As custodians of unique and rare treasures, nothing makes us more proud than finding them the right home. We look fondly at many examples, but these memorable sales in 2023 made us especially proud.

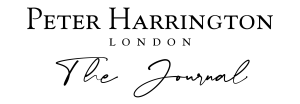

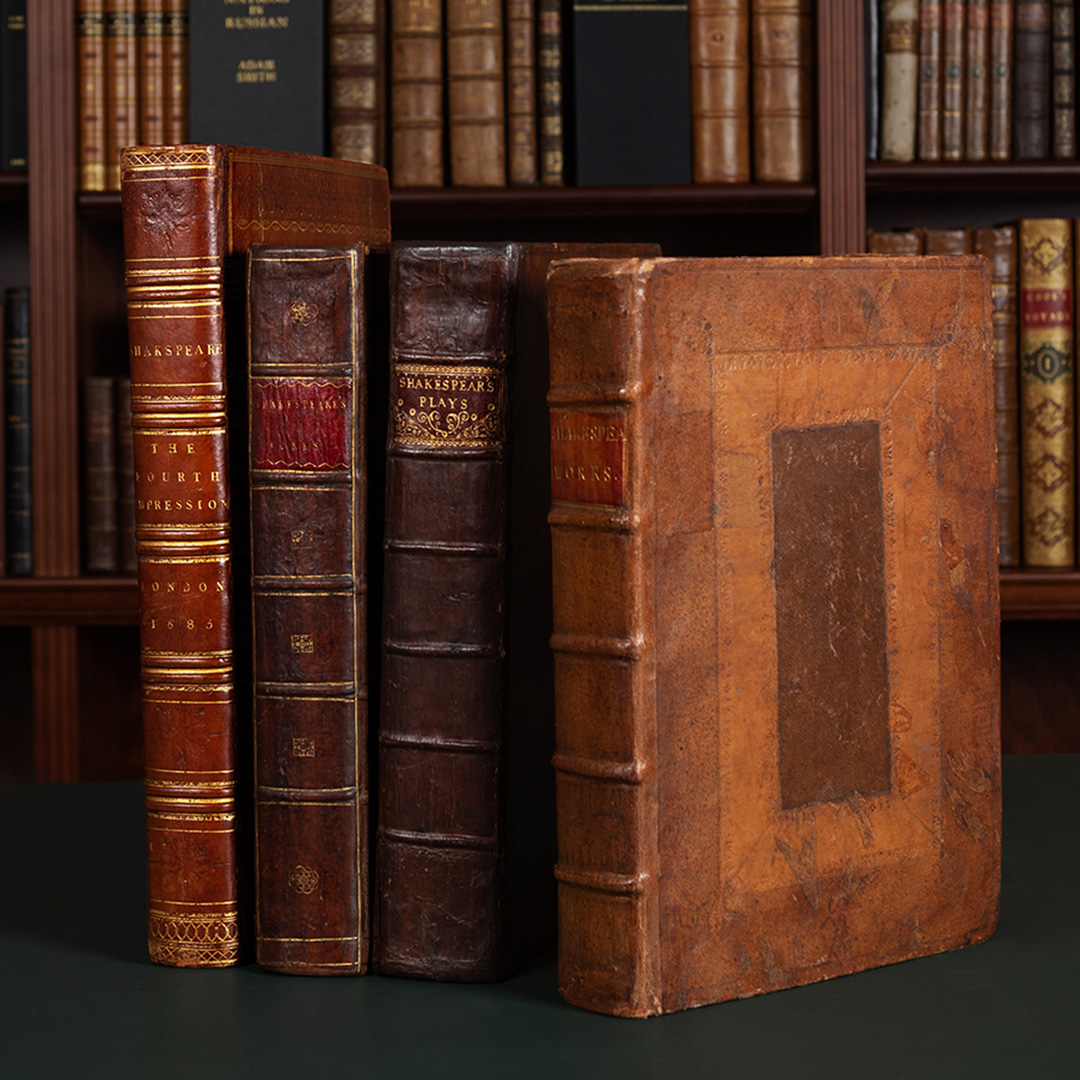

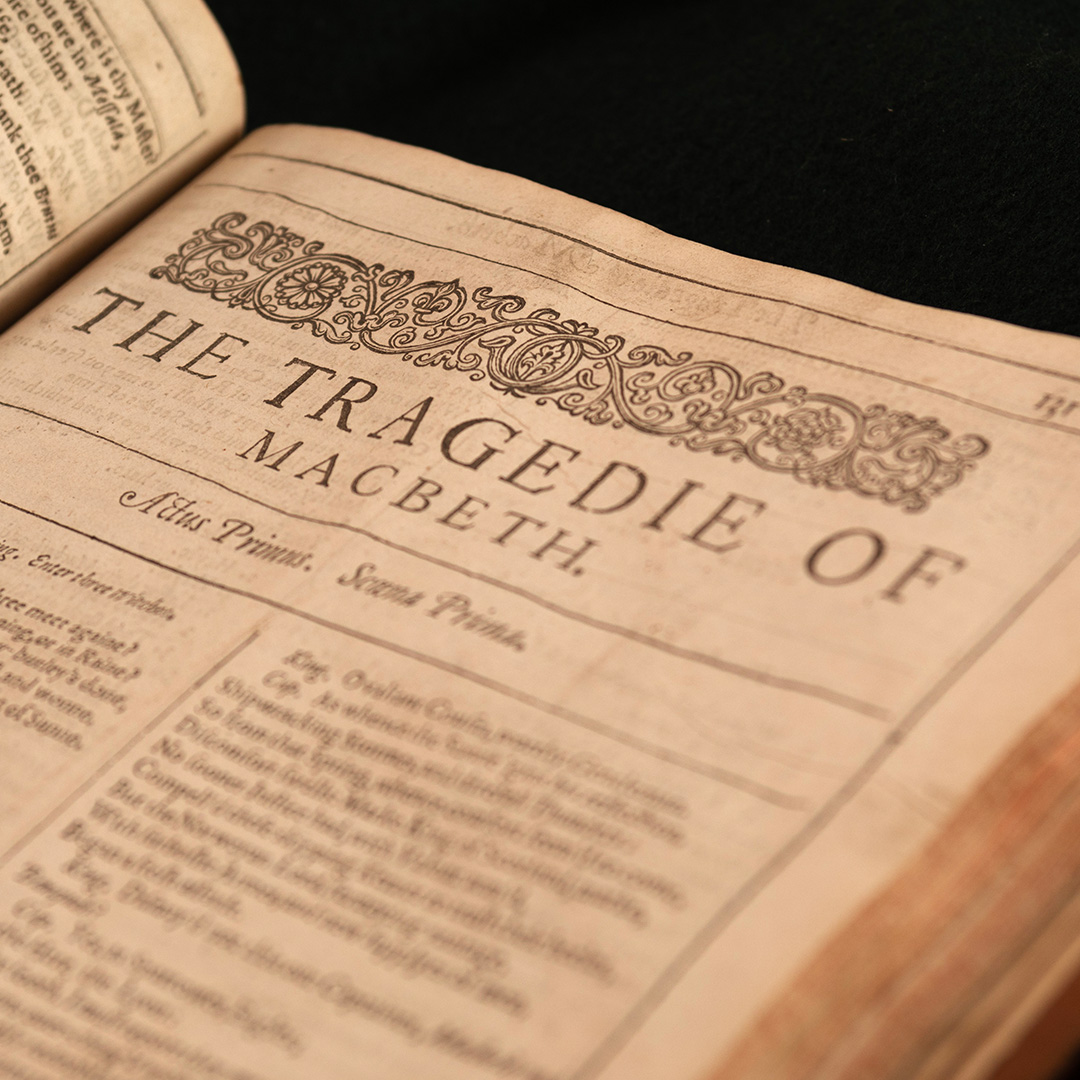

SHAKESPEARE, William. First Folio, 1623.

The year was the occasion for worldwide celebrations of the 400th anniversary of the first publication of the Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies of William Shakespeare, commonly known as the First Folio. As the book was published in an edition of probably 750 copies in November 1623 and more than 230 copies survive, some cynics argue it is not truly rare. But most of these copies are now off the collectors’ market, carefully guarded in institutional holdings, and those few that come to market are typically sold at auction. And few could deny that the First Folio is one of the most iconic books in English or indeed world literature.

So, it was a rare treat for us as booksellers to be able to offer for sale a copy of the First Folio, which we publicized in a slim catalogue issued in time for Shakespeare’s birthday, together with all three of the succeeding 17th-century Shakespeare folios and the 1640 Poems.

The copy of the First Folio we offered was a splendid copy bound in English panelled calf, from the library of Lord Hesketh at Easton Neston. Like virtually all surviving copies, it has imperfections: in this case, four of the eight preliminary leaves are skilfully supplied in facsimile. In all other respects, it is a remarkably fine copy. Having the book in our possession gave us a first-hand education in the finer points of the make-up and production of this ever-fascinating volume.

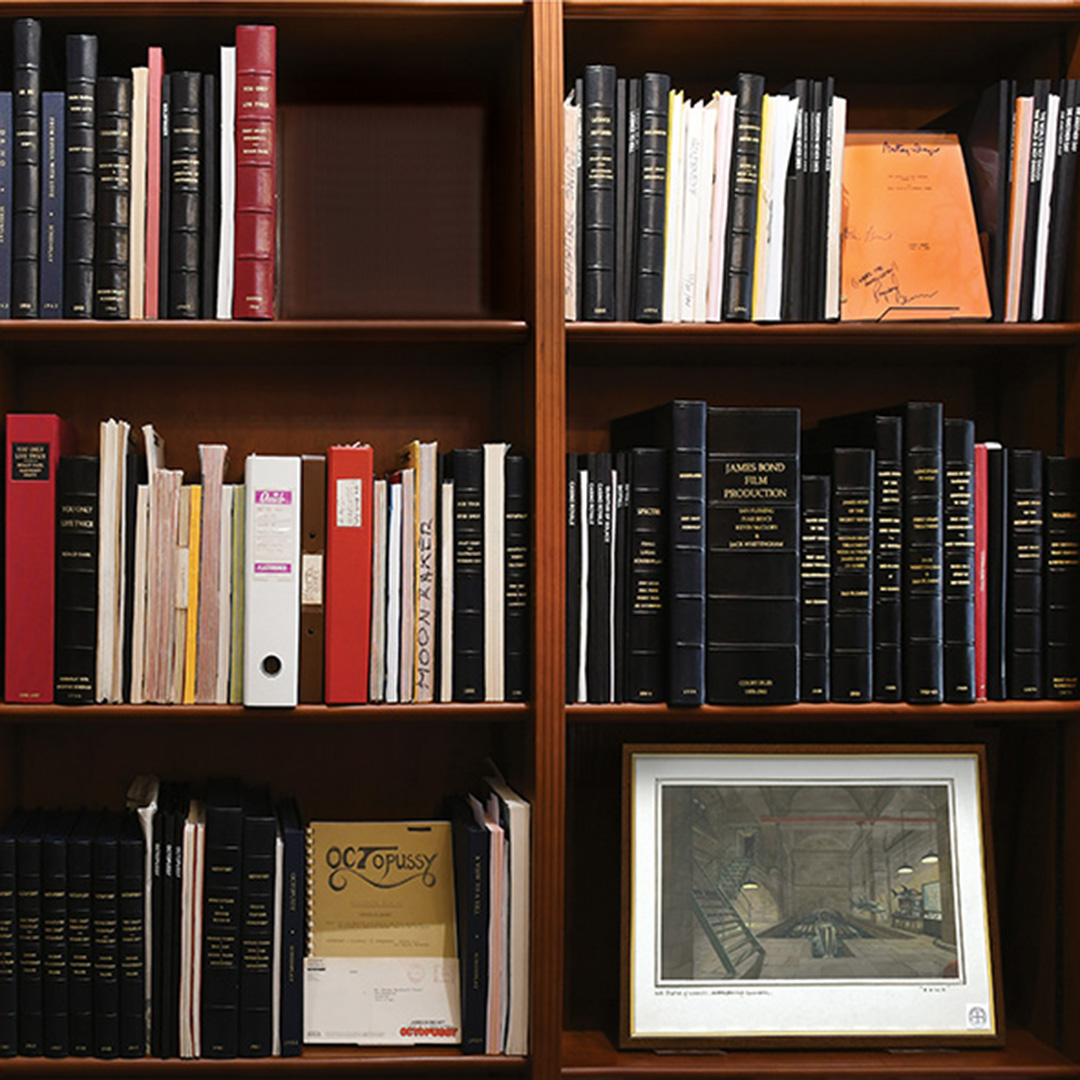

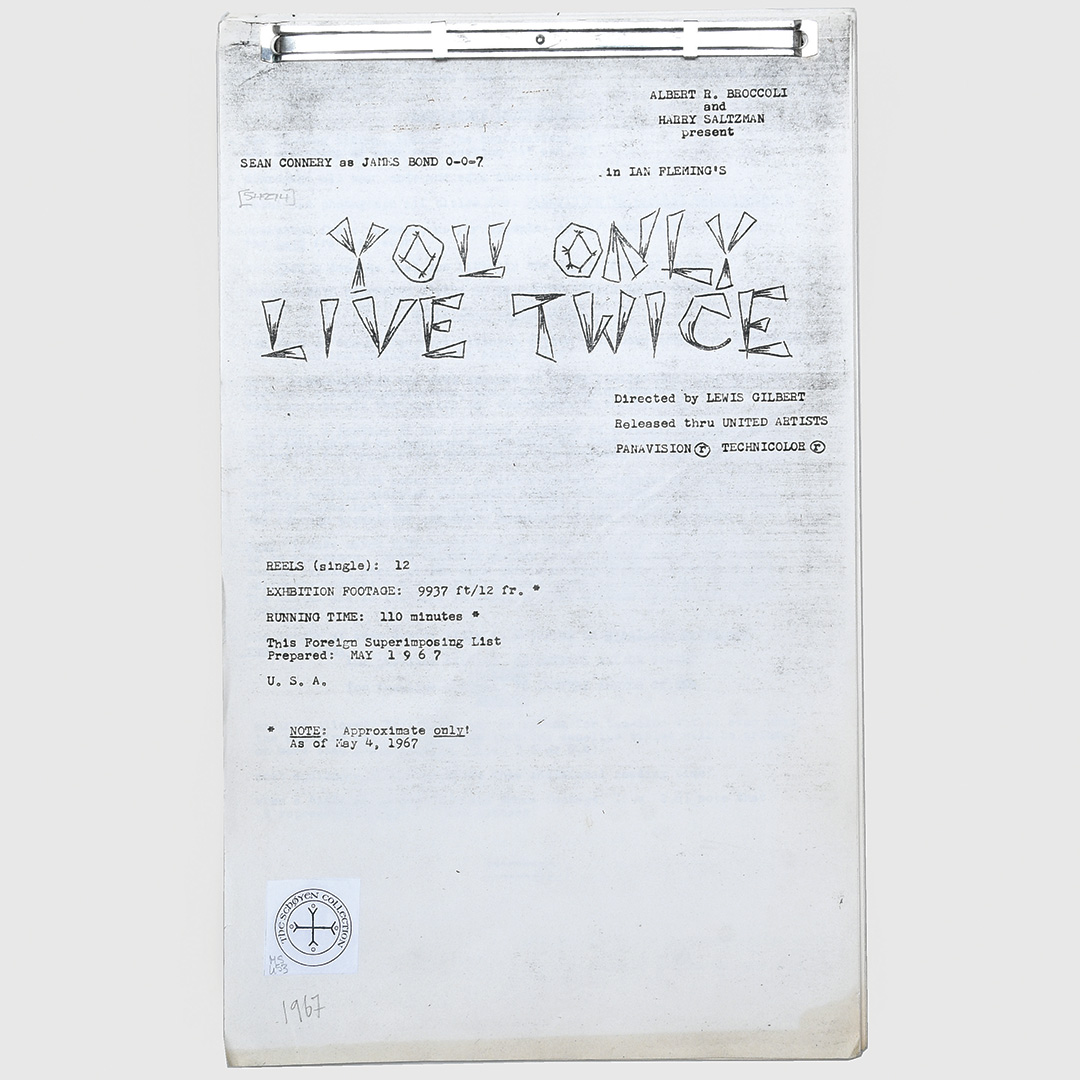

FLEMING, Ian. Collection of original James Bond screenplays, film scripts, and storyboards. 1962-2014.

Another item we sold this year centred on the transition from page to screen of the 16 James Bond books written by Ian Fleming. The collection of 119 items we sold in 2023 was a comprehensive assembly of film scripts, screenplays, manuscripts, storyboards, costume designs, publicity material, and production notes, tracing the story of Bond on film from Dr No in 1962 through to Spectre in 2014.

Besides the unparalleled series of items relating to the canonical EON Productions film series, the collection includes significant material from other film studios, including the spoof Casino Royale, Never Say Never Again, and Chitty, Chitty, Bang, Bang.

Some highlights include Wolf Mankowitz and Richard Maibaum’s earliest draft screenplay for the first Bond film, Dr. No (1962); extensive material and correspondence concerning the controversial creation of the film Thunderball (1965); an unused film treatment written by Fleming himself entitled James Bond of the Secret Service; and much more.

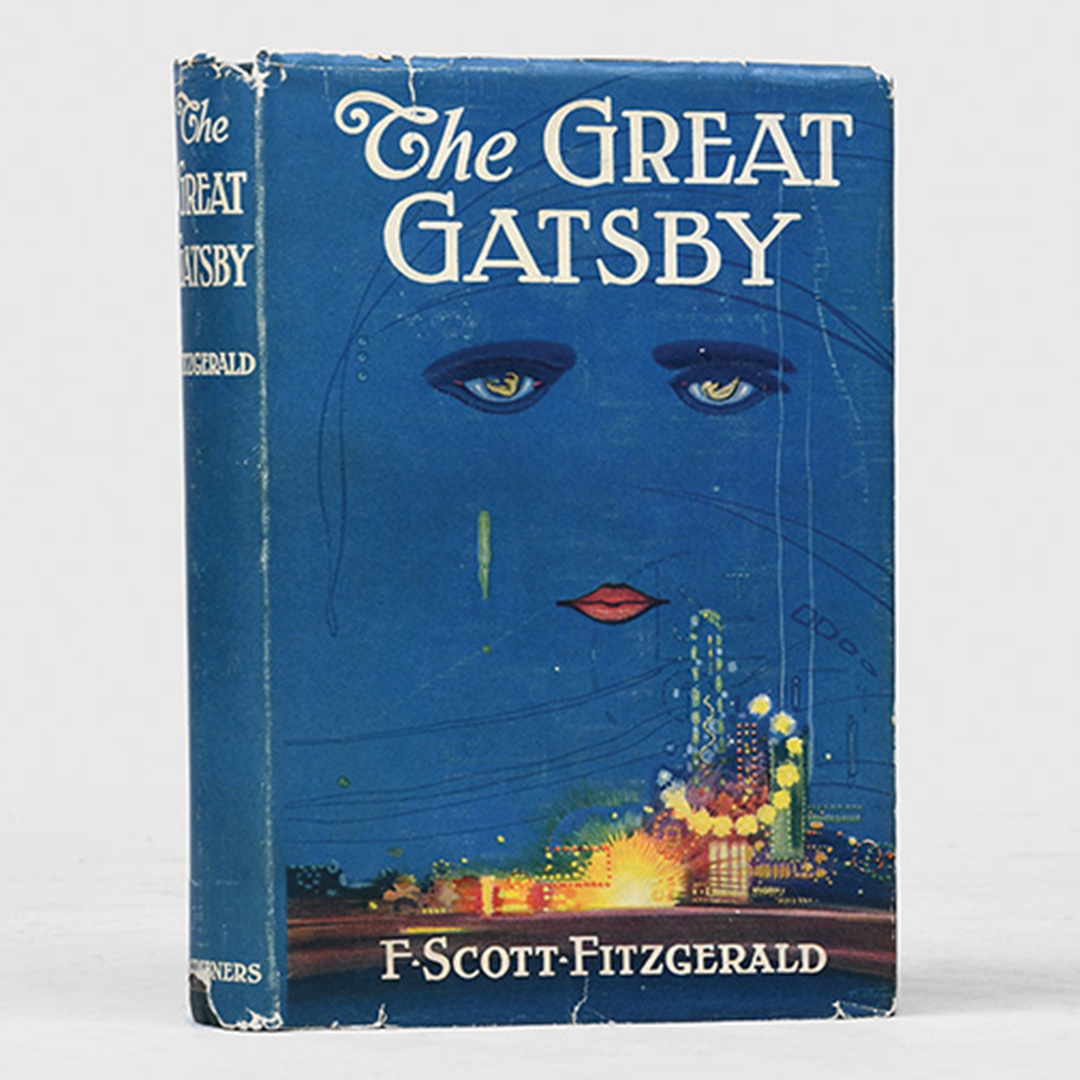

FITZGERALD, F. Scott. The Great Gatsby, 1925.

Sometimes a modern book is just a book, but when it’s F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby in the original dust jacket, it’s quite a book. The copy we sold this year had been through our hands before, and it’s a humdinger, from the collection of the late Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts, a friend of the firm and a true gentleman, much missed by us all. The spectacular Gatsby jacket dates from 1925, the hinge point when dust jackets got interesting, moving away from plain paper or simple one-colour tints to truly creative full-colour graphic creations. The dust jacket is the only known work in this format of the Cuban American artist Francis Cugat. In a famous incident, Fitzgerald caught sight of Cugat’s design in its early stages and wrote some elements of it into his story, a surely unique example of the dust jacket design influencing the composition of a novel.

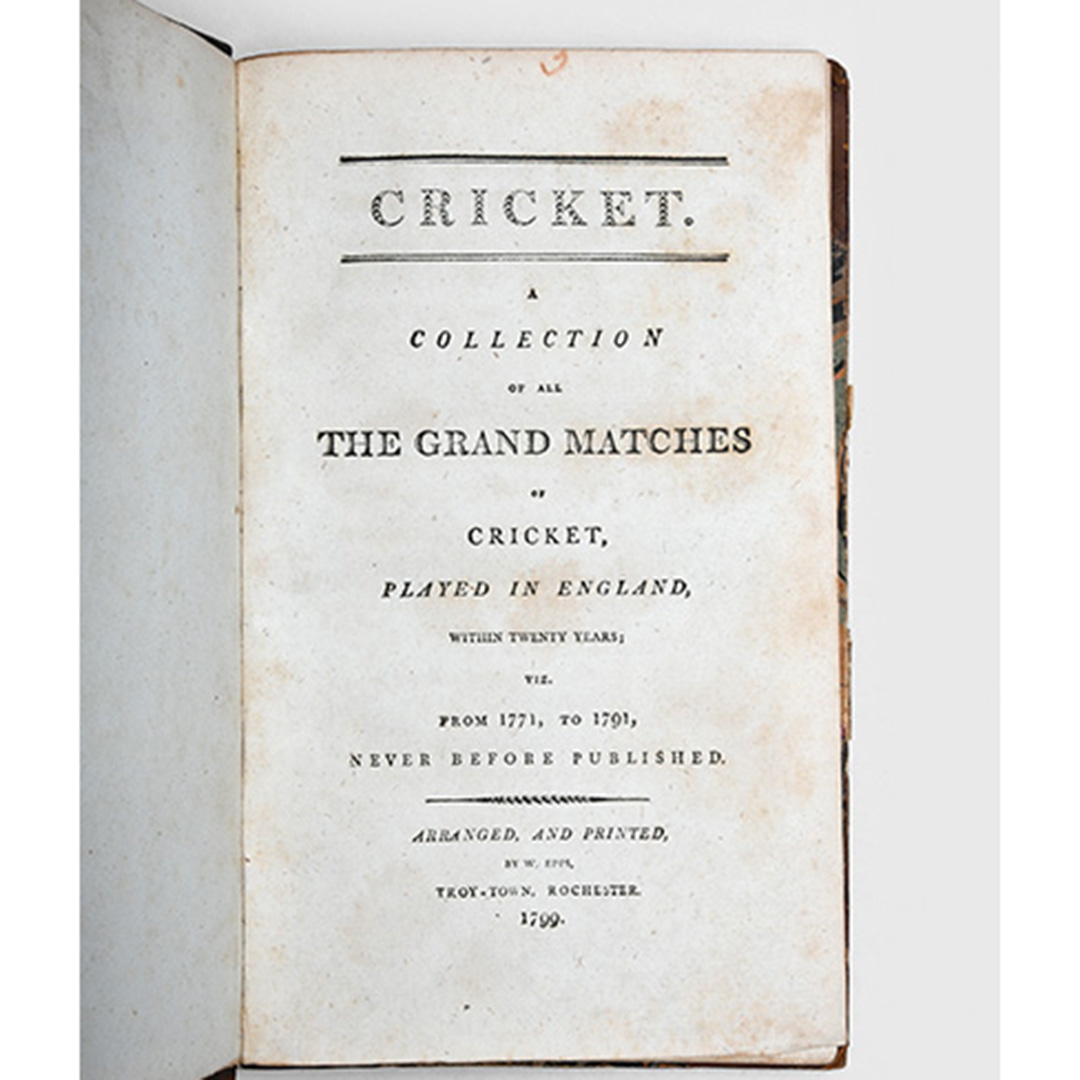

EPPS, William. Cricket, 1799.

Among his many other interests, Charlie Watts was fond of cricket, and he would have appreciated another of our sales this year. William Epps was a keen cricketer in Kent at the end of the 1700s. Like many cricket enthusiasts, Epps relished statistics. Cricket scores from 1790 onwards were recorded in annals compiled by Samuel Britcher, the MCC’s first official scorer. Epps travelled around England collecting earlier scorecards to compile a work to fill the gaps Britcher had left behind, which was published in 1799 with the self-explanatory title, Cricket; A Collection of All the Grand Matches of Cricket played in England within Twenty Years, viz. from 1771 to 1791, never before published. Without Epps’s efforts, these matches would surely have remained forgotten forever.

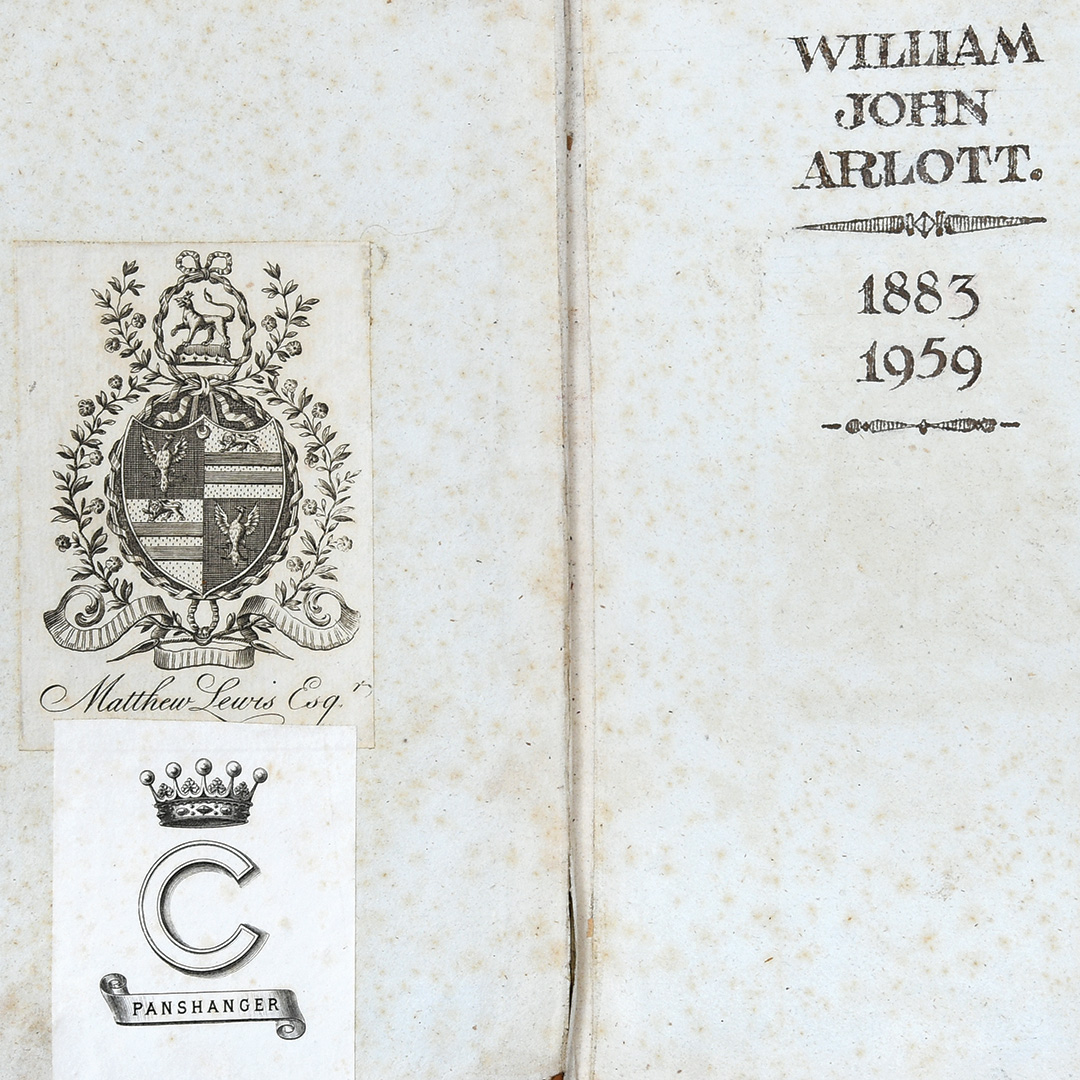

Self-printed in his hometown of Troy Town, Rochester, Epp’s book is a legendary rarity among cricket collectors, and this copy was from the library of the famed cricket commentator, John Arlott. When we advertised the book for sale, we noted the British Library did not have a copy. One of our clients decided this was an omission he wished to remedy, and so he donated the money to buy the book from us on behalf of the British Library.

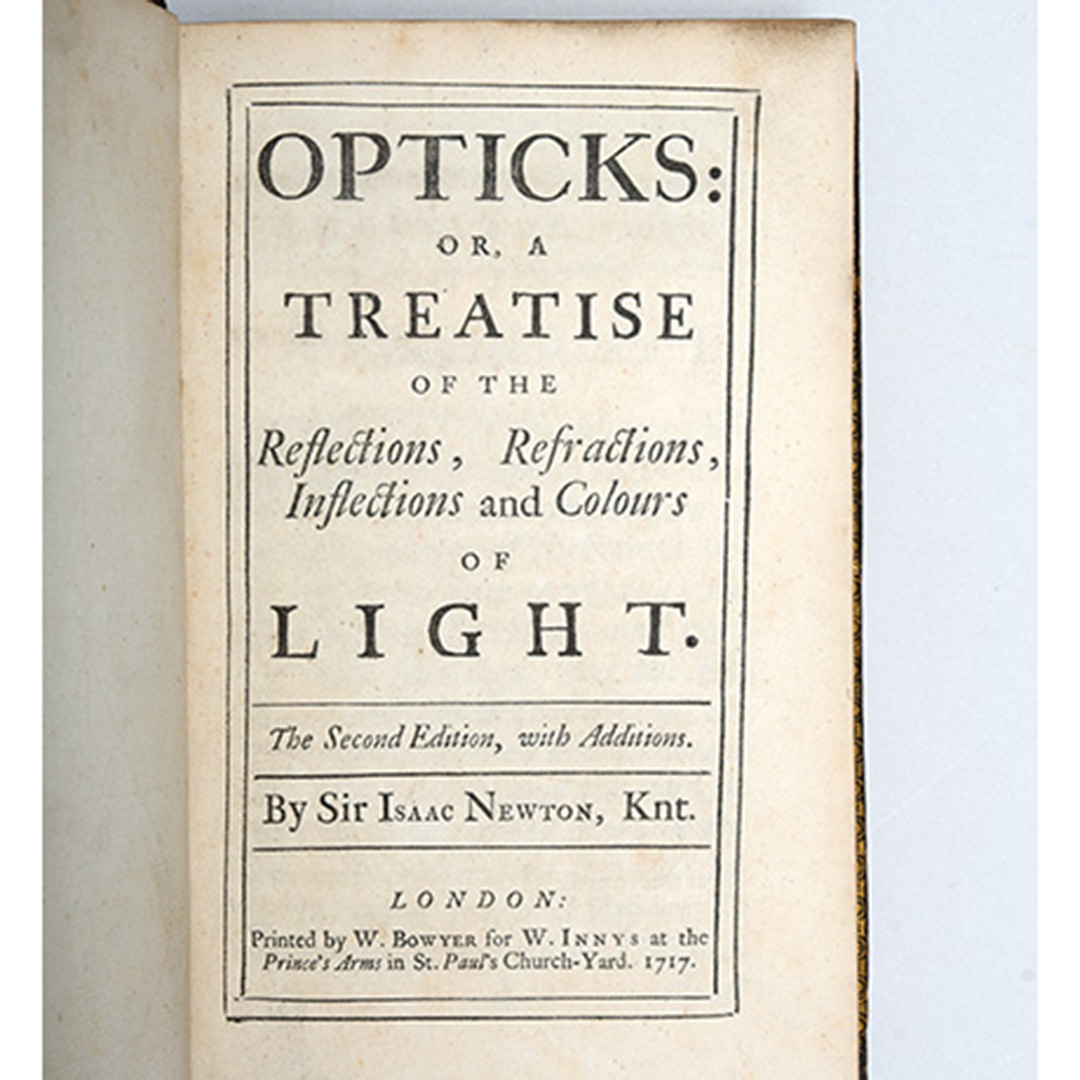

NEWTON, Isaac. Opticks, 1717.

At least in our experience, such an unexpectedly generous donation is a once-in-a-lifetime event, and the collector who unearthed Isaac Newton’s own copy of the second edition of his Opticks, which we also sold this year, felt much the same.

The story of Isaac Newton’s library is complicated because he died without leaving a will. His possessions were sold, including his books, which were purchased en bloc for £300 by the warden of the Fleet Prison as a gift for his son, an Oxfordshire rector. The books stayed in the rectory and became the possession of Dr James Musgrave, before being removed to Barnsley Park, Gloucestershire, the home of his son, Sir James Musgrave, Bart, where the books were re-catalogued and some re-classified with Barnsley shelf marks. They remained in the Musgrave family for generations, before a large portion was sold off in 1920. So, the key to finding a book from Newton’s library is to find one with James Musgrave’s bookplate covering that of the Fleet Prison warden’s son.

We cannot claim the credit for uncovering Newton’s copy of his Opticks in its second edition, but we relished selling it this year. We noticed it had the earlier state title page, dated 1717 (not 1718, as most copies have), and the first leaf of the first preface is a cancel, to correct a note about the source of part of the contents. This leaf alone was not edged in gilt, and we speculated Newton had the corrected leaf sent to him after the book had been bound. The binding was contemporary dark blue morocco gilt, smart enough to be intended for a presentation that was never made, or perhaps simply for Newton to keep himself.

Books from Newton’s library turn up from time to time, though Newton rarely annotated them, simply turning down page-corners to mark interesting passages. But a book of his own composition from his own library is a rare bird indeed.