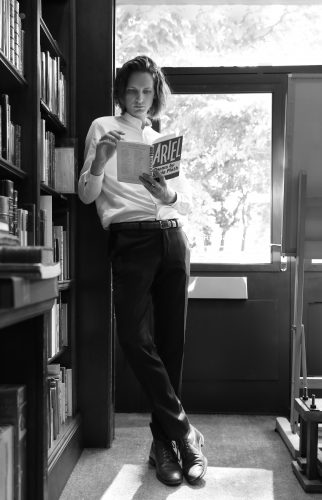

Pauline Schol

What does a normal day look like for you at Peter Harrington?

I am the shop manager of our Mayfair premises. My days are actually very varied. Besides assisting customers both in the shop and via telephone, I make sure the shops runs smoothly. This entails everything from keeping on top of our stock in the shop and making sure the shelves are stocked with new and interesting books, liaising with my colleagues in the Fulham Road premises about books that need to be shipped, books that need to be gathered for new catalogues or for book fairs, as well as addressing customer inquiries. I also ensure that our displays are looking beautiful and that the whole space is tidy.

Some of my more “behind-the-scenes” jobs include taking care of our service contracts (such as with our security provider), ordering supplies, planning staff schedules, liaising with the landlords, and generally keeping everything running smoothly. I also support our marketing and events team when hosting events here in the shop.

And what might an extraordinary day look like?

Any day can take you by surprise. We often collaborate with dealers and galleries in the neighbourhood and, one day, I got a phone call from one saying they’d be opening their doors sooner than expected after the lockdown and needed to install an exhibition of fine bindings by the next day. I created a list of books, gathered them from our shops in Chelsea and Mayfair, organised transport to the venue and put the exhibition together all within 24 hours.

In a less glamourous contrast, I recently walked into the shop to find we had a leak coming from the property above. Water damage is one of the worst things that can happen to books, so obviously this needed my immediate attention!

What was your journey into the rare book trade?

When I finished my undergraduate degree in literature and linguistics in the Netherlands, I had no clue where to go from there. I had always wanted to move abroad and, after a year off working in an archive, I eventually settled on the Master’s Degree in the History of the Book at London’s Institute of English Studies. As the course drew to an end, I still wasn’t any clearer about what my future would look like. One day, our course tutor announced that they wanted to trial a bookselling internship and I signed up. “A bit of work experience wouldn’t hurt,” I thought!

As it turned out, I absolutely loved my internship with Ash Rare Books and decided to see if I could make a

career out of this. I attended the York Antiquarian Book Seminar (YABS), a three-day intensive course where you learn all about what it entails to work in the rare book trade. When I got back to London I printed off about 50 copies of my CV and went on a tour of London’s rare bookshops. When I walked into Peter Harrington to give them my CV, I was greeted by someone I had met at YABS. A few days later I was asked if I would like to come for an interview.

What are some of the key learnings you took from your Book History degree?

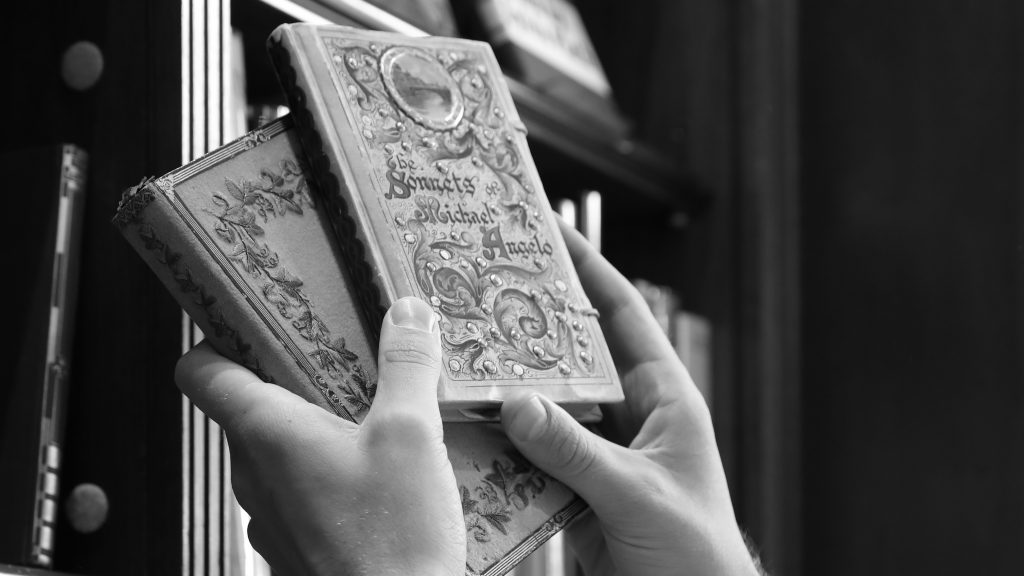

The course has a very hands-on approach and focuses on the material aspect of books. It instilled in me the importance that books are meant to be handled. My colleagues at Peter Harrington share this belief and we encourage visitors to our shops to take the books off the shelves and handle them.

You had lots of interesting professional experience before joining Peter Harrington. Can you tell us a little about how you found some of these roles and what you did there?

You had lots of interesting professional experience before joining Peter Harrington. Can you tell us a little about how you found some of these roles and what you did there?

Before moving to the UK and starting my MA I spent a year working at an archive where I worked on a digitisation project. This particular archive houses one of the most complete slave trade archives in the world and has been given UNESCO status. I helped translate transcriptions from 18th century Dutch to English, as well as do background research (https://eenigheid.slavenhandelmcc.nl/introductie-en/?lang=en). This was where I discovered my passion for handling original materials, which led me to apply for the MA History of the Book.

During my Master’s, I did the aforementioned internship with Ash Rare Books. I learned so much from

Laurence Worms, the owner, who taught me how to collate and catalogue books, database and website management, photography and anything else to do with running a bookshop. He also took me to my very first book fair and my first ever auction.

I also had two photography jobs at archives during my postgraduate degree. For one, I helped a university professor who didn’t live in the UK with research for his new book; I visited archives on his behalf and took photographs of the materials he needed. For the other, I took photographs at the National Archive for a big project called A Publishing and Communications History of the Ministry of Information, 1939-46 (http://www.moidigital.ac.uk/), which was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. I was given the first opportunity after being put in touch with the professor by a university classmate; for the second, it was my dissertation supervisor, a member of the Ministry of Information team, who approached me.

What are your top-three pieces of advice to anyone wanting to forge a career in the antiquarian book trade?

I would highly recommend taking a course in rare books. The Institute of English Studies Master’s course I did is available part time and perfectly geared towards working people. However, if you can’t commit to such a long course, the institute also offers summer courses, and the York Antiquarian Book Seminar is an excellent introduction to the trade, too. Besides learning more about rare books, these courses are great ways to meet like-minded people, discover job opportunities, and your teachers will often be established booksellers.

This leads to my second recommendation: get to know people who work in the trade. This has helped me with my career tremendously. I found most of my jobs or internships through word of mouth. I often hear people say the rare book trade can be a bit intimidating at first – and it was for me, too – but we really are a lovely bunch and are always happy to help out. So go to the book fairs, go to talks, or just pop into a shop like ours and talk to the staff about your interests.

And lastly, don’t give up. Ours is a relatively small trade, people tend to stay in their roles for a long time and there aren’t always many jobs available. But it’s a growing trade, especially for younger people, and eventually something will come up!

If you could purchase any book in Peter Harrington’s current collection, what would it be?

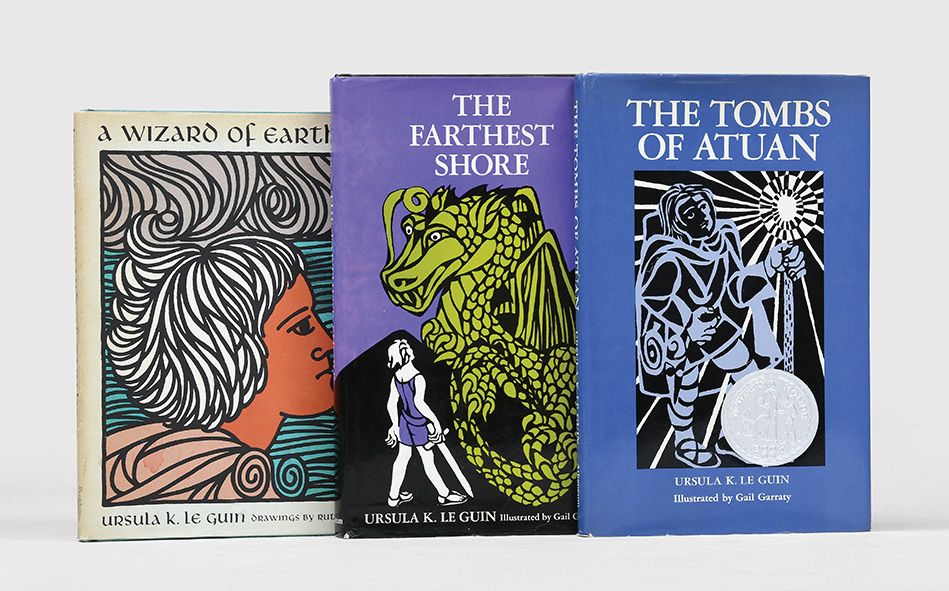

I am a big fan of fantasy and science-fiction books and absolutely love some of the dust-jacket art for these books. The Earthsea Trilogy by Ursula le Guin are books that I really enjoyed reading and I am always happy to see them on our shelves in the shop. We recently acquired this absolutely stunning US edition of William Gibson’s Neuromancer (150893), another personal favourite, and the dust-jacket is so striking. Another set of beautiful little books are the Japanese Fairy Tales by Lafcadio Hearn (149231). I find everything about this collection beautiful; the illustrations, the paper and the binding style.

I wrote my dissertation on George Orwell so seeing things like the publisher’s archive concerning the publication of Down and Out in London and Paris (131747) is also very exciting and provides a rare glimpse into the publication of such an important book. It’s a truly unique item and I wouldn’t mind owning something like that, either!

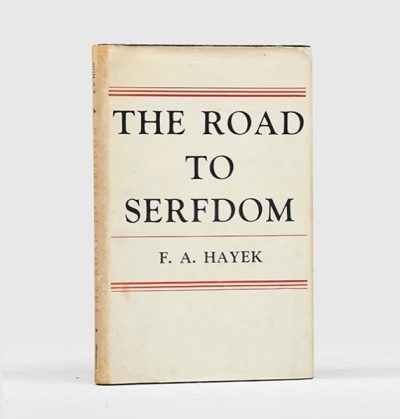

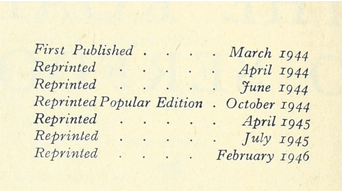

As with all books, the price for later printings falls to a fraction of the first printing. Seven impressions were published by 1946. Each is readily distinguished on the copyright page by an impression statement and date, and with an impression statement on the front flap of the jacket.

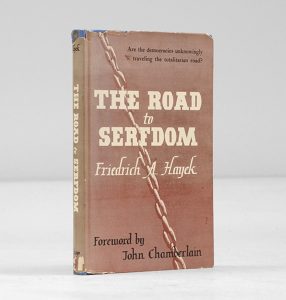

As with all books, the price for later printings falls to a fraction of the first printing. Seven impressions were published by 1946. Each is readily distinguished on the copyright page by an impression statement and date, and with an impression statement on the front flap of the jacket. Especially given the influence of Hayek in America, the first American edition (which was also the first foreign edition) is highly collectible. The first printing was published by the University of Chicago in September 1944, and is again distinguished by the same absence of later printing statements on the copyright page and jacket. John Chamberlain contributed a new preface for the edition. The jacket bears a striking chain design, and as with the first British edition is difficult to find, more difficult still in nice condition.

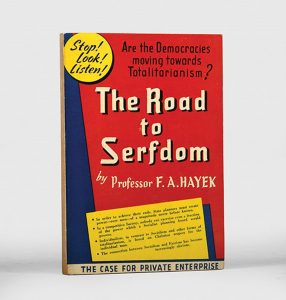

Especially given the influence of Hayek in America, the first American edition (which was also the first foreign edition) is highly collectible. The first printing was published by the University of Chicago in September 1944, and is again distinguished by the same absence of later printing statements on the copyright page and jacket. John Chamberlain contributed a new preface for the edition. The jacket bears a striking chain design, and as with the first British edition is difficult to find, more difficult still in nice condition. Early foreign editions of the text, including the first appearances in each foreign language, represent a broad collecting avenue. The most striking of the early foreign editions was the first Australian paperback edition in 1945, with garish red, blue, and yellow wrappers proclaiming: “Stop! Look! Listen! Are the Democracies Moving Towards Totalitarianism?”. The contrast between this design, and that of the plain jacket of the original British first edition, could not be more conspicuous.

Early foreign editions of the text, including the first appearances in each foreign language, represent a broad collecting avenue. The most striking of the early foreign editions was the first Australian paperback edition in 1945, with garish red, blue, and yellow wrappers proclaiming: “Stop! Look! Listen! Are the Democracies Moving Towards Totalitarianism?”. The contrast between this design, and that of the plain jacket of the original British first edition, could not be more conspicuous.

Recent Comments