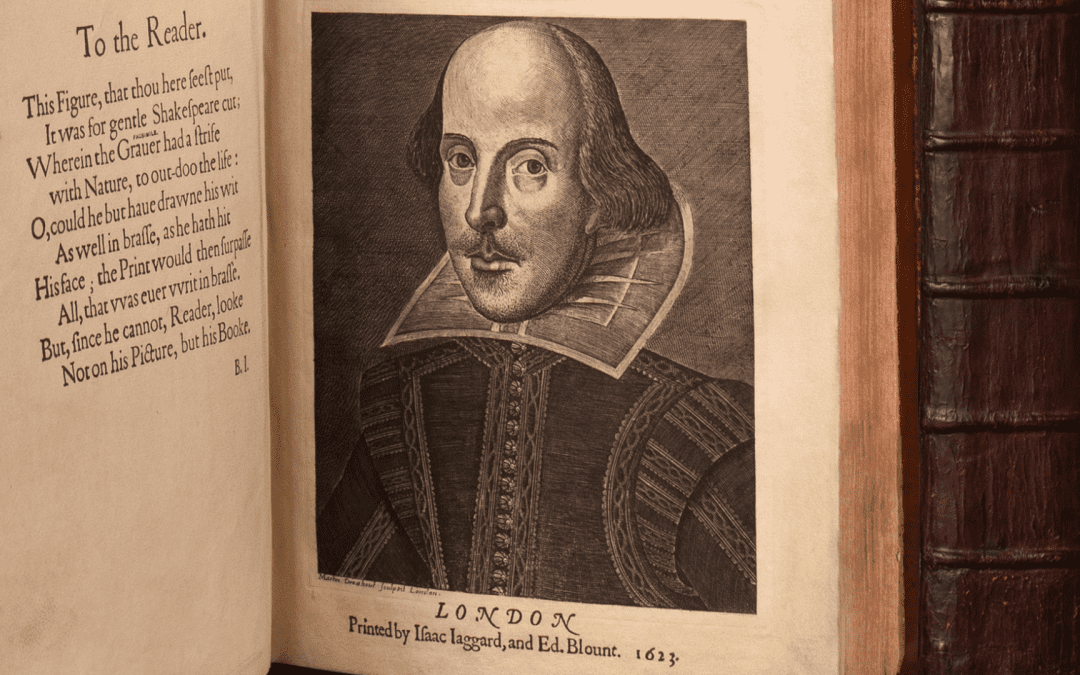

The Droeshout Portrait is depicted on the frontispiece of all Four Folios and is printed alongside a poem To The Reader by Shakespeare’s friend Ben Jonson in which he praises the accuracy of the engraving’s likeness stating that the engraver has managed to “outdo the life” and has “hit his face” accurately, failing only in managing to depict Shakespeare’s wit for which the reader will have to read the plays collected together in the folio.

In contrast to the Chandos Portrait which depicts Shakespeare as a distinctly bohemian figure with an earring dangling from his ear, much more the image of a Elizabethan playwright and poet, the Droeshout portrait squeezes him into formal court costume, which has the effect of making Shakespeare look somewhat stiff and unnatural. That has led some people to question the authenticity of the Droeshout Portrait however Jonson knew the playwright well and vouched for the portrait’s resemblance to his good friend.

There are distinct versions of the portrait, or what is known as “states”, printed from the same plate by Droeshout himself. There are only four examples of the first state making it exceptionally rare. It is very likely that the first state was used as a test printing by the engraver so that he could see whether any alterations needed to be made to the engraving. For most copies of the First Folio, and for all copies of the subsequent folios it was the second state which was used. This had some changes from the first state including heavier shadows and minor differences in the jawline and moustache.

As a whole, the portraits in each of the first Four Folios appear to be the same with the exception of the Fourth Folio where the portrait has been placed on the opposite side above Ben Jonson’s poem across from the frontispiece. While to some the portrait appears smaller than it looks in the other Folios, this is simply not true, as the same engraving plate was used for all four of the Folios. It is simply an optical illusion caused by the re-location of the portrait from where it was originally placed in the other Folios.

The Other Portraits of Shakespeare

There are many other portraits claiming to be depictions of Shakespeare that were created either during his life, or within living memory. Many of these are claimed to have been painted from life, The Chandos Portrait being the most legitimate. The two depictions that have been unambiguously stated to represent Shakespeare are both posthumous. One of these is the Droeshout Portrait and the other is the bust in Shakespeare’s funerary monument at Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-Upon-Avon.

Of the other 15 or so portraits that claim to be of Shakespeare either the sitter is unidentified, or the depiction is debatable. For instance, the Soest Portrait, which was painted 20 years after Shakespeare’s death is said to have been painted from a man who looked like Shakespeare and not Shakespeare himself. The Chesterfield Portrait, another posthumous depiction of Shakespeare is generally assumed to be based on the Chandos Portrait, which indicates that the Chandos was accepted as being representative of Shakespeare within living memory of the Bard.

Recent Comments