Collecting Mary Shelley

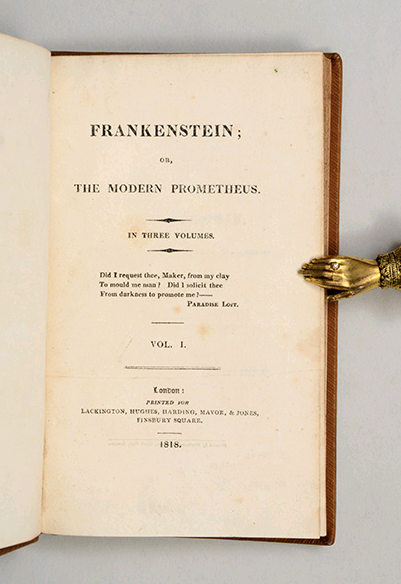

Some might think collecting Mary Shelley books a daunting task. The first edition of her most important and well-known book, Frankenstein(1818), is rare and so valuable as to be out of the reach of many collectors. However, there are many other opportunities to collect her published works.

Frankenstein was almost immediately popular with the public. In 1823 the novel was turned into a stage melodrama by Richard Brinsley Peake. Presumption, or, The Fate of Frankenstein was performed at the English Opera House, a production attended by Mary and her father William Godwin. Playbills from this and other popular early productions are attractive ephemera for collectors of Mary Shelley’s books.

Partly as a result of the success of the play, Godwin arranged a second edition of Frankenstein (1823), the first to name Mary Shelley as author. As Mary was living in Italy, Godwin made the textual amendments himself, though Mary accepted those and used it as the basis for her extensively revised third edition of 1831.

The third edition has the important new preface, in which Mary gives a full account of the tale’s genesis in the famous storytelling competition with Byron and Polidori at the Villa Diodati, and a vivid frontispiece. It was published as one of Richard Bentley’s Standard Novels, two years ahead of his Jane Austen editions in the same series.

Frankenstein was reprinted several times throughout the 19th century, but a major boost to its persistence in popular culture was the 1931 film version directed by James Whale, and starring Boris Karloff as the creature. Karloff’s memorable portrayal is captured in book form in the photoplay edition issued in 1931. An American illustrated edition in more sophisticated vein features the powerfully dramatic wood engravings of Lynd Ward (1934).

Frankenstein was not Mary Shelley’s only pioneering work in the science fiction genre. Her novel The Last Man (1826) is set in the 21st century, when a cataclysmic plague seemingly destroys every person on earth except the narrator of the novel.

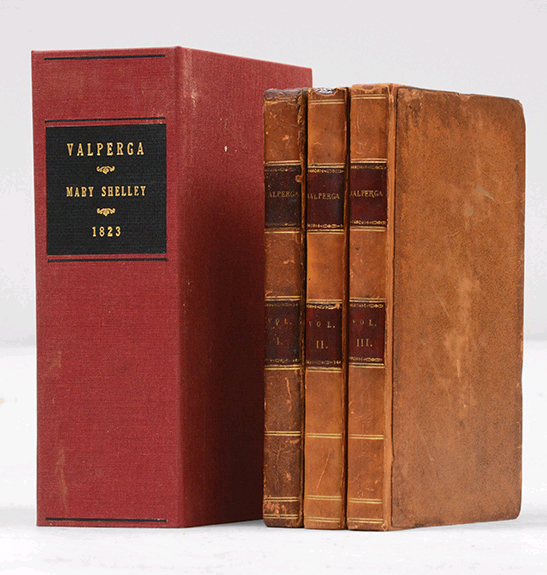

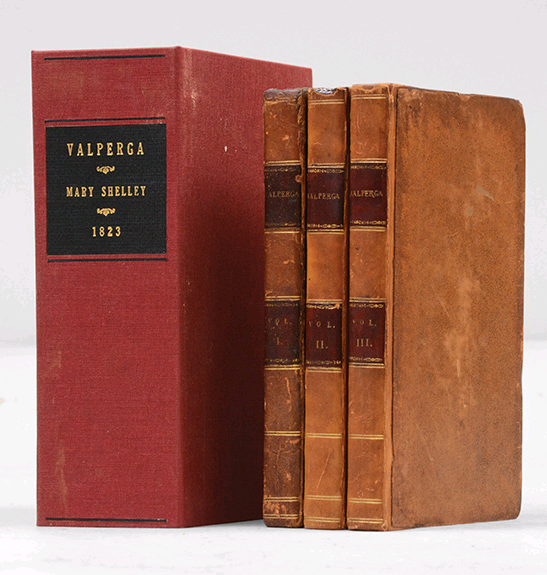

Valperga, or, The Life and Death of Castruccio Castracani (1823) and The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck (1830) are both historical novels, set in 14th-century Italy and 15th-century English respectively.

Lodore (1835), her fifth novel, and Falkner (1837), her sixth and final novel, shift away from supernatural or historical settings to contemporary stories offering critiques of the limitations of the conventional Victorian class and legal systems. These are both worthy titles for anyone interested in collecting Mary Shelley books that may not be apparent to the layperson.

Lodore is probably the novel in which Mary Shelley gives her least disguised portrait of Byron, though Raymond in The Last Man was also clearly modelled on him. Claire Clairmont, Mary’s stepsister and Byron’s discarded lover, believed that Byron’s “vile spirit” haunted all her novels.

Mary Shelley’s literary career is of course inextricably linked with that of her husband, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Her first book is primarily her revision of their elopement journal, along with some added material including P. B. Shelley’s poem “Mont Blanc”, published anonymously as History of a Six Weeks’ Tour of France, Switzerland, and Germany (1817).

After his death, her carefully edited collection, The Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley (4 vols, 1839), includes her annotations that place his works within their historical context. Her edition is regarded as a turning point in the acceptance of P. B. Shelley as a major author.

Mary also published several dozen reviews, short-stories, and poems in prominent London journals and the then popular annuals, such as The Keepsake.

Recent Comments