Printing and the Mind of (Wo)man

The historic catalogue Printing and the Mind of Man, or PMM as it is usually abbreviated, was first published in 1967. Its origins lie in two exhibitions: the first, held at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge in 1940, and the second, held at IPEX in London in 1963. The aim of both, to differing degrees, was to examine the impact of printing technology and printed books on the development of Western civilization.1 The resulting catalogue soon became an important reference work for booksellers, librarians, and bibliophiles alike. It remains an indispensable resource and is itself a collectible.

It is just over sixty years since the 1963 exhibition, which gives us and many others a timely opportunity to reflect on its significance. In their introduction to PMM, the compilers, John Carter and Percy Muir, took care to define the parameters of their ambitious project. “Our task has necessarily been that of exclusion rather than inclusion, and no doubt each reader will make his own list of deplorable omissions”.2

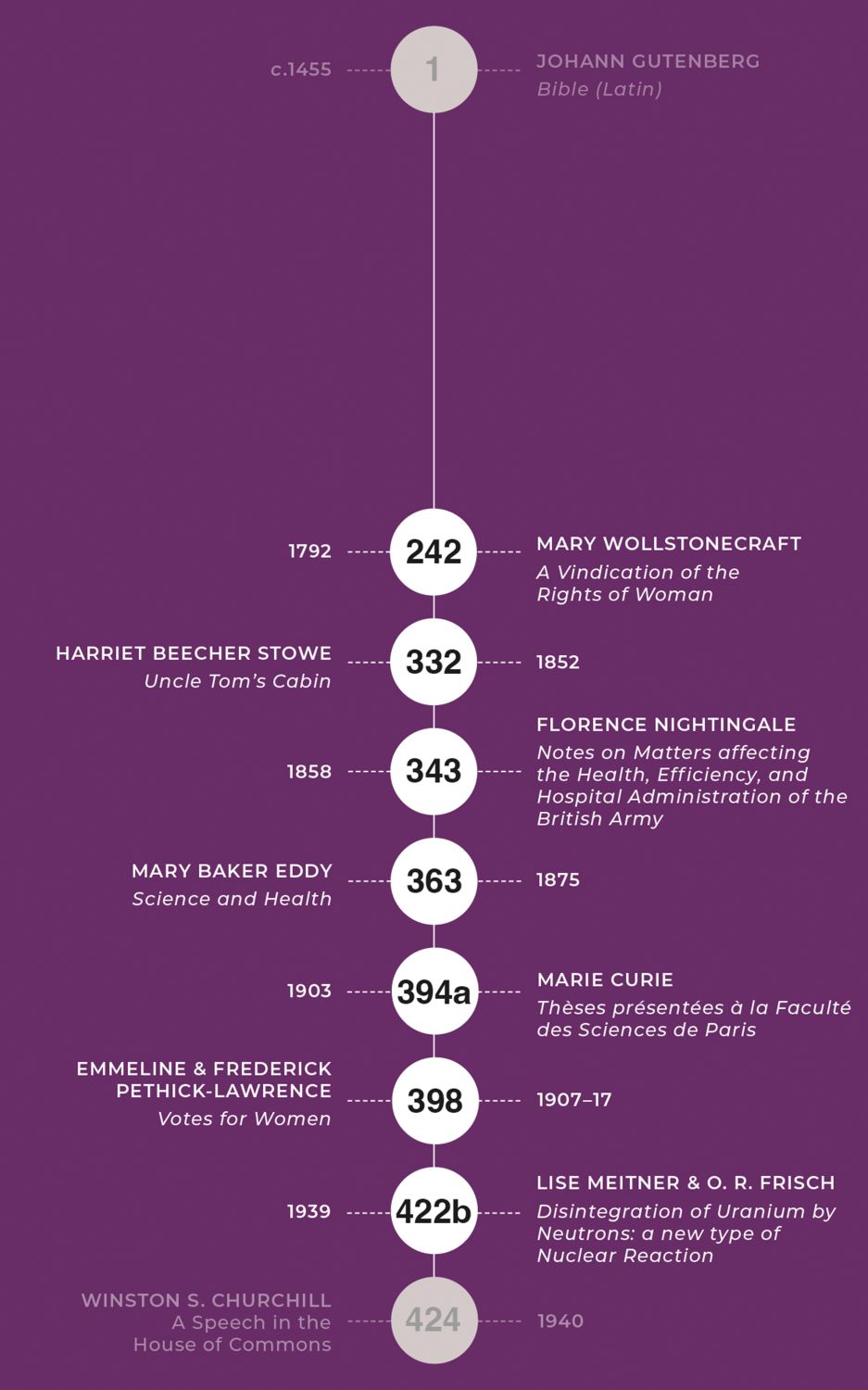

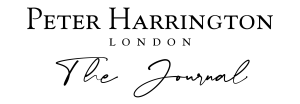

The almost total omission of women from PMM is a topic that interests us, both professionally and personally. Of the 424 works selected for inclusion, only seven are credited to women – to Mary Wollstonecraft, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Florence Nightingale, Mary Baker Eddy, Marie Curie, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, and Lise Meitner.

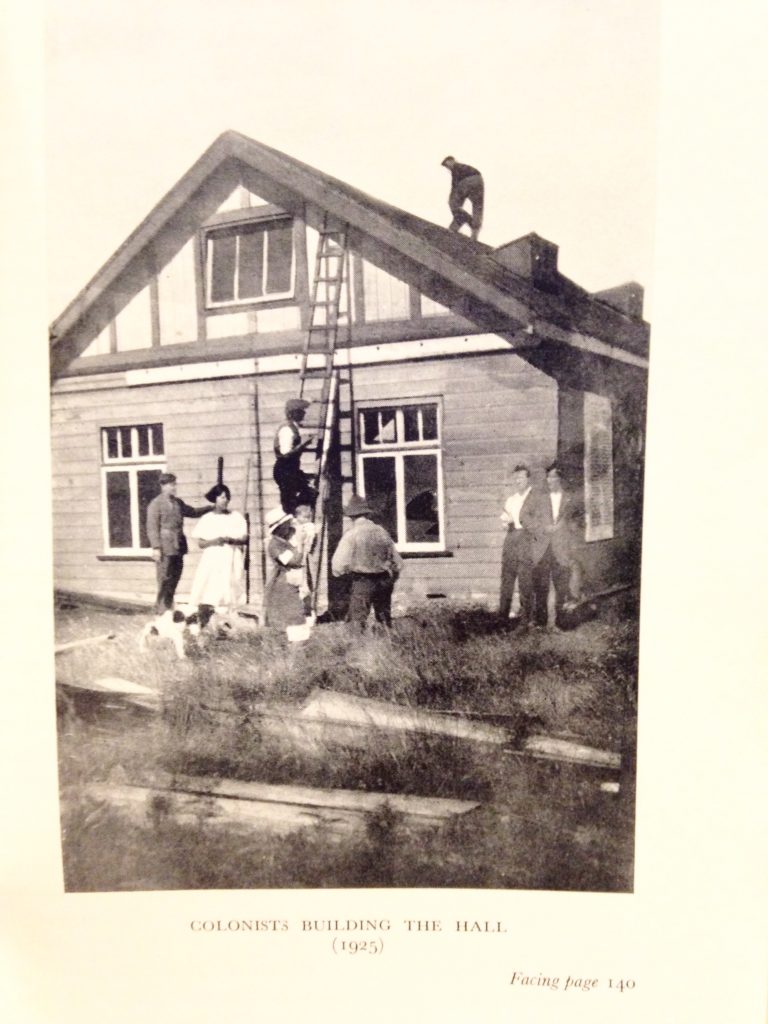

Between Gutenberg and Churchill: the seven women of PMM (© Peter Harrington)

While the reasons for this are multi-faceted, it is nevertheless a tiny fraction of the whole: 1.6%. Women were present in the technical and intellectual history of print from its earliest days, working not only as writers, but also as printers and press owners. Many valuable conversations have redressed the gender imbalance in PMM. Miranda Garno Rossa’s article on Elizabeth Holt, who printed John Locke’s Essay Concerning Humane Understanding (PMM #164), encourages readers to “recognize diversity both without and within” the catalogue.3

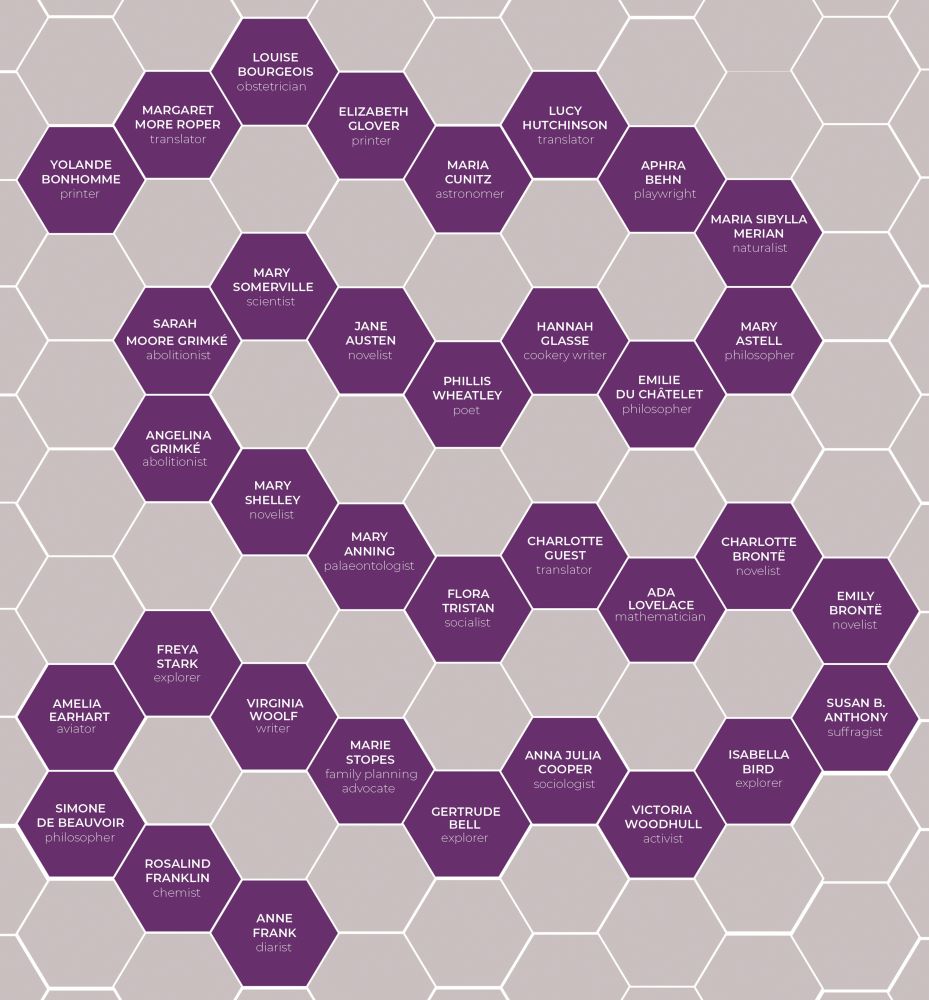

What follows is our assessment of the representation of women within PMM. In some cases, we suggest the revision of certain entries to reflect women’s involvement more accurately. In others, we propose landmark texts by female authors which we feel were overlooked.

Many women are rendered invisible, in part due to the “Matilda Effect”, and several entries could be lightly amended with this in mind.4 Antoine Laurent Lavoisier “accomplished a chemical revolution” with his Traité Élémentaire de Chimie (#238): the essential role played by his wife Marie-Ann Paulze in its creation should be noted.

The entry for Lewis and Clark’s expedition (#272) would today be re-written to acknowledge the importance of their guide and interpreter Sacagawea. The heading for the Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei (#326) silently attributes “Workers of the World, Unite!” to Marx and Engels. However, the slogan was coined by Flora Tristan in her Union ouvrière (1843) five years before the Manifesto was published. Harriet Taylor Mill is the unnamed “wife” of John Stuart Mill in On Liberty (#345) – a conspicuous omission, given that, in his words, On Liberty “was more directly and literally our joint production than anything else which bears my name”.

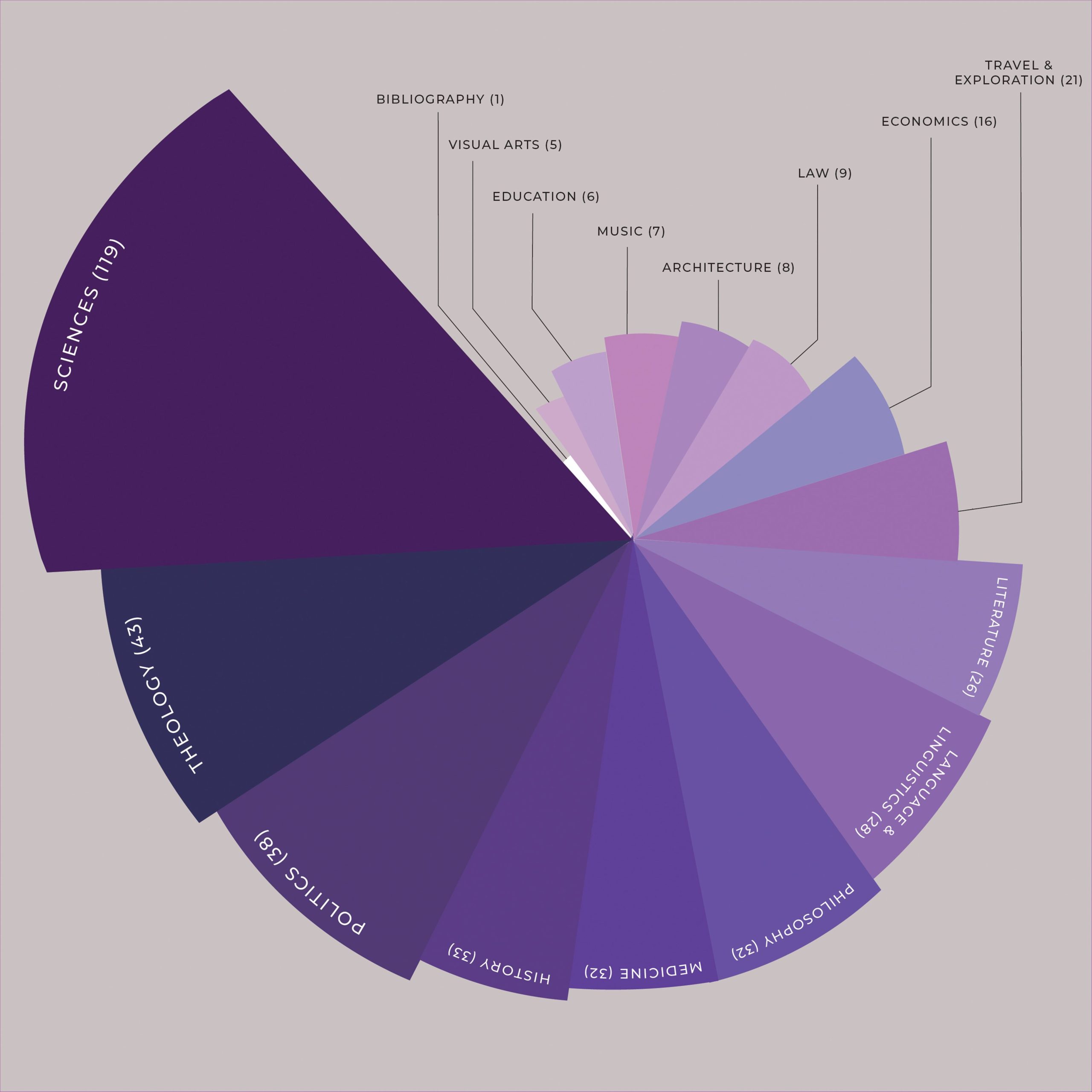

In approaching this topic, we reviewed the subject composition of the first edition of PMM; the diagram below visualizes the results.

PMM has a strong focus on the sciences, and three women are found in this category: Nightingale, Curie, and Meitner. There are numerous women whose inclusion would profitably broaden the horizons of this sector of PMM. “The Foundation of Obstetrics as a Science” would be an appropriate heading for midwife Louise Bourgeois’s pioneering work of 1609, Observations diverses sur la sterilité. The first edition of Urania Propitia (1650), a simplification of Kepler’s Rudolphine Tables by Maria Cunitz, provided a parallel Latin–German text which helped establish the latter as a leading scientific language. This typographic choice is precisely the kind of detail that dovetails nicely with PMM’s interest in book production. Mary Anning’s paleontological discoveries brought about a crucial shift in our understanding of the Earth’s geological history; she never published articles under her name, so we can only propose a letter she wrote to the editor of the Magazine of Natural History, an extract of which was published in 1839. Maria Montessori’s educational techniques were among the first to be marketed as empirically grounded; the first edition of her 1909 work, Il metodo della pedagogia scientifica…, sold over 5,000 copies in the first week and changed the course of teaching.

PMM cannot have foreseen those texts significant to the nascent digital revolution, but it does feature a few key works which illustrate early technological developments. The committee considered, but decided against, including an article on Charles Babbage’s Calculating Engine in the 1963 exhibition. It was around this time that Ada Lovelace’s contributions to computer science were beginning to be recognized; her Sketch of the Analytical Engine (1843) is a strong contender. 5

Marie Stopes’s Married Love (1918), which was similarly discussed and dismissed, is deserving of a place: by 1935 it had already appeared in shortlists of influential books ahead of Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams (#389), Einstein’s Relativity (#408), and Keynes’s Economic Consequences of the Peace. 6 While the 1953 DNA papers of Rosalind Franklin, Maurice Wilkins, Francis Crick, and James Watson did not feature in PMM proper, those by Crick and Watson were included in the Printing and the Mind of Man auction at Christie’s London, 20 October 1999 (lots 88 and 89). Franklin and Wilkins were not represented, despite their crucial contributions to the discovery.

“An idea built the wall of separation between the sexes, and an idea will crumble it to dust” – Sarah Moore Grimké, “Education of Women”

When it comes to women’s rights, PMM connects two fulcrums of English feminist philosophy, Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman (#242) and the Pethick-Lawrences’ Votes for Women (#398) as the representative text of the suffrage movement. Works by their American counterparts, such as Victoria Woodhull’s The Origin, Tendencies, and Principles of Government (1871), Anna Julia Cooper’s A Voice from the South (1892), and Susan B. Anthony’s History of Woman Suffrage (1881–1922) would offer a welcome complement. Earlier works like Mary Astell’s radical treatises on education and marriage (A Serious Proposal to the Ladies, 1694 & 1697, and Some Reflections upon Marriage, 1700), which predate Wollstonecraft by almost a century, and later second-wave classics like Simone de Beauvoir’s Le Deuxième Sexe (1949), would bring to life this narrative of progress.

One reason why so many of these political and philosophical figures are overlooked is that PMM tends to subscribe to the so-called “great man theory” of history. Its coverage of the Second World War, for example, includes Adolph Hitler’s Mein Kampf (#415), and, while the entry condemns the dictator’s grand narrative, there is no counterpoint in the catalogue to it. The Origins of Totalitarianism by Hannah Arendt (1951), one of the most astute critiques of fascism ever written, might have fulfilled this role. Given that the origins of PMM itself lay in wartime – its earliest iteration, in 1940, opened as an exhibition to issue “a challenge to the forces of destruction” 7 – incorporating Het Achterhuis (1947) by Anne Frank would have focused attention on the catastrophic effects on the lives of Jewish people, rather than the fascist leader’s defence of antisemitism.

“That Keats and Shelley stuff”

The committee were particularly selective when it came to works of “imaginative literature”, due in large part to Stanley Morison’s dislike of “that Keats and Shelley stuff”. To forestall inevitable criticism, Carter and Muir set out a disclaimer that works of creative literature were restricted, “with a few exceptions, to the propagation of ideas (e.g. Candide, Alice in Wonderland) or characters (e.g. Hamlet or Faust) which have sensibly affected his thinking and thence his actions” – it was not enough for literature to simply inspire “the spirit of man” (PMM, p. xi).

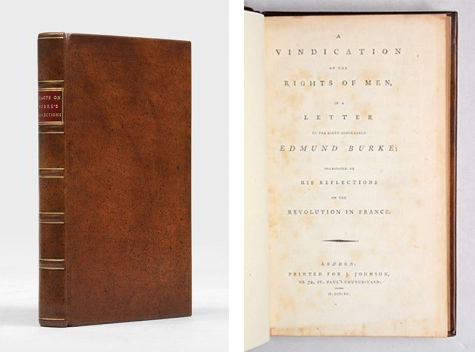

However, this had unintended effects on gender representation within PMM. Literature is a field that has had fewer barriers to entry for women than science, philosophy, or politics – subjects towards which PMM is heavily weighted. Of the 26 works of creative literature which made the final selection, one was written by a woman – Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe (#332), included for its social impact on the abolitionist cause. Phillis Wheatley’s Poems (1773) would likewise have satisfied the committee’s parameters: her written work helped further the cause of abolition and she was the first African American to publish a book of verse.

Other startling exclusions include Aphra Behn, whose Oroonoko (1688) has at least as strong a claim to being the first English novel as Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (#180). Behn was also the first English woman to earn a living from her pen. Virginia Woolf famously wrote in A Room of One’s Own (1929) – itself an excellent candidate for inclusion – that “all women together ought to let flowers fall upon the tomb of Aphra Behn . . . for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds”. Jane Austen received only a brief mention in the entry for Walter Scott (#273), who is credited with establishing the genre of historical fiction. None of her closest contemporaries in PMM – Scott, Wordsworth (#256), Lord Byron (#270) – come close today to the readership or impact that Austen has. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) is another conspicuous absence, not only as the catalyst of the science fiction genre but also for its prescient commentary on the consequences of scientific progress. Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights (both 1847), the masterpieces of Charlotte and Emily Brontë, redefined the novel and are equally eligible candidates.

Translations hold the power to transform highly specialized or otherwise broadly inaccessible texts into canonical works, and many of the earliest and most influential were produced by women. Margaret More Roper, Lucy Hutchinson, and Charlotte Guest, the translators of Erasmus (#53), Lucretius (#87), and the Mabinogion (1838–49) respectively, are three worthy contenders. 8 Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (#161) and Laplace’s Mécanique Céleste (#252) became widely read due in part to Emilie du Châtelet’s Principes mathématiques de la philosophie naturelle (1759) and Mary Somerville’s The Mechanism of the Heavens (1831). In recognition of this, Du Châtelet’s translation was sold as part of the PMM auction at Christie’s (lot 37).

“Lock up your libraries if you like; but there is no gate, no lock, no bolt that you can set upon the freedom of my mind” – Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

Although the field of travel and exploration contains many famous names, such as Hakluyt (#105), Dudley (#134), and Cook (#223), it is represented at the lower end of the scale within PMM (4.9%), receiving a similar weighting to that of literature. However, it is less surprising that no female candidate appears here; historically, the barriers to this field have been more difficult for women to surmount.

Illustrating this point, the first woman on record to have circumnavigated the globe, Jeanne Barré, who accompanied Louis Antoine de Bougainville’s 1766–69 circumnavigation, had neither the resources nor education to publish her own account. Maria Sibylla Merian, however, is a compelling candidate for inclusion. Merian travelled to Suriname without male family members at a time when it was virtually unprecedented for a woman to do so. She funded her own travels and scientific work, publishing her magnum opus Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium in 1705. Later pioneers such as Gertrude Bell, Isabella Bird, Amelia Earhart, and Freya Stark published more widely and are names with which any travel collector will be familiar.

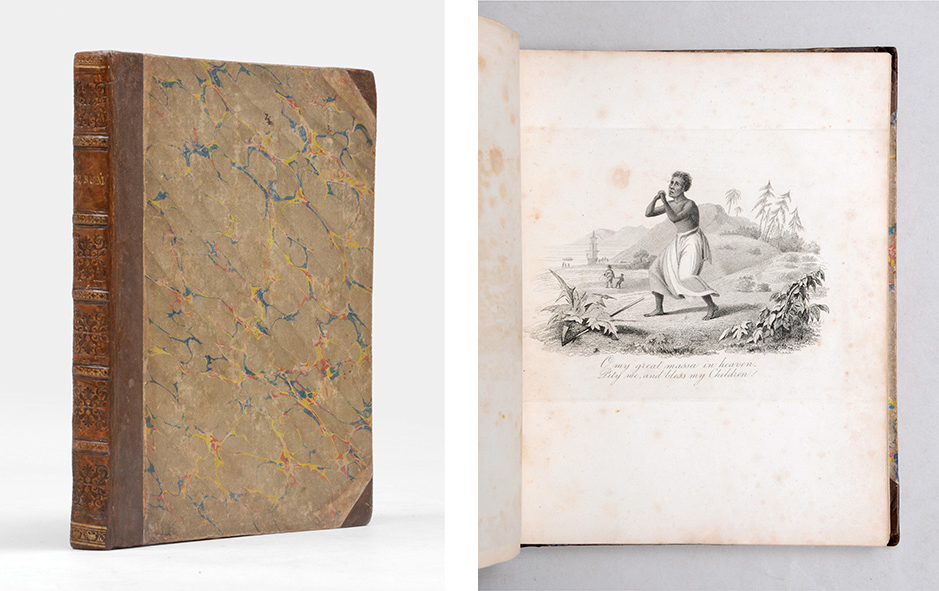

Other areas of society in which women were traditionally freer to contribute, such as cookery and music, though not explicitly commented upon by PMM’s editors, were given a low weighting in PMM or excluded entirely. Hannah Glasse’s highly influential Art of Cookery (1747), probably the best-selling non-religious title of the 18th century, is notable in this regard.

The role of women in the development of print history also merits acknowledgment. Elizabeth Holt and the other female printers in PMM, the widows of Jean Boudot and Eberhard Klett, should be joined by Yolande Bonhomme, who, in 1526, was the first woman to publish the Bible. Elizabeth Glover owned the printing press on which the Bay Psalm Book (1640), the first book printed in British North America, was set. It holds the record for the most expensive printed book ever sold at auction: Sotheby’s New York, 26 November 2013, $14,165,000.

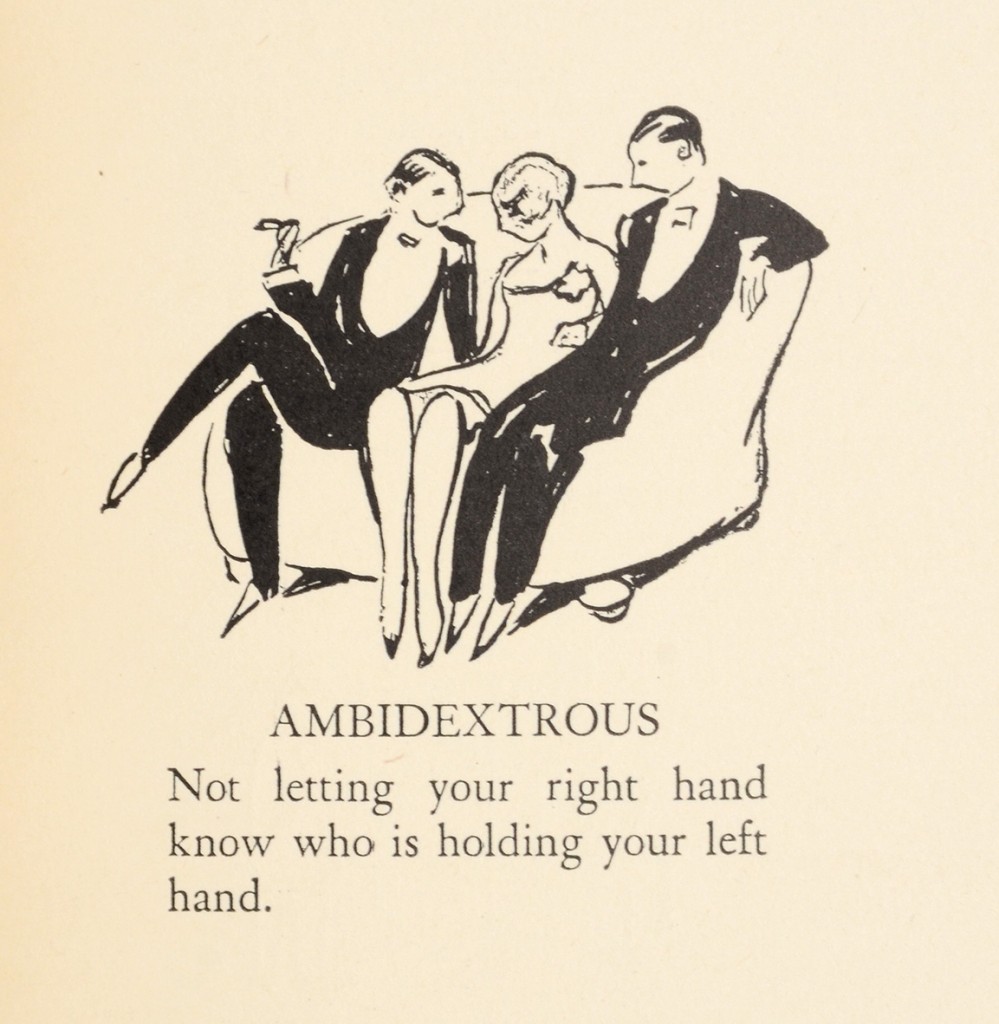

An alternative canon for women in PMM (© Peter Harrington)

“Books are not made to be believed, but to be subjected to inquiry” – Umberto Eco, The Name of The Rose

PMM remains a remarkable monument to a specific project, conceived at a specific point in history, by a specific group of people. Its omissions naturally reflect larger systemic issues of the time. Gutenberg’s status as the herald of “the first age of printing” is a Eurocentric belief tempered today by our awareness of far older Asian technologies. The abolitionist movement is traced through several entries, but none of the amplified voices belong to African Americans. There are no works by people of colour on this subject, nor on any other. To move beyond women’s writing for a moment, the addition of texts such as Ignatius Sancho’s Letters (1782) and Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life (1845) would immeasurably enhance its ethnic diversity. The addresses of Angelina and Sarah Moore Grimké (1837) would amplify these accounts further.

To echo Katy Hessel’s phrasing from her recent reappraisal of E. H. Gombrich’s Story of Art, which included no female artists until its sixteenth edition: “It’s not that I believe there to be anything inherently ‘different’ about work created by artists of any particular gender – it’s more that society and its gatekeepers have always prioritised one group in history”. 9

In 2014, Nicolas Barker said that the original committee “did not guess how much it would influence both private and institutional collecting, nor the extent to which it would increase the prices of the books, those, at least, that were accessible . . . we wondered whether posterity would reverse our verdicts, or at least see not one but conflicting views as equally significant”. 10 PMM has undoubtedly shaped the business of rare books, but it is now one of many tools used by booksellers, curators, and collectors. 11 By considering the choices made in the publication of such reference works, we simultaneously acknowledge their continued significance and advocate for a more complex and diverse version of print history and the canon.

By Theodora Robinson & Emma Walshe, with graphics by Abbie Ingleby

1. For more on the genesis of PMM, see Anna Middleton, “The Origins and Legacy of Printing and the Mind of Man“, The Book Collector, vol. 72, no. 4, Winter 2023, pp. 637–43, and the issue in its entirety.

2. In a recent article on the papers of Percy Muir, Sandy Malcolm notes that “only three out of the 315 works considered , i.e. less than 1 percent, were by women” (p. 649). Of these three, one made it into the final catalogue: Curie on radium. The other two, Elinor Glyn’s Three Weeks (1907) and Marie Stopes’s Married Love (1918), were dismissed. See Malcolm, “The Percy Muir Archive: Titles Rejected for PMM”, pp. 645–53; see footnote 1.

3. Miranda Garno Nesler, “Elizabeth Holt and the Early Modern Women Imprinting the Mind of Man”, in Cathleen Baker & Rebecca M. Chung, eds, Making Impressions: Women in Printing and Publishing, Ann Arbor: The Legacy Press, 2000, p. 79.

4. This bias phenomenon was first described by Matilda Joslyn Gage in her essay “Woman as Inventor” (1870). The term itself was coined by Margaret W. Rossiter in “The Matthew Matilda Effect in Science”, Social Studies of Science 23, no. 2, 1993, pp. 325–41.

5. For further details on PMM and Babbage, see Malcolm, pp. 650–1.

6. Edward Weeks, This Trade of Writing, Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1935, p. 276.

7. Brooke Crutchley quoted by Middleton, ibid., p. 638.

8. Margaret More Roper, trans., A devout treatise upon the Pater Noster, 1525; Lucy Hutchinson, trans., English translation of De rerum natura, circulated in manuscript c.1650s but not published until 1996; Charlotte Guest, trans., The Mabinogion from the Llyfr Coch o Hergest, and other ancient Welsh manuscripts, 1838–49.

9. Katy Hessel, The Story of Art Without Men, London: Hutchinson Heinemann, 2022, p. 11.

10. “Fifty Years On: The Book Collector and ‘Printing and the Mind of Man’”: a talk delivered by Nicolas Barker to the University of Otago Centre for the Book on 29 May 2014.

11. See Rebecca Romney, “On Feminist Practice in the Rare Books and Manuscripts Trade: Buying, Cataloguing, and Selling”, Criticism, vol. 64, issue 3, article 13, 2022.

Recent Comments